When pre-poll voting starts on Monday May 9, it will signal the denouement of one of the least compelling streaming series ever to secure repeat funding: #AusVotes2022.

I guess it helps if your ratings are locked in by law.

As community organisations like the Country Fire Service, Lions Club and Rotary gear up for Australia’s triennial feast of ballot-marking and sausage-eating, it is timely to ask who on each side has risen through the campaign period so far, and who hasn’t. This in turn tells us something about the government we might install.

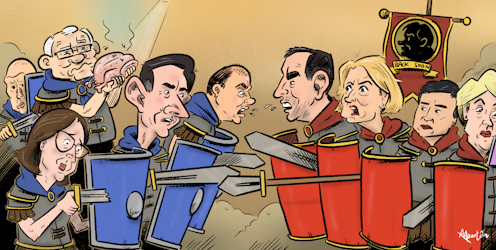

First, let’s consider the Coalition.

Obviously, it is only actual votes that can settle this argument. Or, to put it in political-speak, “there is only one poll that counts”.

That was the standout lesson of the 2019 election. Despite negative reviews of the popularity of the Coalition’s one-man show, Australian audiences actually liked what they heard.

However, in 2022 that one-man approach seems less fit for purpose. Partly this is because the one man is Scott Morrison, who, after boldly explaining he doesn’t hold a hose, may now struggle to hold the house.

It’s also partly because in 2019, Morrison had a persuasive script written for him by his opponents’ plans for tax increases. In 2022, Labor has given him much less to work with, meaning the spotlight has stayed on his own performance.

Complicating things further is that Morrison’s party is trailing in the polls and fighting on three separate fronts: in the regions against Pauline Hanson’s One Nation and Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party; in the middle and outer suburbs against a unified Labor Party; and in its affluent capital city strongholds, against lifelong Liberal voters attracted to centrist independents.

In only one of these distinct battlegrounds, the outer suburbs, is the Prime Minister considered the clear asset he was in 2019. Indeed, in some Liberal heartland electorates, sitting moderate MPs have quietly asked that he stay away.

These differential demands have forced the Liberals to tailor their messaging, and diversify their messengers too.

Tellingly, Morrison has so far not accepted multiple interview requests to appear on the ABC’s flagship political and current affairs programs, including 7.30, Insiders and Radio National Breakfast. He has done just one interview on AM, and that was on the very first day of the campaign when almost all the main broadcasters got an interview.

Much of the burden for these and other interviews has fallen to deputy Liberal leader Josh Frydenberg. Affable, media-savvy and relentless, Frydenberg is probably the most popular politician on the conservative side, and with the economy central to the government’s re-election pitch, has rightly done his share of the heavy lifting.

But he has been distracted back at base by the existential threat he faces in his Melbourne seat of Kooyong. Defending a margin of just 6.4%, Frydenberg is locked in a ferocious local battle to hold off a highly credentialed “teal” independent, Monique Ryan.

It is a real dilemma. Frydenberg might be his party’s friendly face and leadership future, but he needs to stay in parliament for that to mean anything. At times, the stress has shown.

This has placed an even bigger burden on Senator Simon Birmingham. The doughty finance minister is the safest pair of hands on the government side, able to deliver a message, handle tricky interviews, and do it all with an even temper. It helps also that as an upper house member, he is not fighting for his career.

However, after Birmingham, the Coalition’s communications talent becomes noticeably less reliable. The Liberals’ official campaign spokesperson and incoming health minister (if the Coalition survives) is another South Australian senator, Anne Ruston.

She has struggled to cut through with the same command as Birmingham – a situation not helped by Labor’s suggestion she presents a risk to Medicare.

Among the other frontbench voices asked to step forward is Victorian-based Minister for Superannuation and Women’s Economic Security Jane Hume. Again, she has not made a lasting impression.

Others, such as the usually effective communicator Peter Dutton, are problematic. Dutton has probably done more harm than good outside his home state of Queensland – particularly in the seats under threat from climate-conscious “teal” independents.

Ditto outspoken Nationals Barnaby Joyce and Matt Canavan. Even Foreign Minister Marise Payne has not lifted the team after coming across as supine early in the campaign, when Beijing signed a security agreement with Australia’s close Pacific neighbour, the Solomon Islands.

The secretive Sino-Solomons pact was a body blow to the Coalition’s claimed vigilance against a strategically expansive China and against national security threats generally.

So what about Labor?

It sounded trite at the time, but when news broke of Anthony Albanese’s forced COVID isolation for week three of the campaign, Labor spinners insisted the leader’s absence would allow other frontbench talent to shine.

Albanese had suffered a rocky start to the campaign and may have benefited from the circuit-breaker brought by his seven-day isolation. Labor’s reconfiguration may have been an attempt to make a virtue of necessity, but arguably it worked.

In his place, established names such as Penny Wong, Jim Chalmers, Kristina Keneally and, to a lesser extent, Labor’s deputy leader Richard Marles took more public profiles. Marles subsequently had his own isolation experience after contracting COVID.

Also prominent were the official campaign spokespeople, Jason Clare and Katy Gallagher. Clare in particular has demonstrated an ability to land a political blow, and played a strong supporting role as warm-up man and attack dog at Labor’s campaign launch in Perth last weekend.

However, one of Labor’s most popular and senior figures, Tanya Plibersek, has been much less prominent in the campaign so far. Her absence has not escaped the attention of the Coalition, nor the media. As an effective communicator, Plibersek has clearly been under-used so far in this campaign – especially given her popularity and profile.

At the time of publication, that looked to be changing as Plibersek attended a campaign function with Albanese. But she remain under-utilised.

Within the minor parties and independents, the leaders - such as Adam Bandt, Pauline Hanson, and Clive Palmer - tend to be the only ones garnering much of the national media spotlight. To some extent, this reflects the fact they are not prospective parties of government. And with the exception of Bandt, they are also not realistic propositions for seats in the House of Representatives, where government is formed.

Clearly the 2022 election could change that to a degree if some of the “teal” independents are successful, although by definition, independents speak only for themselves.

Just over a fortnight from now, the effects of these wider frontbench contributions – good and bad – will be matters for the voters to decide.

For voters, getting a better sense of the people and capabilities being offered by each of the prospective parties of government remains an important, if under-appreciated, aspect of our election contests.

Mark Kenny does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.