British student Matthew Hedges was about to board a plane back to the UK from Dubai airport when Emirati authorities suddenly arrested him, accusing him of being a spy.

It was 5 May, 2018, and the PhD student had just finished a research trip for his doctorate into aspects of the United Arab Emirate’s foreign and domestic security strategy.

While he was there, an Emirati man apparently reported him to the authorities for “asking sensitive questions about some sensitive departments” and “seeking to gather classified information on the UAE”.

Mr Hedges was then accused of working for MI6 and "spying for or on behalf of" the UK government, a charge then head of the secret service Sir Alex Younger personally denied.

For nearly eight months after, the academic says he was interrogated for up to 15 hours a day, force fed a cocktail of medication, kept in a windowless room without a bed and denied regular access to the British embassy and his lawyers. He suffered panic attacks and was placed under intense psychological pressure, before being sentenced to life imprisonment.

It was only after intense, although belated lobbying from the UK government, international outcry and a forced confession that Mr Hedges was pardoned and released on 26 November 2018, the country’s National Day. The UAE called it “gracious clemency”.

Mr Hedges said his ordeal left him with post traumatic stress disorder and insomnia. He still has to take drugs seven years later as a result of being force fed medication.

Two months after Mr Hedges was pardoned, UAE authorities detained another Briton, Ali Issa Ahmad, then 26. The Sudanese-born football fan was arrested in January 2019 after being accosted by security officials for wearing a Qatar football shirt, not knowing that doing so is an offence in the UAE punishable with a large fine and an extended jail sentence.

For around three weeks, he says he was beaten, cut and burnt by police officers, and detained in a security facility. While in detention, he was electrocuted, beaten, and repeatedly deprived of food, water, and sleep. An attempt was made to kill him by stabbing.

“I thought that was going to be my last moments,” he says.

UAE officials claimed Mr Ahmad had harmed himself and charged him with making false statements, and wasting police time. He was convicted without any fair trial, then released on 12 February.

Their cases are just two of “numerous” allegations against the UAE state security system of abuse and torture of prisoners, irrespective of their innocence.

Joey Shea, a researcher for Human Rights Watch who focuses on the UAE and Saudi Arabia, says the allegations they have documented include forced disappearance, prolonged solitary confinement, torture, physical assault, abuse and the use of extremely loud music to stop prisoners from falling asleep.

On Monday, the man responsible for the state security services and police forces that reportedly carried out this torture, and has since allegedly failed to investigate the two cases, will arrive in the UK.

Mr Hedges and Mr Ahmad are demanding that he is arrested.

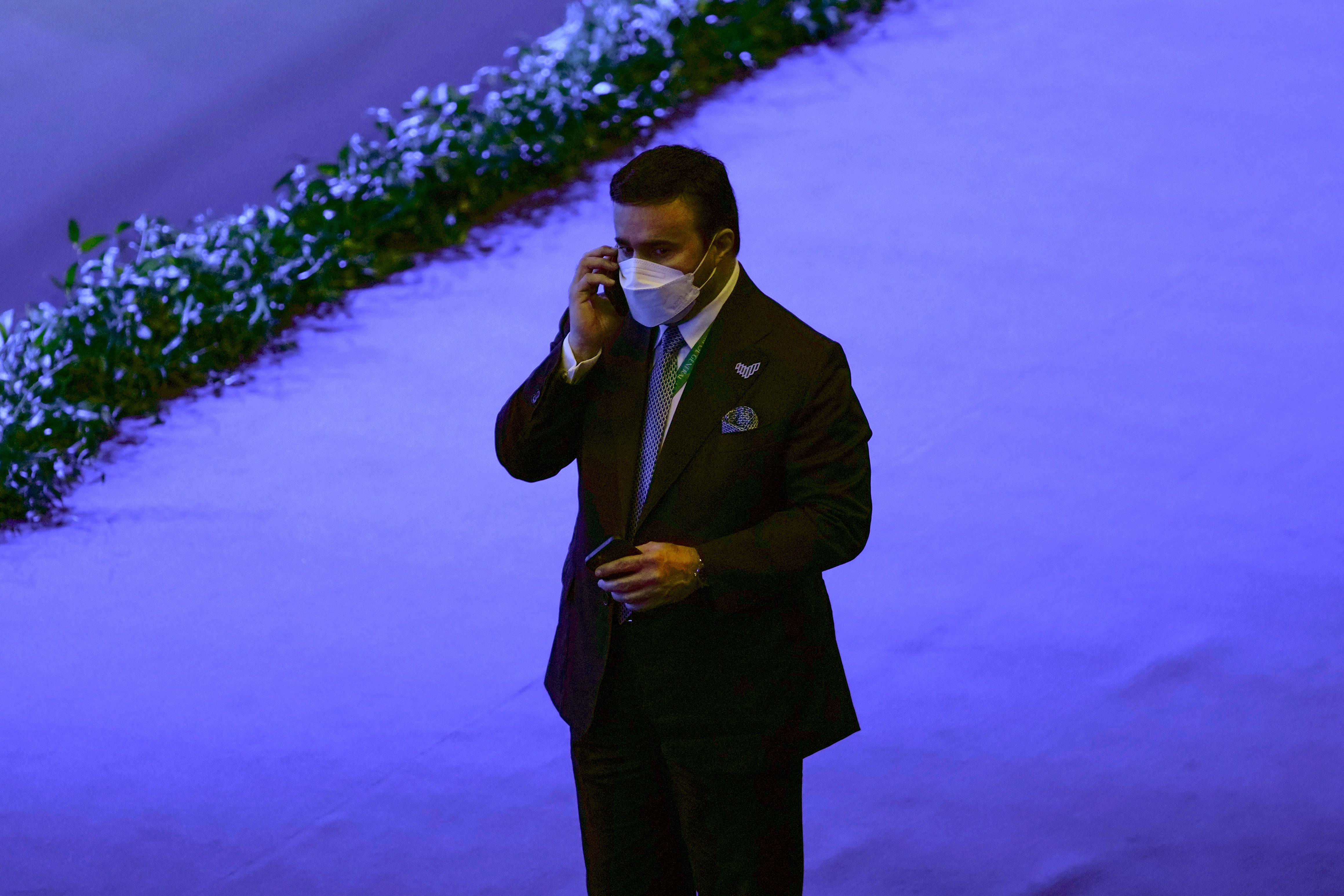

Major General Ahmed Naser Al Raisi, who was educated at the University of Cambridge and received a doctorate from London Metropolitan University, will touch down in Glasgow on Monday for the annual general assembly of the International Criminal Police Organisation (Interpol).

He is the organisation’s director, having been elected in November 2021 despite significant protest. Four years previously, the UAE donated $54 million (£42m) to Interpol, almost equivalent to the required contributions of all the organisation’s 195 member countries in 2020, which amounted to $68m.

Ms Shea says the appointment was a blatant “part of the UAE’s broader strategy to whitewash its reputation and human rights record”.

“His position in that role says a lot about how much Interpol is concerned with human rights,” she adds.

When approached by The Independent about the appointment of Mr Raisi in relation to the allegations against him, an Interpol spokesperson described the matters as “an issue between the parties involved”.

Three months after the appointment, French prosecutors opened a preliminary inquiry into torture and acts of barbarism allegedly committed by Mr Raisi in relation to the cases of Mr Hedges and Mr Ahmad. The UAE has previously denied the allegations.

After Mr Raisi appeared in Lyon, where Interpol is headquartered, the major general was summoned to appear before a French judge to be questioned in June 2023.

He failed to show up for that date. A day later, the judge resumed interviews with the two Britons, and further evidence was provided to help prosecute the Interpol director.

If he visits France again, the judge may request to compel him to give his testimony. Beyond that, they could seek an international arrest warrant.

But ahead of Mr Raisi’s arrival in Glasgow, Mr Hedges and Mr Ahmad are demanding that the Scottish police follow suit and open their own investigation.

“The torture I suffered, the sets of abuses that others have gone through in the UAE, is ultimately under Mr Raisi’s guide,” says Mr Hedges. “Any failings that occur, he is the person that oversees that.”

The pair have submitted a criminal complaint with supporting evidence to the Scottish police against Mr Raisi. It has been filed under the principle of universal jurisdiction, which enables states to arrest and prosecute those involved in torture who are on their territory, regardless of where the crimes are committed.

Rodney Dixon KC, Temple Garden Chambers, London and The Hague, who acts for Mr Hedges and Mr Ahmad, says they believe the evidence submitted “shows [Mr Raisi’s] responsibility for both cases” given his role as inspector general of the interior ministry since 2015.

It includes medical evidence of what happened to both men and issues they are still grappling with.

The purpose of the complaint is two-fold, says Mr Dixon. It aims to show Mr Raisi’s “complicity” in the initial acts of torture and his subsequent “command responsibility” for failing to investigate those acts when the UK Foreign Office issued a formal complaint to the UAE about the two men’s cases.

Ms Shea says beyond the two British cases, she has “received no indication that any allegations have been investigated” by Mr Raisi’s office.

For Mr Hedges, though, the pain of his treatment has for years been worsened by the inaction of the UK government. The Foreign Office may have filed a complaint, but they were forced to apologise to Mr Hedges after a lengthy review for the way they handled his case.

Despite that, the British police have declined to investigate Mr Raisi, which is why, according to Mr Dixon, they are now issuing a complaint to the Scottish police.

“The UK government knows what happened to me,” says Mr Hedges. “How could they know what’s happened and yet still simply let this legal process go by them? Inaction is not an option.”