The shipping container markets were developed in 1956 by American entrepreneur Malcolm McLean. Since then, the journey has revolutionized global trade.

According to an analysis by The Economist, the shipping container market has been more of a driver of globalization than all the trade agreements in the past 50 years combined. An estimated 90% of the world’s goods are transported by sea with around 60% of this volume shipped in steel containers. Prior to December 2021, liners, freight forwarders, cargo owners, and leading financial institutions lacked tools to efficiently manage their price risk. The launch of the CME Group futures contracts based on index prices from FBX and administered by the Baltic Exchange helps solve that.

Hedging the Cost of Containers

Shipping companies have historically traded container freight using long-term fixed-price agreements. Rates are offered by the shipping liners to the freight forwarders, or in some cases directly to the larger cargo owners. Prices are based on the volume traded. The cost of freight can account for up to 20% of cargo value. Given the volatility in all the major trade lanes, managing the price risk in container freight has become paramount.

Demand Rebound Tests Supply Chains

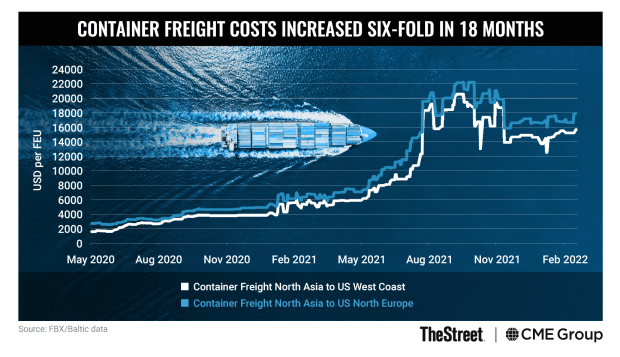

Freight rates have been on a consistent path upwards since May 2020. The lockdowns caused significant disruption to global supply chains with many of the containers ending up in the wrong locations. Subsequent strong demand for goods left many companies facing the prospect of much higher freight costs. Brexit-related stockpiling in the run-up to the January 2021 formal exit of the United Kingdom from the European Union also provided an upwards boost to freight prices on the key European trade lane from North Asia into Northern Europe.

Read more about freight futures and options

Export markets from the U.S. and Europe have faced similar price increases, which also reflects the global displacement of containers. These constraints have put many companies under significant cost pressures with some needing to pass on rising freight prices to their end customers. The situation has left many companies with a need to place a limit on soaring freight container costs. That’s where risk mitigation tools like futures come in. Let’s look at an example of a hypothetical freight owner.

Freight Hedge Scenario for a Cargo Owner

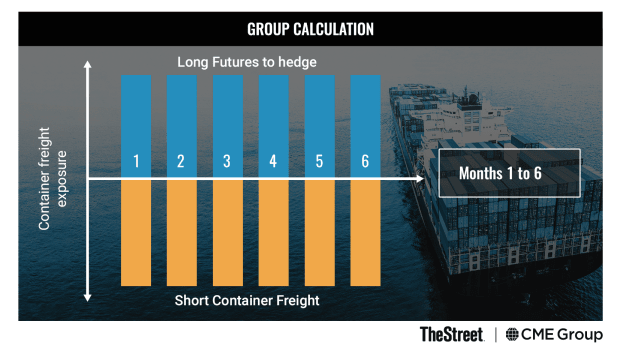

A cargo owner needs to buy 500 forty-foot equivalent unit (FEU) containers per month over the next six months. This is the equivalent of 500 lots of futures with one lot = one FEU. The target price they would like to reach is a maximum of $12,000 per FEU to keep their supply chains intact and ensure that the flow of goods remains unaffected. The cargo owner has a short position in the physical market and therefore to be fully hedged would purchase 500 lots and assume a long position in the futures to align a matched hedge to its physical position. They would be buying either 500 lots per month or may instruct a broker to buy a strip of six months of futures which would equate to a total of 3,000 lots.

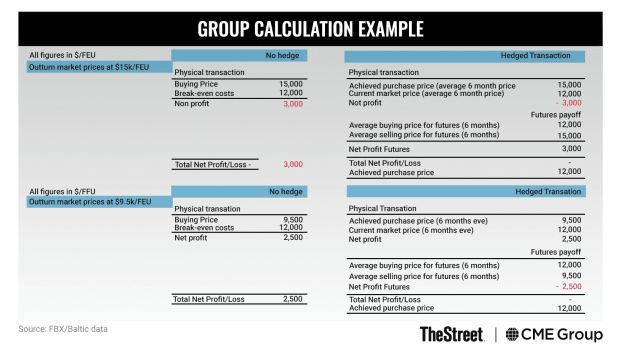

The price for the next six months is $12,000 per FEU as determined by activity in the futures market. Should prices rise significantly above the $12,000 per FEU level there is likely to be additional costs applied down the supply chain. By achieving an assumed average hedged price of $12,000 per FEU for the six-month strip of futures, the cargo owner can deliver all its goods to their end buyers knowing that they do not have to increase their prices significantly. This allows them to maintain their supply price and volume commitments. The table below shows two possible hedging scenarios for the cargo owner.

- The container freight price increases from $12,000 to $15,000 per FEU across the six months.

- Container freight prices fall to $9,500 per FEU across the six months.

In both cases, the cargo owner can achieve a “net purchase price” of $12,000 per FEU by hedging. In the unhedged example where the price rises to $15,000 per FEU, the cargo owner would pay a much higher price for the freight. However, should the price fall to $9,500 per FEU, a lower price could be achieved. By hedging, they can remove the uncertainty about where the price will be in the future.

Trading futures via an exchange requires a company to deposit futures margin, referred to as the initial margin, with a futures broker. Importantly this is not a down payment, and the market participant does not own the underlying commodity. The futures margin generally represents a percentage of the notional value of a container freight contract. The variation margin is the payment made on a daily or intraday basis by a clearing member based on price movement in positions carried by the customer. In January 2022, the cost of a container to ship from North Asia to the U.S. West Coast was $15,000 per FEU. Therefore, the notional value for one contract is $15,000. Any change to the value of the container price will be reflected in the notional value of the contract.

The Risks Ahead for Freight

Despite the supply chain issues of the last year, shipping container usage is only expected to grow. Estimates suggest it could be a $12 billion industry by 2027. Global uncertainty and sudden surges in demand have highlighted the need for managing container price risk. Hedging locks in a future purchase price, which helps liners, cargo owners and other participants meet their target price, regardless of the direction of spot market prices. The hedge transaction is achieved with cash-settled container freight futures based on one of six FBX container indices. By using cash-settled instruments, the participants avoid taking any delivery risk in their hedging activities. That can be a critical tool in managing container risk and could mean passing fewer costs down the supply chain.