A growing number of people living in the UK are going abroad to have tattoos, piercings and cosmetic surgeries. Any procedure, no matter where it’s performed, can carry the risk of injury and infection.

But people heading abroad for cosmetic procedures may want to be extra cautious – with recent reports suggesting thousands of UK residents may have unknowingly contracted hepatitis C this way.

Over 170 million people worldwide are estimated to have hepatitis C. There are approximately one million new infections each year. In England, more than 70,000 people had hepatitis C in 2022. But many more could unknowingly be infected, as hepatitis C symptoms can take years to show up.

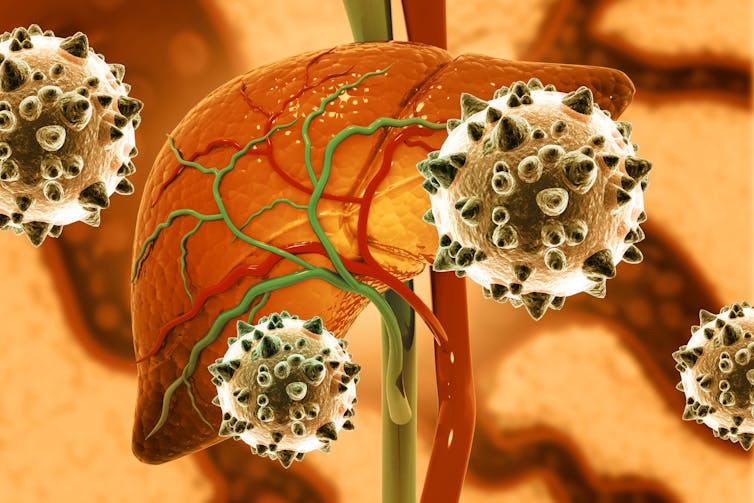

Hepatitis C can develop into severe and fatal liver disease if undiagnosed. But when caught early, treatment is over 95% effective – highlighting just how important timely testing is.

What is hepatitis C?

Hepatitis C is caused by a virus that infects the liver. This virus is spread via contact with infected blood.

Most transmission occurs via contact with contaminated implements, such as needles for recreational drug use. In rare cases, hepatitis C can also be spread through sexual intercourse, or from an infected mother to an infant during childbirth.

Around 80% of people who contract hepatitis C will exhibit no symptoms whatsoever. The 20% that do experience a short, flu-like illness – with varying symptoms that may include fever, headache and muscle aches, fatigue, vomiting, diarrhoea and jaundice.

Symptoms can occur from two to 12 weeks after catching the virus. Those who experience symptoms often don’t realise the severity of their illness.

Some people manage to clear the virus without treatment. But up to 85% of those infected develop chronic hepatitis – where the virus remains in the body.

These people can show no signs of illness for years and are often unaware until more serious damage has occurred – which can take decades. Hepatitis C is still very treatable in chronic form, though treatments have better outcomes the sooner they’re received.

Left untreated for years, chronic hepatitis C causes severe liver disease. This can cause symptoms such as jaundice, swollen abdomen and legs, easily bleeding or bruising, intense itching, loss of appetite and nausea.

Cirrhosis (liver scarring) can also lead to brain and nervous system damage due to the build-up of toxins the liver normally removes. This can cause concentration and memory problems.

An estimated one in five people with chronic hepatitis C develop a severe liver cancer called hepatocellular carcinoma. This is the second most deadly cancer globally, with a five-year survival rate of just 10%-20%.

Age, excessive alcohol consumption, having other infections (such as HIV) and the strain of hepatitis C virus you’re infected with can all increase your risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma.

Risk from medical or cosmetic procedures

If proper sterilisation procedures are in place, your chances of contracting any infection is extremely low. But if surgical implements were used on someone with hepatitis C and not properly sterilised, you will probably catch it. Improper sterilisation also carries risk of other diseases, such as HIV and hepatitis B.

Several studies have reported that tattoos done in non-professional settings, such as those received in prisons, carry an increased risk of contracting hepatitis C due to improper sterilisation. Even tattoos done in professional tattoo parlours may carry an increased risk if reusable needles aren’t adequately sterilised between clients.

For piercings, the data is less clear. Many studies have shown no increased hepatitis C risk from piercings – but these studies did not ask participants whether they’d had their piercing done in a professional parlour or at home. However, cases have been reported of hepatitis C being contracted from a piercing, as well as from swapping body piercing jewellery with an infected person – so it’s important to be careful.

Although data is limited, this risk is probably the same for cosmetic and dental procedures. If proper sterilisation practices are in place and you go to an accredited surgeon or dentist, your risk of contracting hepatitis C is very low.

Certain countries have higher incidences of hepatitis C – such as Egypt, Mali, Malaysia, Italy, Thailand and Mauritius. Certain strains of the hepatitis C virus may also be more prevalent in certain destinations.

For example, the dominant hepatitis C strain in Nigeria has a 94-99% treatment success rate. But in Thailand, the dominant strain is associated with rapid chronic liver disease progression and poorer treatment outcomes. It’s worth being extra vigilant if you plan to have a procedure done when visiting these places.

How can you avoid it?

If you’re having any sort of medical, dental or cosmetic procedure, ask about the decontamination or sterilisation process of the implements.

In the UK, councils require tattoo and piercing parlours to use either single-use needles or have proper sterilisation methods to re-use equipment (most commonly via an autoclave). If in the UK, ask to see the business’s licence to ensure they’re registered with a local council.

Other medical procedures, such as botox or fillers, are less tightly regulated. With any injectable, ideally these should be done by a medical professional – such as a nurse or dentist.

If you’re getting a procedure done and are unsure whether the implements are safe, ask to see it before it’s unpacked. Single use, sterile needles are always sealed in a packet.

Poor hygiene can also spread hepatitis C, so check these are being changed between clients and that good hygiene practice is being done (such as washing of hands and changing gloves between clients). If in doubt, I would suggest not getting the procedure done at all.

If you’ve had a procedure done abroad (or in the UK a long time ago), I would recommend ordering a test kit from the NHS. It’s quick, easy and can be done at home. If it comes back positive, get treated as soon as possible as hepatitis C virus is a highly treatable infection.

Grace C Roberts receives funding from the MRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.