What is cycling without its climbs? Between the famous climbs of the Alps, the Dolomites and the Pyrenees to the joy of racing up your local butte, climbing is the tie that binds all the disparate threads of cycling together.

Europe is home to some of the most legendary climbs, with the Grand Tours providing the mystique around the likes of the Alpe d'Huez, Passo del Stelvio, Col du Tourmalet and Alto de Angliru. Even if you were to look beyond those names, during the last week of the Tour de France, there were climbs that garnered more attention than any American climb will ever receive from the larger cycling consciousness.

Nevertheless, the United States has plenty of towering monsters with its own mythology, albeit with less fanfare than its European cousins. Names like Flagstaff, Logan Pass, Haleakala, Gibraltar and Mount Baldy stand out amongst the crowd as famous climbs stateside.

Yet there are a handful of giants that are well below the radar in the United States that are worthy of celebration and even warrant a trip. After years of travelling the U.S. and taking time to find the lesser-ridden climbs, here are four lesser-travelled monster climbs that you should add to your bucket list.

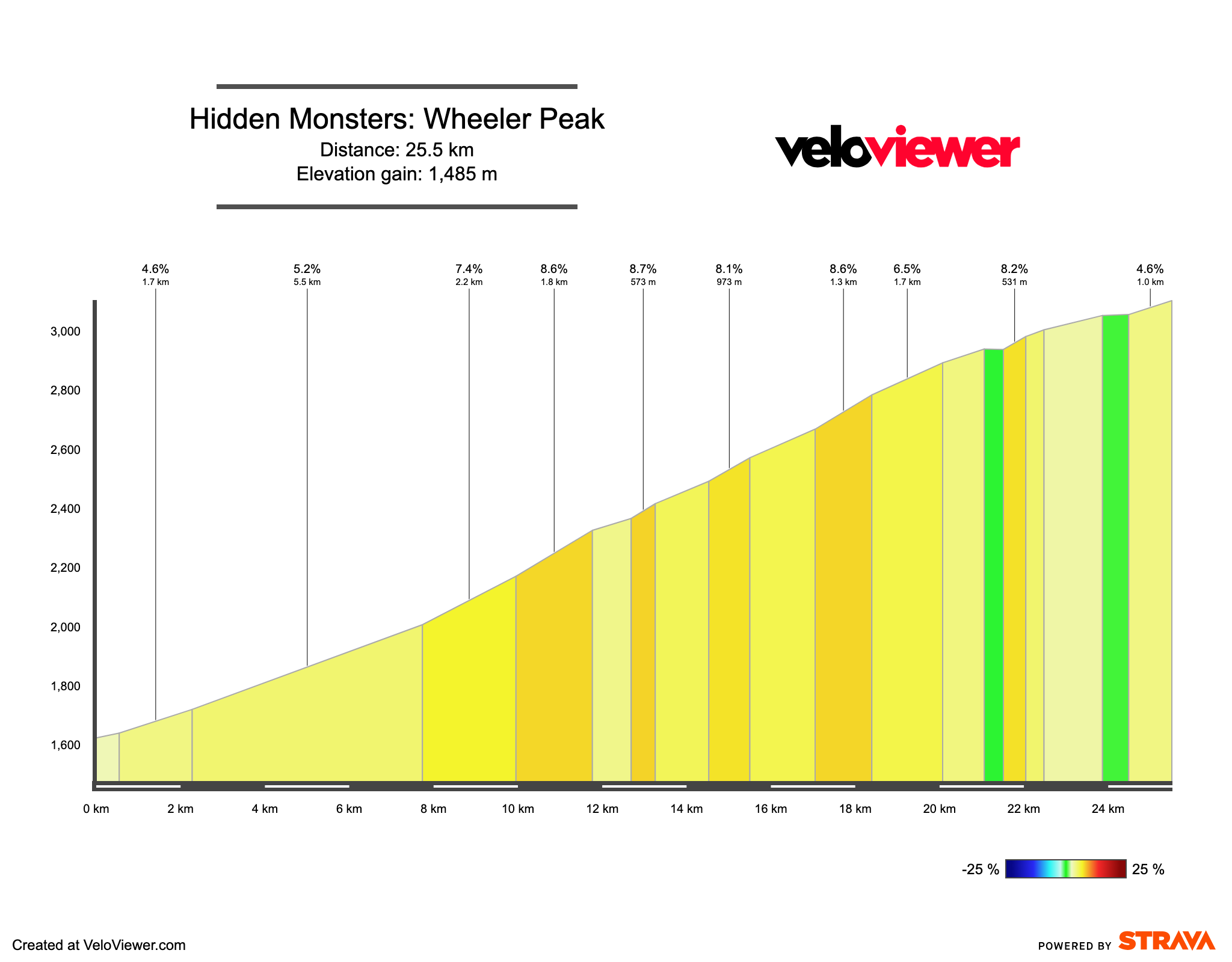

Wheeler Peak – Great Basin National Park, Nevada

25.5 km (15.8 miles), 5.7%, 1,485 metres (4,872 feet)

Strava link

Men’s KOM: Levi Leipheimer – 1:19:39

Women’s KOM: Stephanie Bissonnette – 1:40:19

Nevada is probably not the first American state that comes to mind when one thinks of the great American mountains. Nevertheless, the state is statistically speaking the most mountainous state in the whole country. While most of this terrain is marooned far from any road, the highest of Nevada’s peaks has a road that twists its way just a couple of thousand feet shy of the 13,000-foot summit.

Wheeler Peak sits close to the eastern border of Nevada and is the centerpiece of Great Basin National Park. Rising out of the bare high desert of America’s Great Basin, Wheeler Peak tops out at 3,982 meters and holds Nevada’s only permanent glacier. Along the way to the trailhead to the summit at 3,060 meters the Wheeler Peak access road climbs through layers of ecology – from sagebrush to gnarled juniper trees, and finally to rich aspen groves as the altitude ticks up.

The climb itself is a beast. Unlike the gradual climb of Rainier, Wheeler Peak is steep throughout, consistently hitting slopes of over 6% with slow chip-sealed pavement making the going all the more punishing. Crucially, the climb is also at a significant altitude, with the start of the climb sitting at 5,500 feet. The scenery takes a back seat at the start of ther effort with the first few miles taking a dead straight path through the sagebrush desert of the base of the climb. It seems neverending and punishing as there are few reference points to give a rider any sense of progress. It is a tough start, but one that eventually offers a brilliant contrast to the excitement of the forests and switchbacks that follow on the second half of the climbs.

What’s more, once at the top of the climbing, there's always the option to extend the effort by strapping on some hiking shoes and trekking the rest of the four miles to the summit by foot to make the full 2,357 metres of ascents under human power.

Regardless of where you decide to end your day, Wheeler Peak is a climb difficult enough to make for a challenge for any rider, while also offering a glimpse at a natural landscape that is hard to find in such a condensed form anywhere else in the United States. It is a unique mountain climb that delivers a fascinating look at one of America’s truly hidden natural gems.

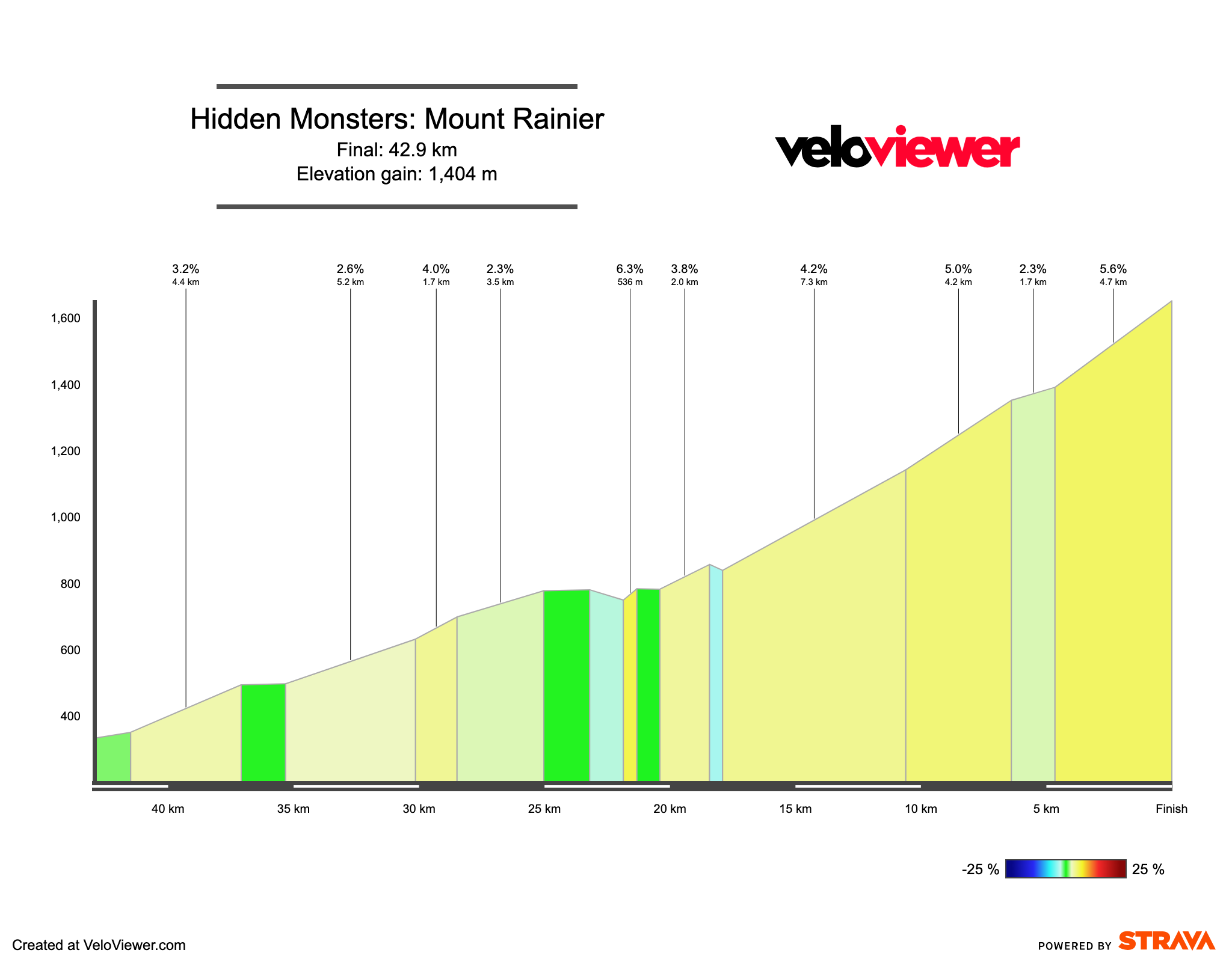

Paradise, the backway – Mount Rainier, Washington

42.9 km (26.7 miles), 3.2% average, 1,404 metres (4,606 feet)

Strava link

Men’s KOM: Logan Jones-Wilkins – 1:42:22

Women’s KOM: N/A

Washington is chock full of amazing climbs. With rich forest and copious mountainous terrain split between the Cascade mountains and the Olympic range, there is ample opportunity to test your climbing legs at the top of the Pacific Northwest.

In the heart of the state, Mount Rainier is the grandest of all of these mountains, rising up from a low altitude to a towering height of 4,392 metres. No roads go to the top, with the summit surrounded by massive glaciers, but with the spectacle of the mountain drawing scores of visitors every day, pavement does reach the shoulder of the volcanic monster at the outpost called Paradise. For cyclists, in particular, the name is a fitting descriptor as the multiple routes up the mountain offer a healthy shoulder, great views and some of the best riding America has to offer.

While most American climbs have two routes up culminating in a pass, the climb to the Paradise Visitor Center in the Rainier National Park has a third backway that extends the climbing and adds time away from more heavily trafficked roads and instead towards a meandering centerline-less road cutting through a rich fern-filled forest along a glacial creek.

The climb is a gradual haul at 41.3km at 3.2% from Packwood, Washington, to Paradise. The effort starts with the easiest gradients as it follows Skate Creek up a tight wooded valley before a right turn and a quick trip up a forest service road deposits any would-be climbers into the back entrance of the Longmire Campground, which then connects to the main thoroughfare up the mountain. Once on the main road to Paradise, the climbing ramps up slightly as the road switchbacks its way through a massive rocky gully carved out by ancient glaciers on the southwestern shoulder of the volcano.

This is the point of the climb where views of the massive mountain come into focus. While mountain views are staples of most climbs, Rainier's enormity is one-of-a-kind in the United States. There is no shame in stopping along one of the road pull-offs to breathe and gaze at the mountain. Really, it would be a shame not to.

While the distance of the climb to Paradise could scare some away from the mountain, the climb is a gradual test and is a fantastic place to delve into big mountain riding. The pavement is intact as well, and if you were to make it a loop, road improvements on the eastern side of the pass have been underway over the last few years to make the passage safe. What’s more, the visitor centre at the top offers a refresher on water and restrooms, allowing cyclists to keep their loads light on the way up.

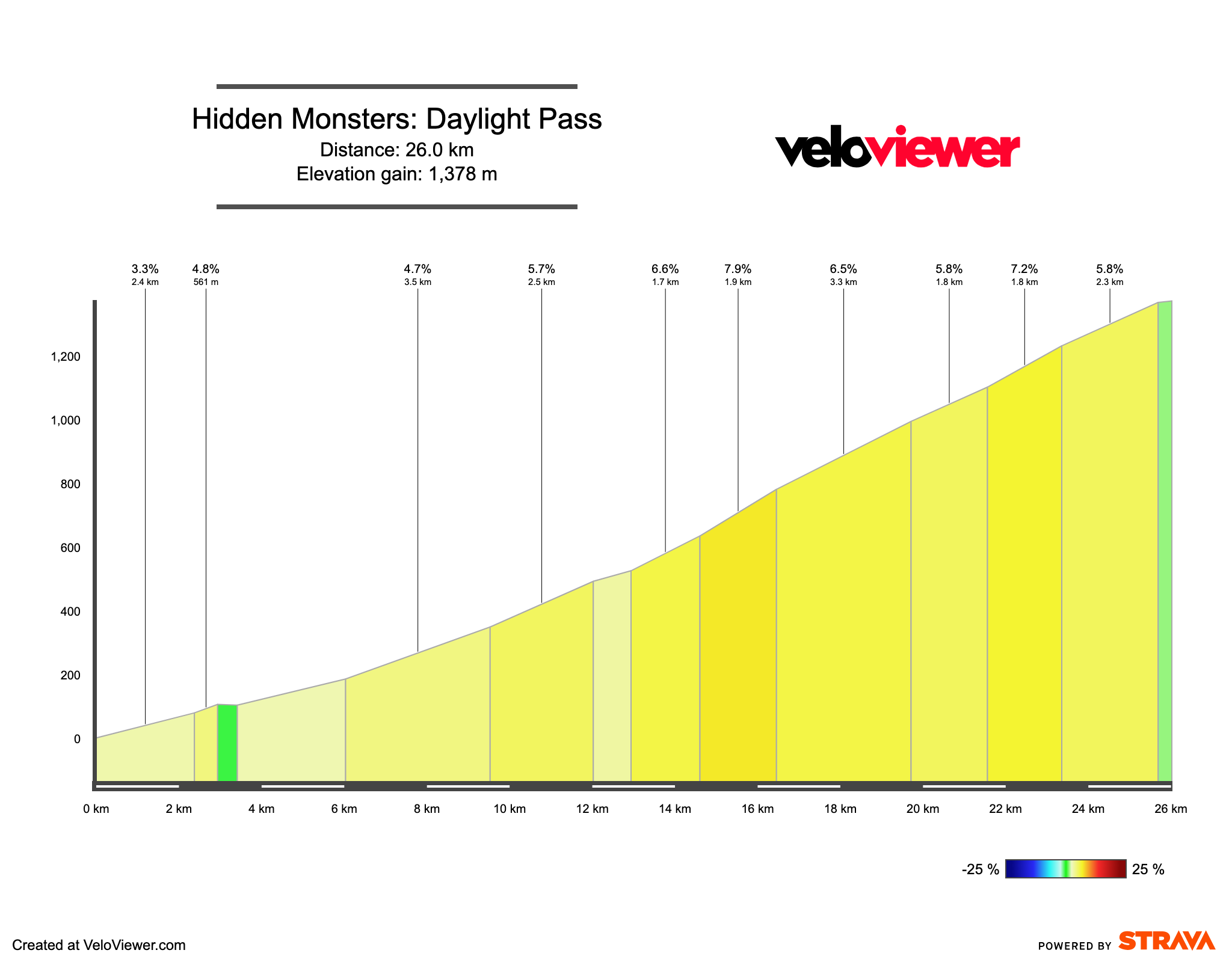

Daylight Pass – Death Valley, California

26.0 km (16.1 miles), 5.3% average, 1,378 metres (4,520 feet)

Strava link

Men’s KOM: Chris Bosco – 1:24:21

Women’s KOM: Stephanie Bissonnette – 1:31:53

The American West is notorious for its sky-high passes that scale heights far higher than roads visited in Europe. While 2,000 metres is the threshold for what is considered high-altitude ascents in France, Italy, and Spain, in the western half of the United States, the big climbs frequently exceed the 3,000-metre threshold.

Daylight Pass, however, goes to the other extreme. The pass has two different begins, but if you take the path from Furnace Creek, one of the main visitor centres, the climb begins from below sea level at Badwater Basin in Death Valley and ploughs its way up to over 1,300 meters along the eastern rim of America’s hottest valley. While the heat is what Death Valley is known for, once the climb begins it is clear to see all the other beautiful characteristics of the biggest national park in the lower 48 states.

Along the climb, the surroundings change from barren sands to high desert sagebrush, while towering rock formations spiral towards the sky along the punishing slopes. This 360-degree panorama of some of the most incredible arid terrain anywhere in the world is accessible via a great cycling route.

To make a complete loop, road bike options are a bit limited at the top of the climb, as there are no major towns within many miles of the pass. However, there are water and food options available in Betty, Nevada, a couple of miles down the main road. The best option, however, is to climb the road with a gravel bike and then extend the ride back down to Death Valley via Echo Canyon or Titus Canyon.

Titus Canyon is currently closed to all traffic, with the possibility of reopening in January 2025, but it is one of the most dramatic dirt roads in the United States. Echo Canyon is open but extremely remote and rarely travelled. Consultation with the Death Valley park authorities is greatly encouraged, as the Death Valley area is one of the most extreme and remote anywhere in the United States.

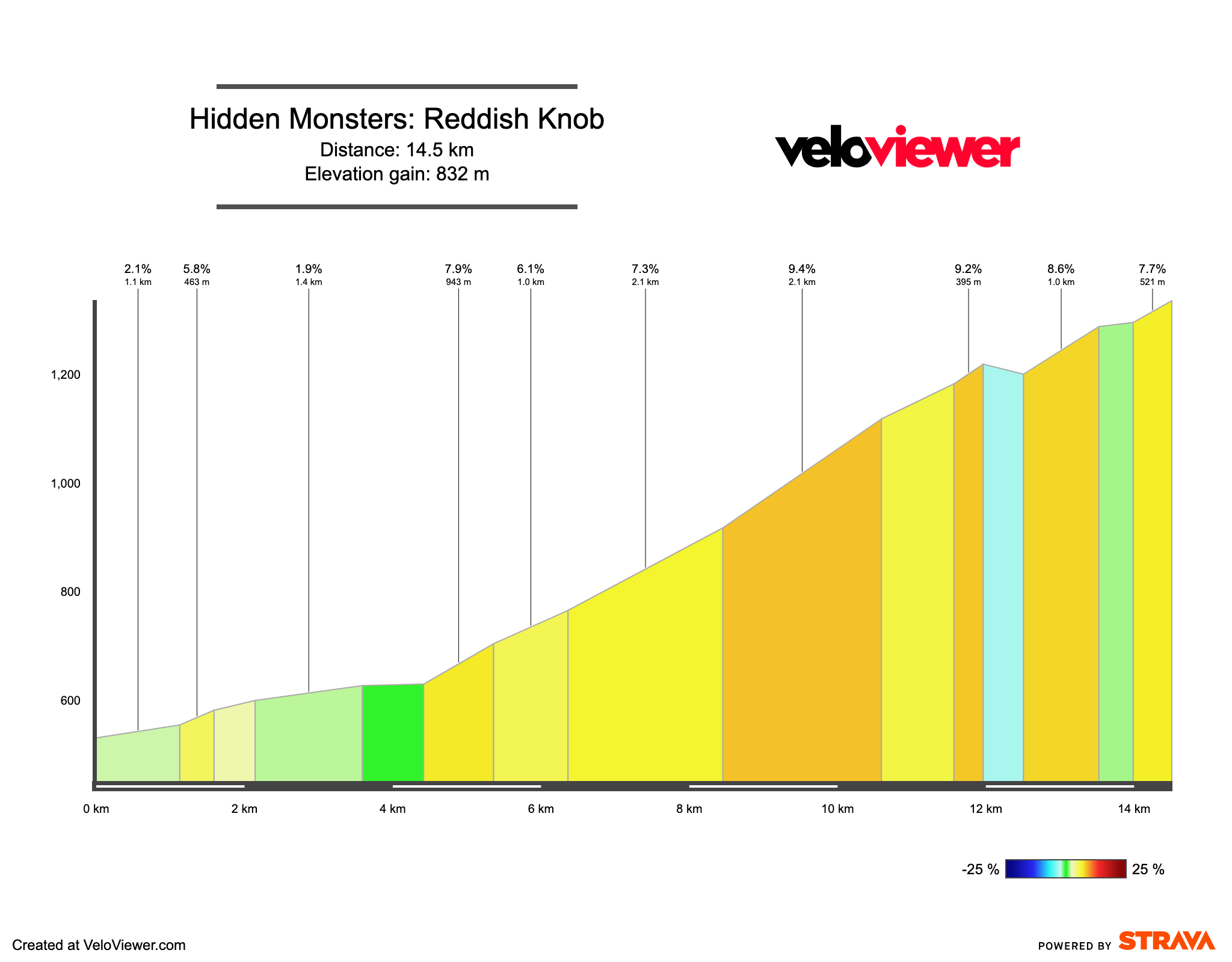

Reddish Knob – George Washington National Forest, Virginia

14.5km (9.0 miles), 5.6% average, 832 metres (2,729 feet)

Strava link

Men’s KOM: Cameron Cogburn – 35:06

Women’s KOM: Jill Patterson – 44:40

If the Rockies are like the Alps, the Appalachian mountains are probably most like the Apennines. What they lack in high-altitude snowcapped peaks, they make up for in rich forest climbs up steep, verdant ridgelines. While most of the climbs along the Appalachian Mountains are short and steep ramps, a few are extended enough to be considered monsters in their own right.

Of those tests is Reddish Knob, which travels up to the West Virginia border from the Virginia cycling city of Harrisonburg. The stats might not be the most impressive, but the climb delivers the goods nonetheless, with a narrow road winding its way up a steep knife-edge of a forested ridge line providing constant views of the nearby mountains and the rich Virginia forests.

While the other climbs on this list use National Park infrastructure to bring roads up to rarified heights simply for the heck of it, Reddish Knob paves a path to the top of the Shenandoah with little rhyme or reason. There is no real infrastructure at the top, no ski resort or telephone equipment that the other big climbs in the area accommodate, yet still the road exists for the pleasure of cycling.

The road's lack of a true reason for existence has meant that it has fallen into a slight state of disrepair, especially after the left turn that extends the climb beyond the saddle that heads down to the hollers of West Virginia. Nevertheless, it is worth dodging around some potholes to wind your way to massive views across both West Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley.

What’s more, once you make it to the top, there is fun for every type of bike available to sample with paved, gravel and singletrack options starting from the top of the knob. For any East Coast cyclists, Reddish Knob is a bucket list climb no matter your area of interest in cycling.