On vacation in Tel Aviv, former American test pilot Kaz Zemeckis spots something falling in the sky: a MiG-25 Foxbat, the Soviet Union’s most advanced fighter plane, seemingly shot down over Israeli airspace. The pilot of the plane is Alexander Vasilyevich Abramovich, known as Grief, and he’s willing to defect to America, offering the Foxbat as enticement. Soon, Kaz is accompanying Grief to Area 51, where the two pilots work to disassemble the MiG-25 and incorporate its secrets into the new American F-15 Eagle. But Grief has an ulterior motive, which will pit the two pilots against each other.

A cutting-edge jet. Two ace pilots from opposite sides of the Iron Curtain. A race between US and Soviet agencies to gain the upper hand in the Cold War. These are the elements of Chris Hadfield’s second novel, The Defector, a technothriller whose accuracy is vouchsafed by Hadfield’s storied career as a test pilot and astronaut. These are also the components of Firefox by Craig Thomas, a novel first published in 1977 and made into a film of the same name. Both Firefox and The Defector draw inspiration from the real-life story of lieutenant Viktor Belenko, who landed a Foxbat in Hokkaido, Japan, on September 6, 1976, defecting to the West and giving the Americans their first chance to examine the MiG-25 up close.

The Defector takes place in 1973, on the cusp of the Yom Kippur War, with Grief landing at Tel Aviv’s Lod Airport days before the attack by Egyptian and Syrian forces. Israeli prime minister Golda Meir sees the purloined MiG-25 and its pilot as leverage to prompt US president Richard Nixon to swiftly resupply her country. A crash is staged, a story put out that the MiG-25 was destroyed and Grief killed. Kaz, who flew against earlier MiGs in the Vietnam War before losing an eye in a test flight, is enlisted to help escort the plane back to the US and assist with the US Air Force’s comprehension of the MiG-25’s design. While the two pilots fly together and feel each other out, Soviet cosmonaut Svetlana Yevgenyevna Gromova is readying for the Apollo–Soyuz mission, which will bring American and Soviet spacecraft and their crews together in a gesture of goodwill. While in Las Vegas, Svetlana spots Grief, recognizing at once that something is amiss. Why is a Soviet pilot hanging around Caesar’s Palace? Svetlana and Kaz are characters in Hadfield’s previous novel, The Apollo Murders. Like that book, The Defector mixes history and fiction with period-accurate technological detail.

The dogfighting sequences in the book have the ring of authenticity. Hadfield, not surprisingly, shines when describing the physical effects of supersonic flight on the body, from the clenching of leg muscles (to keep blood flowing to the brain) to how a pilot could work the controls with an injured leg. The characters, though, are portrayed with less insight and care than the description of their limbs. The loss of Kaz’s eye might serve as an obstacle to his reinstatement as a pilot, yet he somehow breezes through the vision test. “You’ve only got one peeper, Kaz,” the flight surgeon tells him, “but it’s a beauty.” Likewise, Kaz’s girlfriend, Laura, is quickly shuffled aside when his mission begins. Part of this is the required relentlessness of test pilots, whose very occupation revolves around overcoming obstacles which would defeat the ordinary human. But there are no worthy obstacles, no cost, nothing sacrificed.

Grief, once his true mission is revealed, poisons a dog, a scene which Hadfield bizarrely renders from the hapless canine’s point of view. The Soviet pilot also garrottes a homeless man to rid society of someone he deems a parasite. A flashback shows Grief, then known as Sascha, doing the same to his own father:

Sascha kept his silence and evaluated what he saw. Bloodshot, unfocused eyes above a red-veined, swollen nose. A slack, unfit body thick with fat and a bulging drunkard’s belly.

Not my father, Sascha thought. A lowlife thing. Filth. Scum. His right hand was in his pocket.

The scenes glide over the man’s pathology. Villainy for villainy’s sake.

For a book set at a key moment during the Cold War, The Defector offers little historical perspective. Real-life characters are trotted onstage merely to be recognized. Golda Meir chain-smokes; Leonid Brezhnev schemes against the US; Henry Kissinger pushes papers. One could credibly portray Kissinger as a war criminal or an effective statesman or a Nixon toady more interested in celebrity than in world peace. But he’s included in The Defector as an empty signifier, like a Motörhead T-shirt worn by the tough kid on a sitcom.

The few non-white characters fare the worst. The proprietor of a Mexican restaurant proudly proclaims, “Fresh tortillas, I make them myself in the back!” A Navajo Air Force captain smiles, broadens his smile, smiles easily, smiles again, smiles even wider, and smirks, all within the space of six pages. The same character mentions his father’s service as a World War II code talker but offers no opinion on the government’s use of the desert as a test site for world-destroying weaponry. And when Mexican president Luis Echeverría is flattered and bamboozled by Brezhnev, he “smiled again, so widely his eyes crinkled behind his tinted glasses” and boasts that “Mexico’s tequila must be even more world-famous than I thought, General Secretary!” Such grinning subservience among Mexican and Indigenous characters would be reproachable in a book from 1973, let alone from 2023.

In style, Hadfield hews to the James Patterson formula: short chapters, a great many one-sentence paragraphs. The book is peppered with exclamation marks, seventeen in the prologue alone. The whiz-bang-ness of the The Defector’s construction doesn’t offset its rickety plot, which hinges on the American government giving a Soviet defector nearly unrestricted access to the most top-secret air base in the country. Could this happen in real life? Of course. But it eats away at the book’s verisimilitude and gives the characters little to overcome.

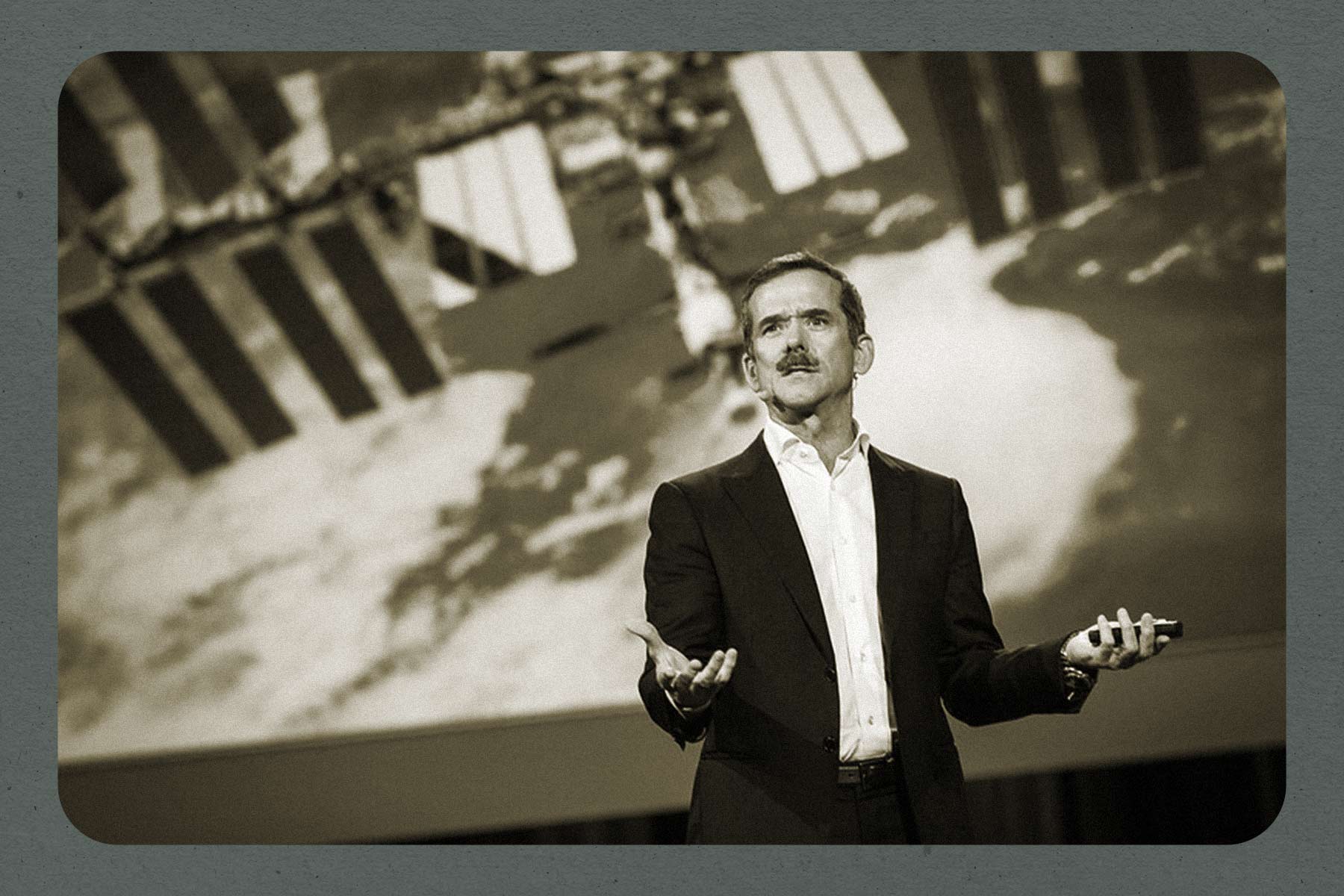

The son of a pilot, Hadfield moved from a middle-class Ontario childhood to the Canadian military, eventually becoming the country’s most renowned astronaut. “A veteran of three space flights,” the book jacket proclaims, “he served as capsule communicator—CAPCOM—for 25 Shuttle missions, as NASA’s director of operations in Russia, and as commander of the International Space Station.” He flew as a test pilot for the US Air Force and the US Navy, and as an RCAF fighter pilot. Not many on earth—or in orbit—have credentials even close to his. He has also earned celebrity beyond most astronauts or pilots. The YouTube video of Hadfield singing David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” while playing a Canadian-made Larrivée guitar aboard the ISS has 53,000,000 views and counting. He’s worked with Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Virgin Galactic, hosted two TV series, and given a popular TED Talk. Hadfield’s public image is of a champion of science with a nerd-culture streak, part Neil deGrasse Tyson, part Neil Patrick Harris.

The celebrity novel must be a boon for publishers constantly fighting for product discoverability. Here are authors already blessed with name recognition, whether from film (Sean Penn), television (Pamela Anderson, William Shatner), fashion (Naomi Campbell), politics (Hillary and Bill Clinton), or high-profile government service (James Comey). In Hadfield’s case, he positions himself less as a celebrity than as his own technical adviser, encouraging comparisons with former Navy SEAL turned author Jack Carr, whose praise adorns The Defector’s back cover. While the drawbacks of the celebrity novel are obvious—it doesn’t need to be well written (or even authored by the celebrity it’s attributed to)—its literary virtues are harder to pin down. Someone with extraordinary life experience yet who retains the common touch could, theoretically, draw on that experience to write about an aspect of life typically closed to the average person. Given his résumé and cultural pursuits, Hadfield would seem uniquely situated to do just that.

Hadfield’s first book, the nonfiction bestseller An Astronaut’s Guide to Life, opens with a pretty and arresting sentence: “The windows of a spaceship casually frame miracles.” The book, with its mix of technical detail, self-help philosophy, personal anecdotes, and offbeat humour, offers a glimpse into Hadfield’s mindset. He writes that, at the age of nine, he consciously decided to become an astronaut, framing every decision in terms of that goal, from what to eat to how to study. While Hadfield admits this pursuit left his wife to raise their children practically alone, there’s little time spent on regrets, no acknowledgement—at least not in the book—of missing out. At times, Hadfield inadvertently sounds like Tracy Flick from Election, an overachiever not only willing to sacrifice for his goals but to breeze over the trade-off.

There’s little insight into human beings in The Defector. People fly, kill, scheme, and grin through 340-odd pages without much in the way of motive. Some may chalk this up to the subgenre Hadfield writes in: the technothriller, after all, isn’t known for three-dimensional characterization. Yet in 1984’s The Hunt for Red October, arguably the most famous book in that peculiar canon, Tom Clancy’s characters have histories, interests, sex lives, and quirks of personality, from submarine captain Marko Ramius’s Lithuanian heritage to CIA analyst Jack Ryan’s injured back and to sonar operator Ronald Jones’s love for classical music. Contrast this with The Defector, where Grief claims to be Jewish to get preferential treatment from the Israelis. Is Grief actually Jewish, and does this affect his touchdown in a Jewish state on the eve of war? Or is it simply a chess move? It doesn’t matter to the mission, and Hadfield doesn’t explore it.

The Defector is a turgid, derivative, and carelessly written Cold War thriller rife with the prejudices of the era, from murderous Russkies to heroic American servicemen and their admiring wide-eyed girlfriends. While the characters share some of commander Hadfield’s knowledge and achievements, none shares the depth of his public persona. Kaz, Grief, and the rest have no interest in music or humour. To them, it appears, every moment outside the cockpit is wasted. The book shares this disdain for human interaction: when it sticks with dogfighting or satellite photography, it’s engaging, yet there are far too few of those moments. Given Hadfield’s accomplishments, I expected a novel that would approximate his science-with-a-humanist-face persona, an adventure tale populated by driven characters who nevertheless take an interest in culture. But The Defector is inert and clunky, a thriller with no thrills, a historical tale with no sense of history, peopled by characters with no character. For a celebrity novel, it shows little awareness of what made the author worth celebrating in the first place.