Hershel W “Woody” Williams was a 21-year-old Marine Corps corporal when he watched from the bloodied, ashy beaches of Iwo Jima as the Stars and Stripes rose atop Mount Suribachi on 23 February 1945.

Captured in a Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph, the scene became one of the most indelible images of the Second World War and the inspiration for the Marine Corps War Memorial near Arlington National Cemetery – a moment of American heroism cast in bronze.

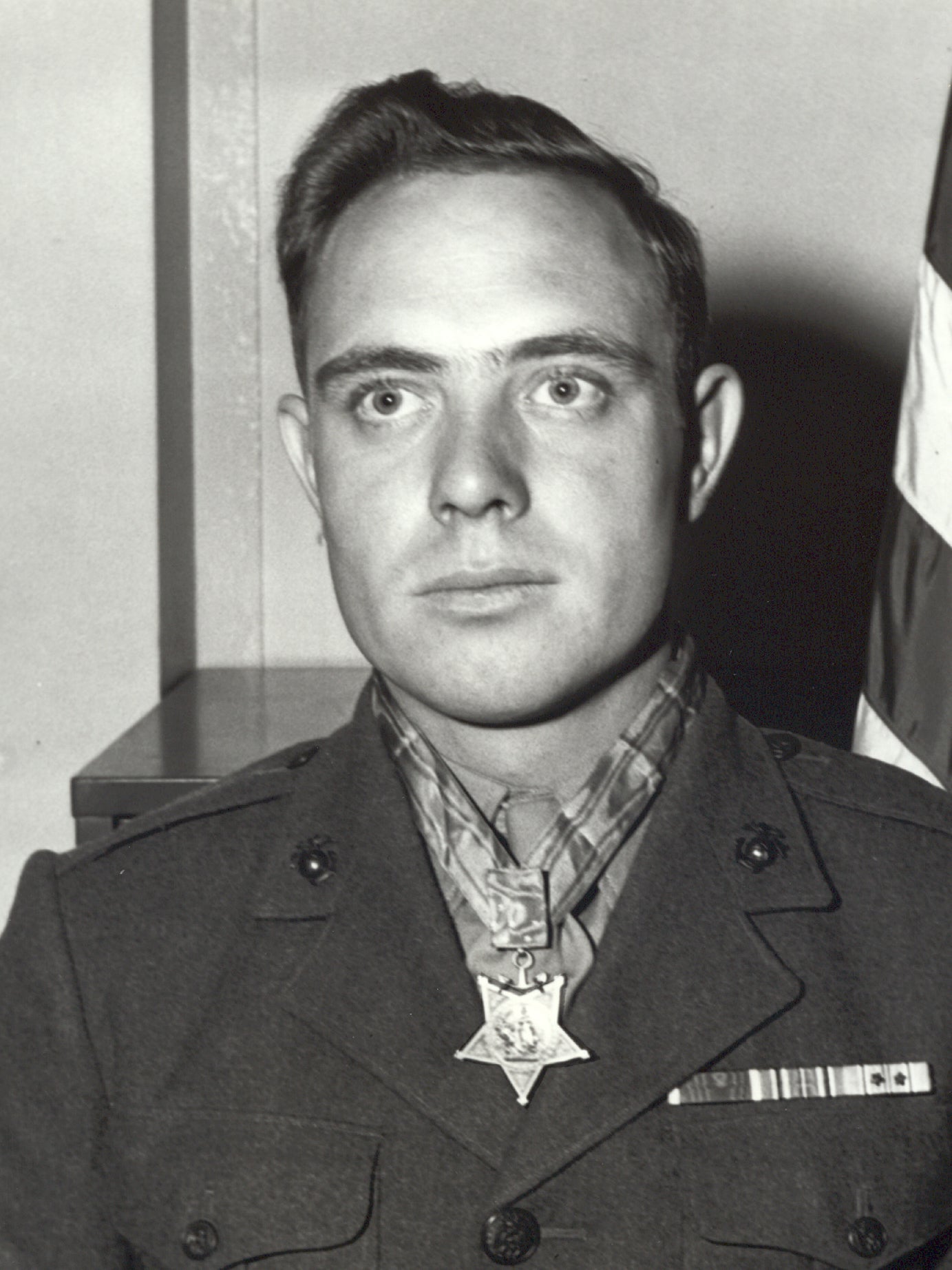

Williams was remembered for another act of heroism that day, one for which he received the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award for valour. Armed with a flamethrower, he braved hours of unremitting enemy fire to take out seven pillboxes where the Japanese had hunkered down to repel the US invasion of the island.

He was one of 27 marines and sailors to receive the Medal of Honour for their actions at Iwo Jima, where 7,000 members of the service died in the bloodiest battle in the history of the Marine Corps. He was one of 472 American service members to receive the medal for their service in the Second World War and was the last of them to survive.

Williams died on 29 June aged 98. His death was announced by the Woody Williams Foundation, a nonprofit organisation that serves Gold Star military families, and by the Congressional Medal of Honour Society.

Williams received the Medal of Honour from President Harry S Truman in October 1945, months after the Japanese surrender marked the end of the war. He regarded himself as only a “caretaker” of the award, which he said belonged more to the marines who did not come home.

Home for Williams was a dairy farm in West Virginia, where he was born Hershel Woodrow Williams in the small community of Quiet Dell on 2 October 1923. He weighed 3½lb at birth. His mother assumed she would lose him, like the several children she had lost in the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Williams was 11 when his father died of a heart attack. To support himself and his family, he joined the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Depression before driving a taxi, the Associated Press reported, at times delivering telegrams to the families of soldiers killed in the early days of US involvement in the Second World War.

Two of his brothers served in the army. Their service was not enough to entice Williams to the branch. He disliked the army’s “old brown wool uniform” – the “ugliest thing in town,” he told The Washington Post decades later – and much preferred a marine’s dress blues.

Williams tried to enlist in the corps after the Japanese invasion of Pearl Harbour in 1941 but was turned away because he did not meet the minimum height requirements (he was 5ft 6in). Months later, the service loosened those requirements and Williams was accepted.

He participated in the invasion of Guam in 1944 before landing the following year at Iwo Jima, where he encountered a scene for which nothing in his previous experience had prepared him. “All the jungle cover had been blown away,” author Peter Collier wrote in the book Medal of Honor: Portraits of Valor Beyond the Call of Duty. “The beach became a slaughterhouse.”

The invasion of Iwo Jima began on 19 February 1945. Williams landed two days later. Two days after that came the flag-raising at Mount Suribachi captured by AP photographer Joe Rosenthal.

“The marines around me started yelling and screaming and firing their weapons in the air and jumping up and down,” Williams recalled to The Virginian-Pilot newspaper in 2011. “I really couldn’t figure out what was going on,” he added, until he looked up to the mountain and “there was Old Glory flying”.

The sight helped push Williams forward into the crucible that he was about to face. He had limited memory of the battle, he said, which took the lives of his best friend and two men sent to cover him. But his medal citation describes a display of courage that was “directly instrumental in neutralising one of the most fanatically defended Japanese strong points encountered by his regiment”.

In one moment, Williams crawled on his stomach to reach the top of a pillbox, stuck a flamethrower nozzle down a vent pipe and squeezed the dual trigger, killing Japanese soldiers firing on his fellow marines. He remembered that perhaps too well, he said in an interview with The Post in 2021.

But when his Medal of Honour citation was read eight months later, as Truman hung the blue ribbon around his neck, Williams said he did not recognise other details in the account of his actions, as if they referred to someone else entirely.

The flamethrower fuel provided only about 72 seconds of trigger time, and Williams returned repeatedly to replenish his weapons as he opened a path for the infantry through Japanese fortifications and mines. He could not remember any of those trips, he said.

“That bothered me all my life,” he told The Post. “If you make up your mind you’re not going to remember something, you won’t remember it. Apparently, I did that.”

He was wounded by shrapnel and received decorations that included, in addition to the Medal of Honour, the Purple Heart. He attained the rank of chief warrant officer four before pursuing a career with what is now the Department of Veterans Affairs, where he spent years as a veterans service representative while also running a horse farm.

Williams’s wife, Ruby Meredith Williams, died in 2007. They had two daughters, Travie Jane and Tracie Jean, and several grandchildren, but a complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

To the end of his life, the last surviving Medal of Honour recipient from the Second World War kept in his kitchen several vials of sand from the beaches of Iwo Jima.

Hershel Williams, former marine, born 2 October 1923, died 29 June 2022

Alex Horton contributed to this report

© The Washington Post