Several themes are explored in the touring exhibition Henry Moore in Miniature, currently on show at the Holburne Museum, Bath, but the standout is the impact of war on Moore’s work.

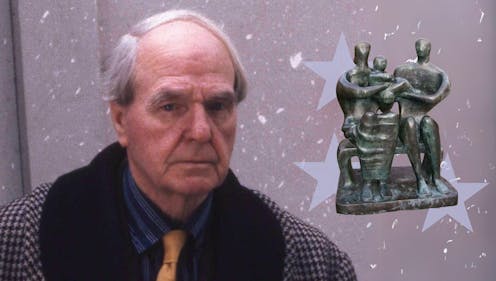

The English sculptor, active from the 1940s to the 1980s, was best known for his monumental bronze sculptures. This exhibition displays more than 60 of Moore’s maquettes – small models created to plan a larger piece of sculpture.

Later in his career, as Europe descended into yet another war, Moore completed Three Points (1939-1940), made from cast iron. The sculpture has surrealist characteristics and although Moore never saw himself as part of the surrealist movement, he was excited by its impact on contemporary art.

Moore said of this sculpture: “This pointing has an emotional or physical action in it where things are just about to touch but don’t … like the points in the sparking plug of a car … the spark has to jump across the gap.” However, for me, this sculpture has distinctly threatening connotations, emblematic of a time of high anxiety throughout Europe.

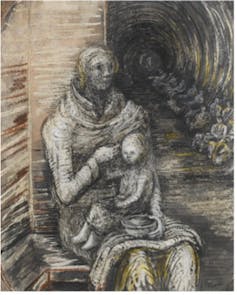

The start of the second world war left Moore questioning his role in the impending conflict. Sir Kenneth Clarke, then-director of the National Gallery (1934-1945) and a lifelong supporter of Moore, appointed him as a war artist. The sculptor was immediately drawn to the subterranean human landscape he had witnessed on the London Underground, where Londoners sheltered from the Blitz.

Moore made a point of never making direct observational drawings from those sleeping in the underground tunnels – but he did capture their plight in a series of memorable drawings completed when returning to his studio. It’s thought Moore made a series of maquettes as a way of recalling these intimate scenes of survival. His “Sleeping Shelterers” drawings may have been based on these maquettes.

These maquettes stimulated Moore’s Madonna and Child series from 1943, and were created as part of his work on a public sculpture now located outside Northampton Church. But they also have an uncanny resemblance to some of his Sleeping Shelterer drawings.

The Madonna and Child commissioned for Claydon Church in Suffolk commemorated local men killed during the second world war. These sculptures are generally seen as the advent of a new sense of realism in Moore’s work, again prompted by his studies of people sheltering in the London Underground.

In 1944, Moore made another series of terracotta modelled maquettes. This time, a male figure is also part of the family unit. The parent figures in the Family Group (1949) studies of this period are protective of the infant. This possibly alludes to the reunification of families after the war.

The exhibition cites these later works as part of the “values of the newly invigorated Welfare State”. These intimately modelled scenes also illustrate Moore’s fascination with how clothing wraps and protects the human form. His focus on drapery was expanded upon in later sculptures, drawings and tapestries.

Moore’s Helmet Heads series of artworks are represented in the exhibition through three memorable sculptures. Although Moore started the series in 1939, he returned to the theme in the 1950s at a time of global anxiety and the fracturing of global unions that had successfully extinguished Nazi Germany.

Moore became a founder member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament at the same time the US, Soviet Union and UK achieved the destructive power of nuclear weapons. These maquettes are cast in lead, which was used as a protective material against radiation while at the same time being a highly poisonous substance. In the Helmet Head sculptures, instead of the protective arms of Madonna and Child 1943 which were cast in bronze, lead is used as a dual metaphor for protection and death.

The post war maquettes of 1950-52 shown in this exhibition suggest a pessimistic view of the state of humanity. These artworks are sinewy, emaciated and dystopian embers of what has been leftover from the destructive powers of war – and potential nuclear technology of the future.

They also demonstrate the lasting impact of surrealism on Moore’s work. Left as brutally unfinished bronzes with jagged edges and exposed seams from the bronze casting process, they suggest disunity, or a fracturing of the human condition.

Moving through the exhibition, Moore’s appreciation of Mycenaean art asserts itself in the series of maquettes called Reclining Warrior (1953) and Maquette for Fallen Warrior (1956), both cast in bronze. Although Moore had long been influenced by Greek sculpture, it wasn’t until his exhibition in Athens in 1951 that he fully appreciated its impact on his work.

In Maquette for Fallen Warrior, we witness the agonising contortions of death as a soldier takes their last breath. It’s a brutal testimony to the human cost of war.

John Atkin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.