There is something intrinsically tribal about certain styles of music, particularly within the genres of dance, house or EDM. But, have you ever wondered why we find ourselves counting to 4, before we then go back to 1, and start all over again?

There must be a reason why we don’t keeping counting into the thousands, and the answer lies with the theoretical side of music, and the use of something known as a 'time signature'.

The whole purpose of a time signature is to indicate how many beats there might be to a musical unit known as a 'bar'. (Before you ask, no, it's not that sort of bar!) It's a unit that we use in music to dice up the beats into a manageable chunk.

Hence in the case of most commercial tracks, each bar may contain 4 beats. That’s why we count to 1,2,3,4, and then start again in a numerical loop!

In America, bars are often referred to as measures. (No, it’s not that sort of measure, either!)

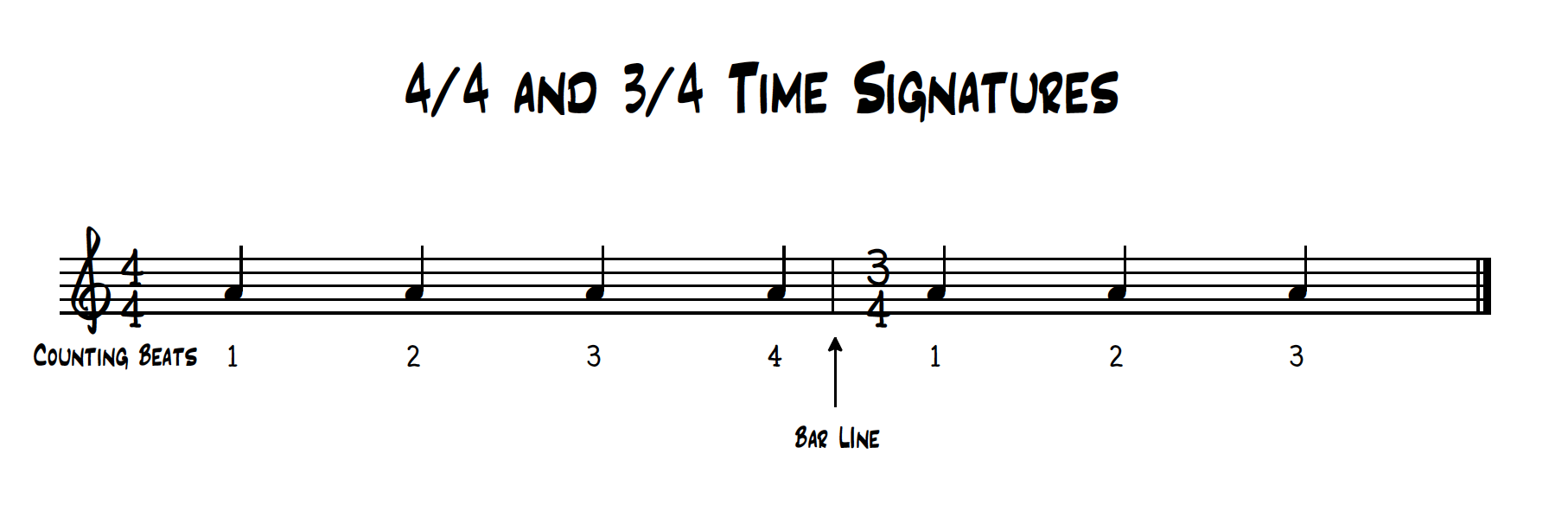

It's very easy to spot where a bar begins and ends in written music, because it is indicated by the usage of a bar line, which goes vertically from top to bottom, across a musical stave. If you have experience with drum machines, you may also notice that they often have 16 steps, usually organised into groups of 4, to align perfectly with 4 beats to a bar.

When reading or writing music, you need to know how to understand time signatures. These are indicated by two numbers, one above the other, a little bit like a fraction. The top number is an indication of how many beats there are to a bar. If it's a four on top, there are four beats to a bar. If it's a three on top… you've guessed it!

The bottom number indicates the type of beat that you are counting. This is best described by having an association with the American system of note values (see our previous article about reading rhythms).

If the bottom note is a 4, this indicates a quarter note or crotchet. Connect this with the 4 which is above, and it means you have 4 crotchet or 1/4-note beats to a bar.

Time for a waltz

You could be forgiven for thinking that all commercial music works to a 4/4 construct, but there are examples that don’t.

Take the time signature 3/4, which is sometimes described as waltz time; if we follow our previous analysis, this means that there are 3 crotchet/1/4-note beats to a bar.

There have been several ballads over the years that adopt a 3/4 time signature, such as the Commodores, Three Times a Lady’, or OMDs, Maid of Orleans.

Sting is also very fond of using time signatures such as 5/4 or 7/4 in some of his songs.

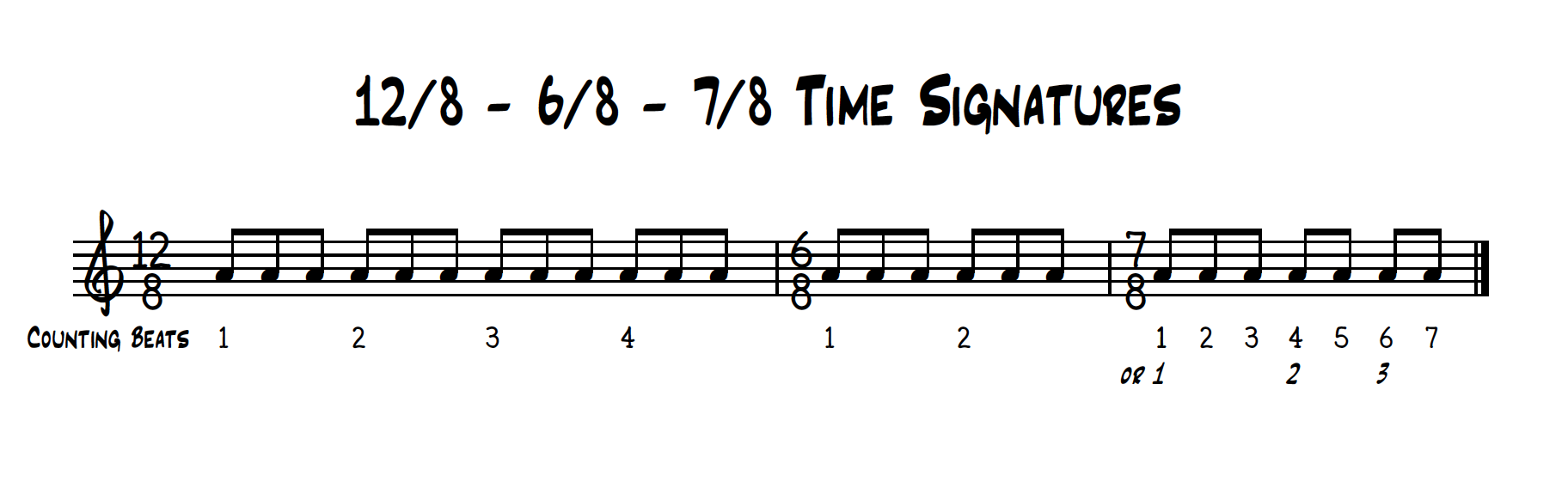

It's also possible to change the bottom number to a different unit; the time signature 12/8 indicates that we have 12 beats to the bar, but what sort of beats?

The 8 signifies a unit of quavers or 1/8th notes, but musical conformity suggests that we tend to count this as 4 to a bar, but with three quavers per beat.

There are quite a few jazz, country and western songs that adopt this time signature, but it's not just the preserve of these styles! Jean-Michel Jarre’s Oxygene (pt.4) is also in 12/8, thanks to the bossanova-style beatbox that he used on the Oxygene album.

Look for the signature

If you are ever unsure of exactly what time signature you are being confronted with, just look at the beginning of the first line of music for the magic numbers. They will guide your way, and dice up your bars accordingly.

And if you've ever wondered what the most bizarre number of beats to a bar sound like, look no further than the classical composer Igor Stravinsky.

His groundbreaking orchestral work The Rite of Spring includes a bar of 11/4! It’s like an avant-garde EDM track, with a limp!