Sitting on the street outside her house in Tame, a small town in Colombia near the Venezuelan border, Karen Gomez Romero smiles indulgently at her son Carlos as he careens up and down the pavement, chattering to neighbours and offering his toy truck to passers-by.

The 19-year-old single mother is happy, she says, to see her son playing again. “He used to be lying on the bed, sad and with no energy,” she says.

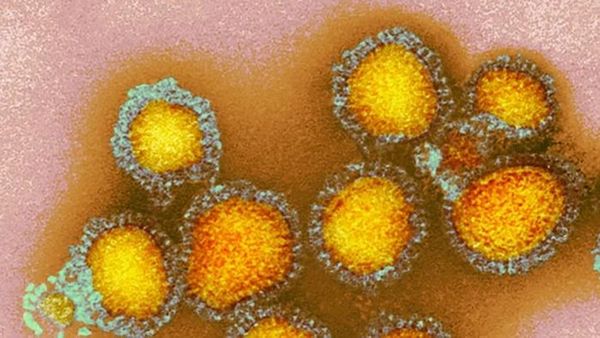

Eight months ago, she had rushed the three-year-old to the nearest hospital, listless and with a high fever. Doctors there had diagnosed Carlos with Chagas disease, a potentially life-threatening and neglected tropical illness caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi.

Endemic in 21 countries in Latin America, Chagas is transmitted by the triatomine insect or “kissing bug”, a small winged insect which feeds on people’s blood while they’re sleeping, and mostly affects rural communities living in substandard housing.

When asked whether, after a gruelling two-month-long treatment regimen, Carlos has recovered his energy, Gomez Romero laughs. “Maybe too much!” she says, grabbing the boy as he shoots past and scooping him up into her lap.

Doctors were able to identify Carlos’ infection at an early stage and offer the treatment he needed. But the toddler is one of the lucky ones. Chagas disease affects up to 7 million people worldwide, yet only 1 in 10 are diagnosed.

In most instances, those infected won’t even know they’ve caught Chagas disease due to an absence of symptoms. However, in up to 30 per cent of cases, the disease can progress over the course of 10 to 20 years, culminating in serious heart complications that trigger sudden cardiac arrest and death.

The effects and burden of the disease are particularly acute in Latin America, where more people die from Chagas than malaria (an estimated 12,000 every year).

In Colombia, it’s estimated that 438,000 people are affected by Chagas, with more than 130,000 people presenting clinical complications. In Argentina, between 350,000 and 500,000 have already developed heart disease linked to the progression of the disease.

But despite the challenges posed by Chagas, there is little public awareness or funding available for research across South America.

This neglect has been particularly stark in Colombia’s conflict-afflicted regions such as Arauca, in the country’s northeast, where for decades the presence of armed rebel groups made it impossible for the state to provide even basic healthcare services.

‘That’s the bug that bit my son!’

Whilst relief was initially promised by a 2016 peace agreement, signed between the Colombian government and rebel groups in an attempt to resolve the country’s five-decade-long civil conflict, factions who were opposed to the agreement soon began to fight amongst themselves.

The ensuing violence means that travel in the state continues to be fraught with danger, leaving many communities isolated.

“It is difficult for the community to go to the health services, and also for the staff to go to the community,” explains Andrés Cuervo, head of the vector-borne diseases programme in Arauca’s health department.

He estimates that around 20 times per year, violence flares up to such an extent that movement is impossible, creating “a chasm between the community and the healthcare workers.”

Now, however, a combined effort from the state health department and international organisations such as Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) has helped develop a unique approach to delivering diagnosis and treatment across the region.

Trained local healthcare workers are at the centre of the new model. When Carlos was rushed to the hospital, doctors trained to recognise the symptoms of Chagas disease immediately spotted what looked like a bite mark on his face.

Suspecting Chagas, they showed Gomez Romero images of the triatomine insect which spreads the parasite. “They showed me photos, and I said yes! That’s the bug that bit my son!” she recalls.

Detecting Chagas in the acute phase, just after infection, is the key to fighting the disease, says Cuervo. Chagas is known as a “silent disease” because, after the acute phase when patients can present with a high fever, symptoms usually abate.

If doctors fail to diagnose and treat the disease during this initial period, it often goes undetected for decades, silently causing irreparable damage to the heart and other vital organs. By the time the patient notices this damage, it is too late; most Chagas-related deaths are caused by organ failure.

By training local healthcare workers to recognise Chagas symptoms and risk factors however, the number of cases diagnosed annually in Tame, in northeast Colombia, has increased from just 22 in 2007 to around 800 last year.

“That’s something to boast about,” says Cuervo. “Before in this department it was impossible to detect an acute case of Chagas.”

‘We started talking and realised that everyone had Chagas’

Having technology available locally can also help these healthcare workers to detect both acute and chronic cases of Chagas.

An electronic reader which detects the presence of antibodies in blood samples was donated to the local hospital in Tame in 2018. Whereas confirmation of a positive Chagas case would previously take 4 to 5 months, the new technology means that laboratory technicians can now get results back to patients within around 8 days.

This has allowed staff to drastically increase the number of patients they can test and run regular screening programmes.

Patricia Alvarez Figueroa was diagnosed thanks to one such programme, which advertised for volunteers in Tame to come to the hospital to get a blood test. When her test result came back positive, she was shocked, she says. She had only taken the test because she was accompanying her sister to the hospital, and hadn’t previously suspected she had the disease.

Spotting many of her friends and neighbours during regular check-ups at the hospital, the 53-year-old soon realised that many others were in the same boat, however. “We started talking and realised that everyone had Chagas,” she says.

At first she was reluctant to take treatment, worried about side effects. But, she says “the hospital called me all the time, to try to convince me.”

Local staff are important for gaining trust and following up on hesitant patients like Alvarez Figueroa, explains Phanor Parada Solano, technical lead of the vector-borne diseases programme in Tame.

“They will be able to follow the patient and everything the patient needs, to be part of the process of the treatment,” he says.

But, says Cuervo, “our job is not just to get a diagnosis and treatment. It is also to guarantee that patients don’t get reinfected.” To do this, community-led disease surveillance is essential in order to monitor the disease, even when the health department team is unable to travel.

Training sessions conducted in small communities teach residents how to identify and safely collect insects that they find around the home, and then leave them at a designated collection point in their village, to be picked up by health department workers at a later date and transported to an entomology laboratory in the department’s capital.

“They explained what to do if we found them, and showed us photos,” says Ciro Lopez Lozada, who also lives in Tame and is currently undergoing Chagas treatment. The 59-year-old suspects he contracted the disease after being bitten by a triatomine insect, which he often finds around his home.

“The community helps the health system to recognise the vector and where they found it, because we can’t go all the time to the community,” explains Cuervo.

The information collected by the community, along with details on what their houses are made of, how long it takes them to reach the nearest healthcare centre, and other risk factors such as whether they keep animals inside the house, has helped Cuervo and his team to create a comprehensive epidemiological risk map.

This not only provides them with knowledge on where to focus efforts for health promotion and prevention strategies, but also acts as a reference point for the whole continent, says Cuervo.

Whilst the programme has so far achieved some level of success – around 50 percent of Arauca has been certified Chagas-free – it is proving more difficult to bring about change in certain areas, especially those close to the mountains.

“It’s a problematic zone,” says Cuervo. “Because of the weather, because of the conflict, and also because of the geography, it’s really difficult for the doctors to get access.”

An ongoing study, carried out between DNDi and Colombia’s national health institute, hopes to provide one solution. If successful, it will prove the efficacy of rapid diagnostic tests, which could be operated by local volunteers with minimal training, says Cuervo, providing an instant diagnosis to people living in even the most inaccessible areas.

“The rapid tests would change the whole game,” he says.

In the meantime, however, says Cuervo, the team will continue to travel to hard-to-reach communities, occasionally by boat or even horse – and often at great personal risk.

Last year, the central government instructed the health department in Arauca to stop supplying the drugs used to treat Chagas disease to the armed rebel groups. The move was deeply controversial, as many of the members have Chagas disease themselves.

“Most of the armed forces live in the forest, high in the mountains,” explains Cuervo. “So it’s really easy for them to get Chagas.”

Previously supportive of the health department’s work to combat the disease, one illegal group decided to retaliate, attempting to kidnap Cuervo at gunpoint. Fortunately, he managed to escape unharmed, although he was forced to leave the department for four months due to ongoing safety concerns.

Despite his ordeal, Cuervo is now back in Arauca – and he is more determined than ever not to stop until the job is done. “I have a vision that one day, we will be free of Chagas,” he says.

Reporting for this article was funded by the European Journalism Centre, through the Global Health Security Call, a programme supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.