Harry Hyams rose from humble beginnings and went on to change the London skyline for good when he built the 398ft, 35-floor tower, Centre Point, in the heart of the West End. Once described as the “daddy of all developers”, he virtually invented property development as it is known today. Fellow property tycoon Sir Stuart Lipton credited him as “the first man to recognise the importance of skilled planning and development.”

Making his fortune by his early thirties in the post-war years, he set about taking advantage of the opportunities provided by bomb sites in prime locations in the capital. He was particularly shrewd in developing office space during the 1960s and '70s, when rents were rising quickly.

His formula was to keep things simple. He concentrated on central London office space and aimed to attract a single tenant for each building who would take on responsibility for all repairs and insurance. This approach meant that, even at its peak, Hyams was able to manage his entire empire with a staff of six.

Although the construction of Centre Point is now regarded as one of the most important developments in post-war Britain, at the time it sparked much disagreement, particularly the manner in which he gained the land. Designed by George Marsh and Richard Seifert & Partners, it was built between 1963 and 1966 for £5.5m. The tower, Grade II-listed in 1995, was seen as a classic expression of the bright and brash pop architecture of the Sixties, inspired distantly by Le Corbusier and Milan's 32-storey Pirelli tower. The frame of precast concrete sections was claimed as the first in London which eliminated the need for scaffolding.

However, the concrete and glass building attracted huge controversy when it was finished, partly because of its size and style but also because it became a symbol of opportunistic exploitation and a focus for protest against the greed of profit-driven developers during the 1960s office boom. Hyams' single-tenant policy back-fired when a deal for British Steel to take the whole fell through.

Refusing to consider multiple letting, Hyams left the tower unoccupied until 1975 and stood accused of keeping it empty because the growth in its capital value was much higher than the rental loss; its value was estimated at over £22m by 1975. It was condemned in the Commons by Environment Secretary Peter Walker as “an incredible scandal.”

Through his lawyer Lord Goodman, Hyams threatened legal action against anyone suggesting the action was deliberate, and successfully sued the BBC three times. He maintained his innocence until his death.

In 1974, the tower was temporarily occupied by campaigners to draw attention to the plight of London's homeless. Finally, Hyams relented and began to lease the building floor by floor, though it never had full occupancy. From 1980-2014 it was home to the Confederation of British Industry before being converted by its current owners into flats, shops and restaurants.

Born in Hendon, north London in 1928, Harry John Hyams was the son of a bookmaker. Educated at a private school education – where he was friends with the racing driver Graham Hill – at 17 he joined a firm of estate agents before switching to property development.

When he was 31, Hyams and the builder George Wimpey bought Oldham Estates, a Lancashire-based property company, for £50,000, which he uses as a vehicle for a range of ambitious ventures in London. By 1963 the company was worth £23m. Hyams rented in many areas, including the then run-down district of Borough, where he was demanding around 50 per cent more rent than anyone else and although agents could not find tenants, he refused to lower his price. Unilever arrived looking for its Bird's Eye HQ. Company men visited Hyams' building but balked at the rent.

The agent begged Hyams to reconsider. “If they've been around four times, they want it, and they'll pay,” he said. “The extra £5 a foot I'm asking is three salaries at most for Bird's Eye, and they'll be putting 400 people in that building, so what we're seeking is nothing to them. Offer three months' free rent, to show how generous I am, but don't drop the price.” Unilever paid up.

In 1987, Hyams' company was taken over by property giant MEPC who paid £620m, making him £150m; when MEPC was bought in 2000 he pocketed a further £98m.

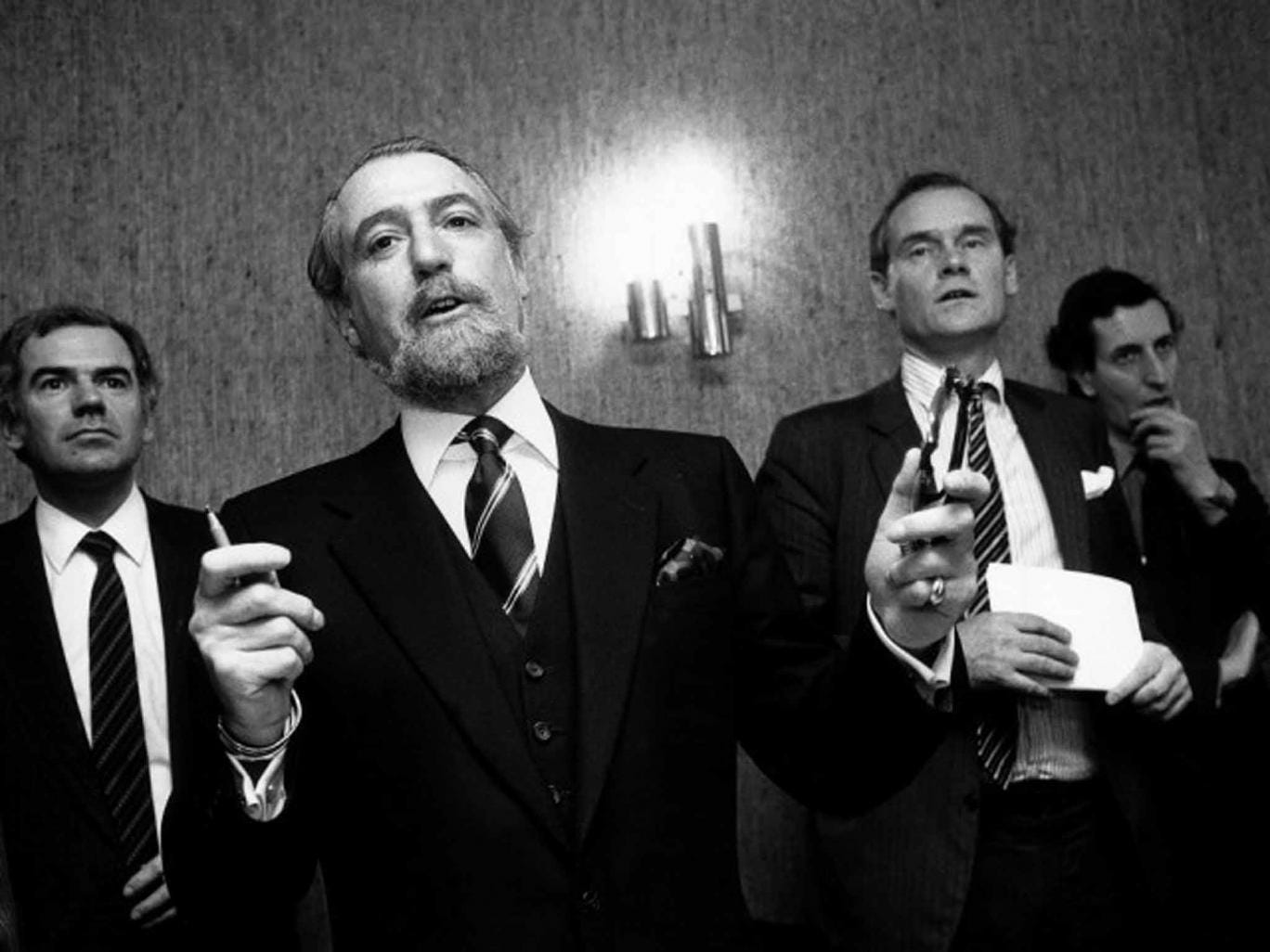

An intensely private man, Hyams' was forced by his unwanted notoriety from the Centre Point storm to find ever more eccentric ways of avoiding the limelight. He held AGMs when he thought attendance might be low, for example, 4.15pm on New Year's Eve. He turned up to one shareholders' meeting in a Mickey Mouse mask to evade photographers outside the Institute of Directors. To this day, few pictures of him have made their way into the public domain because he believed he resembled “a Lebanese street trader”; his voice never made it into the BBC archives as it was never caught on tape.

He retired to Ramsbury Manor in Wiltshire with his wife Kay, whom he had married in 1954. Paying £650,000, he spent millions restoring it. He enjoyed classic cars, powerboat racing and horseracing. He was also prone to impulse buying; he acquired the 212ft Shemara, one of the world's biggest yachts, but did not put her to sea for over three decades; he bought two boxes near the Queen's at Epsom but never used them. He also made anonymous gifts to football clubs and his parish council.

The gentlemanly Hyams was one of Britain's most avid art collectors. He loaned several masterpieces anonymously to art galleries around the country. He reportedly owned Turner's The Bridgewater Sea Piece, one of the artist's finest seascapes, which has been on loan to the National Gallery for almost 30 years.

In 2006, the Hyams were victims of what is thought to be the most valuable domestic burglary in British history, when intruders made off with £80m worth of antiques. They were jailed for a total of 49 years but only half of the stolen goods were recovered. In January 2015, Hyams was still using the law to assert his rights, objecting to plans by Stefan Persson, the owner of H&M, to build a mansion next door to Ramsbury. He argued that this would infringe his game shooting rights. His objection was rejected in the High Court.

Harry Hyams, property developer: born Hendon, London 2 January 1928; married 1954 Kay (died 2011); died 19 December 2015.