It feels like just yesterday that Gloria Bobertz was on a cross-country trip with her cousin Kristina, the two girls bonding and gossiping late at night about boys and life as only adolescents can do.

“She was just a beautiful soul,” Bobertz tells The Independent, fondly speaking of the cousin just one month older. “That summer I spent with her… I’ll never forget it. She made an impact on my life.”

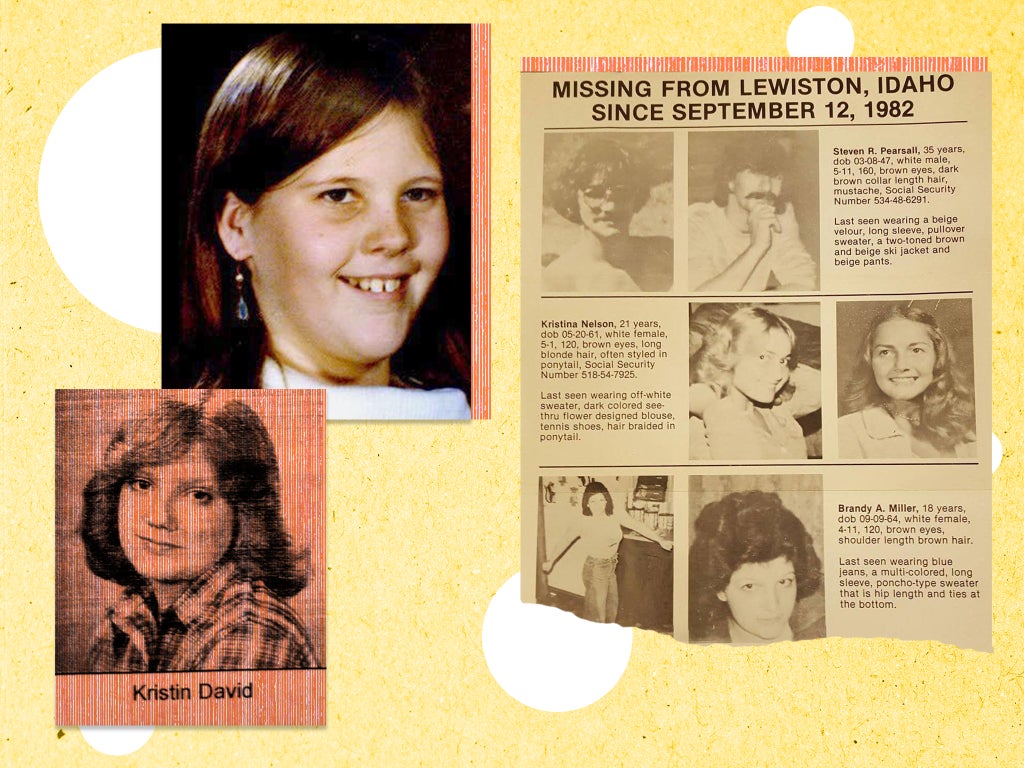

But the treasured memories date back more than four decades, and there’s a bittersweet edge to Bobertz’s voice as she describes them. Because Kristina Nelson would later vanish in Idaho along with her stepsister, Brandy; their bodies would be discovered 18 months after they were reported missing, about 35 miles away. The case has never been solved.

And the mystery of their deaths has only been deepened by questions surrounding other victims from the area who vanished or were killed around the same time. Five people, ranging in age from 12 to 35, varying in both gender and physical description, went missing in the Lewiston-Clarkston – or Lewis Clark – Valley, which borders northern Idaho and southeastern Washington. Lewiston is in Idaho; Clarkston in Washington.

A schoolgirl, Christina White, vanished in 1979 in Asotin, Washington; two years later, the dismembered body of Kristin David was found by a fisherman on the Snake River, which borders the states.

Then came the murders of Nelson, 21, and Miller, 18, who left a note on a September 1982 night saying they planned to do chores but never returned. An acquaintance a generation older, whom they knew from the local theatre and neighbourhood, also vanished that evening. And Steven Pearsall has never been found.

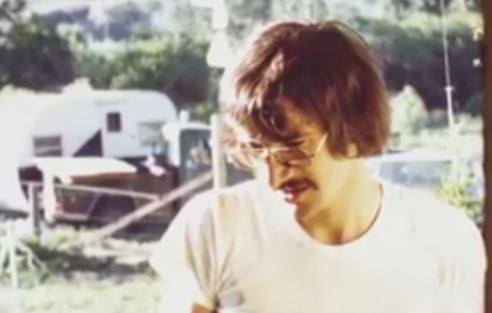

The 35-year-old was a janitor at the Lewiston Civic Theatre, where Nelson also worked and Miller socialised; police attention, understandably, initially focused on Pearsall as a suspect. His girlfriend said they’d been at a party and she dropped him off to do laundry and practise his clarinet on the night in question. Character references, however – and the discovery of his car and uncashed pay cheques in his home – soon diverted suspicion away from the janitor.

“Friends and family said that he would not have left home and left his clarinet behind,” Detective Jackie Nichols of the Asotin County sheriff’s department – who has dedicated herself to these regional cold cases – says in the 2018 Investigation Discovery documentary Cold Valley.

Theories and suspects abound in the minds of investigators, locals and armchair detectives who’ve picked up on unsolved and seemingly connected cases over the past four decades. Many believe the victims fell prey to a single man, one who could have been active before and since the spree in the Lewis Clark Valley.

“I’m sure there are more victims out there,” Bobertz, a mental health specialist from California, tells The Independent.

The first known valley case, which prompted investigators to begin connecting dots, dates back to the 1979 disappearance of Christina White.

The 12-year-old was a playful, normal big sister in quintessential small-town America when she grew up in Asotin, just across the Snake River from Idaho. On 2 April 1979, she’d attended a town parade but felt unwell; the pre-teen was known to suffer from heat stroke symptoms in severe weather. She called her mother, who told her to go home and apply a wet towel to lessen her discomfort.

Neither Christina nor her bike was ever seen again.

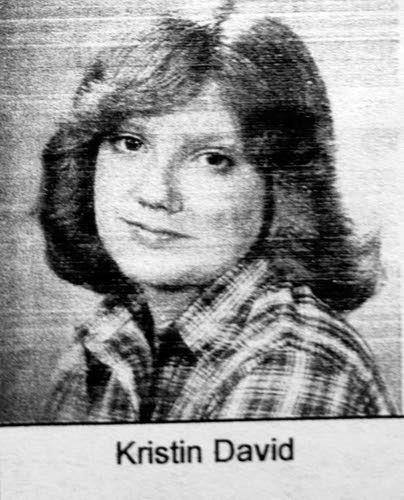

The community searched and was shaken, but fear deepened two years later when a University of Idaho student, Kristin David, also disappeared. Like young Christina White, the 22-year-old had departed on a bike from Moscow, Idaho – about 40 miles north of Asotin – with the intention of driving to Lewiston on 2 June 1981.

Her family knew something was wrong when she fell out of contact and didn’t turn up to work, both developments extremely unusual for the young woman. Her body was found just over a week later by a fisherman, dismembered, tightly wrapped in newspaper and placed in rubbish bags a few miles from the Red Wolf bridge over the Snake River.

Her bicycle, too, remains missing to this day.

“Such a case would be alarming even in a big city, but that was really alarming in a small community like ours,” Detective Nichols says in Cold Valley.

But then things got even weirder – and scarier for valley communities.

On 12 September 1982, Nelson and Miller headed to buy food and do laundry, according to a note they left behind in the former’s Lewiston apartment. They would have passed the Lewiston Civic Theatre on their way; inside, according to his girlfriend, Pearsall was practising his clarinet and also doing laundry on the same night.

The trio knew each other, but none would ever be seen alive again. The female stepsisters were found murdered the following year; Pearsall has never been heard from or found but, according to authorities, is presumed to have fallen victim to the same killer.

“I really, really believe that Steve is deceased, and his body was placed somewhere else away from where the two girls’ bodies were recovered – just to throw us off,” retired detective Don Schoeffler tells Cold Valley.

“It’s the thing that’s going to break this case open… the discovery of Steve Pearsall’s body,” he says. “I think that would do it.”

Bobertz, who repeatedly visits Idaho in her quest to achieve justice for her cousin, has her own theory about the night in question – a theory squarely centred on the same suspect who knew the theatre trio as well as Christina White and whose name she initially heard from the 12-year-old’s mother.

“I think that Brandy went over to Kristina’s house. They decided to go to the store; there was a Safeway down from the theatre,” she tells The Independent. “We have walked … the route they would’ve taken; there was a place called the Red Baron. [The suspect] was down there having a beer.

“I think their paths crossed.”

Her cousin, she says, knew the man from the theatre, as did Pearsall, who’d become a janitor after Nelson gave up the job.

Bobertz believes the suspect, known to all three, convinced the girls to let him give them a lift.

“That’s where I think he got them – in the theatre,” she says. “I think that he probably killed Brandy first to get her out of the way; I think [Kristina] was the main target.

“When that was going on, he didn’t expect Steven Pearsall to come back,” she adds – and when the older janitor showed up, “I think [he] was collateral damage.”

The suspect mentioned by Bobertz – whose name is infamous locally – had lived in Christina White’s neighbourhood, known the Lewiston Civic Theatre victims and possibly had peripheral associations with David. He’d previously been arrested on the west coast, was questioned by police and now lives across the country.

The Independent is withholding his name for legal reasons.

He’s never been the only suspect, however, and investigators have never been entirely sure that all of the victims – particularly David – were killed by the same person or persons.

“This case absolutely fascinates me on a number of levels,” former FBI agent Bradley Garrett tells Cold Valley.

“There is one person that Jackie and other investigators believe are linked at least to four of the cases here, perhaps five – and what I find interesting is that he knew all of them. None of them were strangers,” he says. “Christina White was a child, basically, who was in his house, I’m gonna guess, more than once, just because of proximity.”

Nelson, her stepsister and Pearsall “had sort of worked around him in some form or fashion,” Garrett says, adding that it’s “a little bit unique for serial killers to kill people that they had that sort of relationship with – but clearly not impossible.”

Bobertz, however – along with many people who still live in the Lewis Clark Valley – remains convinced that the deaths and disappearances were the work of one man, an individual still free who they fear killed before and after his time in their corner of the northwest.

“He’s just living his life,” she tells The Independent, adding that she’s not afraid of the man – because, if anything ever happened to her, he’d probably be the first person police would investigate.

She believes he’s responsible for cases as far back and far away as a 1963 murder in Chicago of an eight-year-old girl – and could even be a famous murderer like the as-yet-unmasked Zodiac Killer. Nothing, to Bobertz, is beyond this suspect’s capability.

Former FBI investigator Garrett, however, is not as convinced that one perpetrator has been responsible for all the Lewis Clark Valley victims, and law enforcement has so far shied away from fully linking them – even seeking to distance the David murder from the others.

“So as you look at the cases here in the valley, the one that sort of … [stands] aside from the other ones, in other words doesn’t fit in on the surface, the same MO, is Kristin David,” Garrett says in Cold Valley. “We don’t really know how she died … but the key element in that case is the dismemberment.

“I’ve worked dismembered cases, and the people that are into that is a whole different animal. Think about what you would have to do to dismember a body: you would have to have a location. You’d have to have the time. You have to have the wherewithal. You have to have the equipment. I mean, it really gets gruesome.

“I think it’s realistic that you may, here in the valley, have two killers.”

Regardless of the killer’s identity, however, Bobertz and other advocates are pushing for legislation to broaden authorities’ DNA database.

“So many people think you can plug DNA into CODIS [the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System] and, bada bing, bada boom, you have your suspect and all victims and all that – and that’s not the way it works,” Bobertz tells The Independent, hoping to make DNA records more like those of fingerprints.

She adds: “Any time I get a public platform to push this, I do – and what it would be is, if you are linked to a homicide, if you are a suspect or you’re linked circumstantially to a crime, you get your DNA taken, and it gets put into CODIS – and this would probably solve a lot of cold cases … you’re going to be either guilty or not; [if not,] you move aside.”

Her goal, she says, is to bring solace not only to her own relatives but to others struggling with loss in such uncertain, gruesome circumstances.

“It’s been quite a journey,” she tells The Independent. “When you start this, you realise how many more victims are out there – not just your family members, but others.

“It’s kind of like belonging to a family, but it’s a different kind of family. You’re related by one thing – and that’s death. Murder.”