Gryphon entered one of their busiest periods five decades ago this year. The release of not just Midnight Mushrumps but also Red Queen To Gryphon Three found them reaching a bigger audience than before, aided by a North American tour with Yes. Founding members Brian Gulland, Graeme Taylor and Dave Oberlé recall those early years, and explain why they continue to champion their unique blend of medieval, classical and prog to a highly appreciative audience.

In the history of prog, there’s never been a band quite like Gryphon; and in the history of Gryphon there’s never been a year like 1974. Over 12 months, the group released not one but two fantastically ambitious albums; they also embarked upon a spectacular North American tour as the opening act for Yes.

Formed two years previously, the band’s genesis went back even further. Co-founding guitarist Graeme Taylor was nine when he first heard The Beatles, and describes the feeling as “like a cannonball [that had] hit me.” His parents promised to buy him a guitar; and, on Christmas Eve, “I woke up in the middle of the night and went halfway through the instruction book by about five in the morning. From then on, I was just fanatical about this instrument.”

He met fellow co-founder Richard Harvey at Tiffin’s boys’ school in Surrey. Not only did they share a number of interests, but they were both also involved in ensembles inspired by medieval and Elizabethan music. A few years later, Harvey encountered Brian Gulland while both were studying at the Royal College Of Music, and soon the trio began playing together.

Gulland was also young when his journey into music began. At eight, he enrolled in the Canterbury Cathedral Choir, where he enjoyed “five years of the most fantastic musical training.” During the first term, he recalls, “We were allowed to sit up on the lockers and watch the orchestra rehearse. I became inveigled by the deep farting noises of the bassoon.”

However, during his second year at the Royal College he decided to leave – much to the shock of his teachers and peers. “They were absolutely horrified, because nobody leaves; you have to fight to get in there. ‘What do you think you’re going to do, then?’ ‘Well, sir, I’ve got these vague ideas about playing Hammond organ in a rock band.’”

It was Harvey who persuaded Gulland to invest in a different instrument. “He came rushing up to me and said: ‘Come on, you’ve got to buy a crumhorn.’ I said, ‘What the hell are you talking about?’” He soon found out.

The band’s original incarnation was completed by percussionist Dave Oberlé. “I’d been a rock drummer,” he explains, “and to suddenly be confronted with all these very strange instruments, it was a question of how I was going to adapt.”

We used sit on the bed composing. We never really wrote it down… We’d work for half an hour then go down to the studio to record it

Graeme Taylor

Oberlé had been another early starter. At 12, his parents bought him a snare drum and he was soon playing in local rock bands. He formed a group of his own, Juggernaut, “playing quite heavy rock with proggy influences.” When Taylor, Gulland and Harvey recruited him, it was, he says, “a baptism of fire” – but it wasn’t long before he settled in.

The quartet were playing local folk clubs when Transatlantic Records talent scout Laurence Aston approached them. “It didn’t take very long for him to spot us,” says Taylor, “because we were unusual. We suddenly found ourselves with a recording contract in a makeshift studio, making our first album.”

Gryphon’s self-titled debut, released in June 1973, caused quite a stir with its fantastical blend of medieval and modern instrumentation. “Suddenly we became a household name,” recalls Taylor, “big pictures, centre-spreads; everyone knew who Gryphon was.”

Transatlantic’s press officer, Martin Lewis, was a key factor in their raised profile, too. “He was an absolute genius,” affirms Oberlé, “mad as a box of frogs, but a great marketing man.” It was through Lewis’s efforts that Gryphon became the first band to be played on all four BBC radio stations in the same week. Yet their biggest success was still to come.

During 1974 they released two further albums of startlingly inventive music – Midnight Mushrumps and Red Queen To Gryphon Three. By now, bass player Philip Nestor had joined. Both sets were recorded at the Chipping Norton Recording Studio in Oxfordshire, engineered by Dave Grinsted, the mastermind behind Caravan’s In The Land Of Grey And Pink. Musically, however, the two Gryphon records were put together on the fly.

It was shot in the middle of the night… if you look at the sleeve closely, you’ll see bright red noses because we were absolutely freezing

Dave Oberlé

“It was highly irresponsible in retrospect,” says Gulland. “These days you wouldn’t do it. But yes, we didn’t have any of that ‘getting it together in the country’ in a cottage for months. We went in and we cobbled together bits and pieces as we went.” This organic approach was made easier by the studio’s live-in accommodation and 24-hour access.

“We used to go up into Brian’s room,” recalls Taylor, “just sit there on the bed composing. We never really wrote it down, or if we did it was on the back of a fag packet. We’d work for half an hour and then go down to the studio to record it – we’d get Dave Grinsted up.”

“We were pretty adept at interpreting and performing each other’s material,” adds Gulland. “We thought, ‘Oh, this is a good challenge. I need to practise this for 30 seconds.’ Then we’d try and record it. There was some manuscript paper flying around as well as the backs of envelopes.”

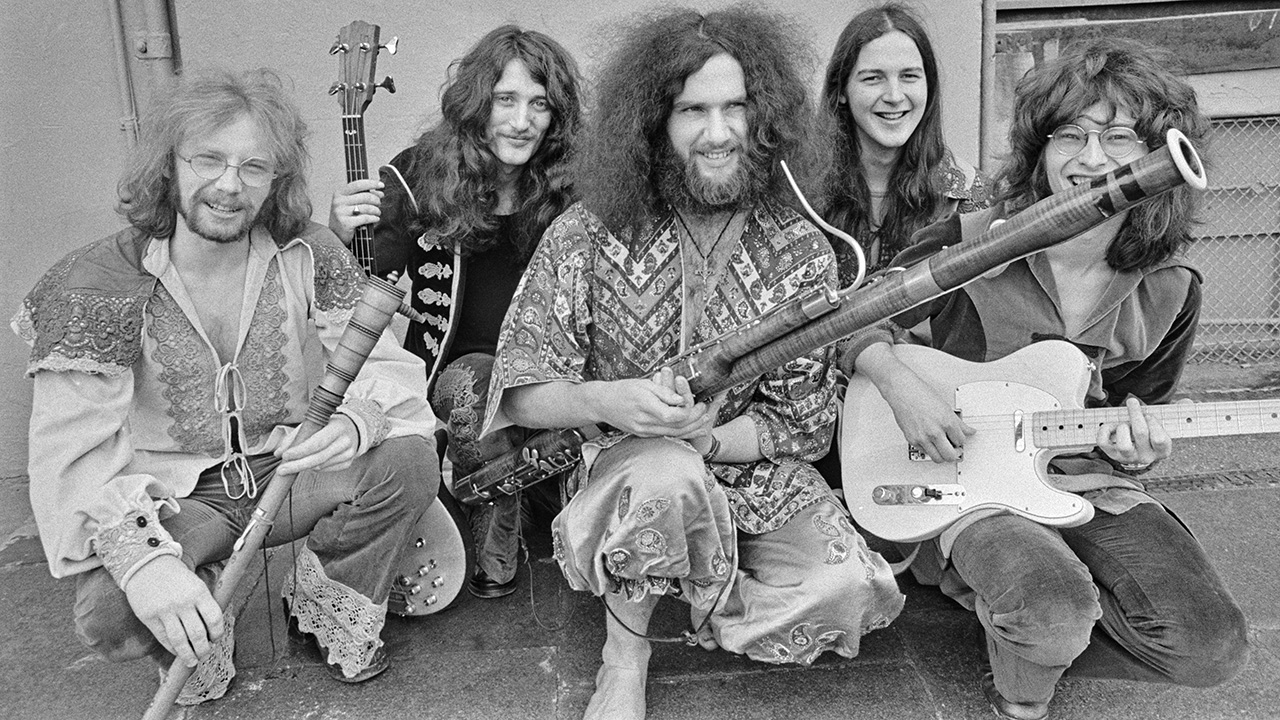

The atmosphere of spontaneity was clearly inspiring and resulted in some beautiful and intricate material. The free-wheeling spirit even extended to the Midnight Mushrumps cover. “It was actually shot in Windsor Great Park in the middle of the night,” explains Oberlé, “which is why, if you look at the sleeve closely, you’ll see bright red noses because we were absolutely freezing.”

The flamboyant clothing they wore for the shot also came from a surprising source. “We’d stolen lots of costumes from the National Theatre wardrobe and carted them into the park,” says Taylor. “I remember making the crêpe-paper mushrooms with chicken wire and lots of old newspapers soaked in gum.”

The Yes Album blew my socks off. Soon there was a kind of mutual admiration society going on between the two bands

Brian Gulland

Released in April, Mushrumps featured five original numbers, plus a cover of the traditional Ploughboy’s Dream. Fleshed out by Nestor’s pulsing bass, the band sounded even more polished and adventurous than on their debut. The title track – an intricate 19-minute suite – was partly adapted from music they’d composed at the request of renowned theatre director Peter Hall, to accompany a production of Shakespeare’s The Tempest.

That led to another first for Gryphon: they became the first rock band to play a live gig at London’s historic Old Vic Theatre; they remain part of a select number of musical artists to have played there. “We had Ivor Cutler supporting us,” remembers Gulland, “Jon Anderson, Steve Howe and Chris Squire of Yes came along, too.”

Gulland had formed a friendship with Yes a few years previously. He recalls seeing them play at the Roundhouse in Dagenham: “My cousin said, ‘Brian, I think you’d really like this band.’ So we jumped into his Austin-Healey Sprite and whizzed up to this little club. They’d just brought out The Yes Album, and it blew my socks off. Soon there was a kind of mutual admiration society going on between the two bands.”

It was a connection which would soon prove fateful. But first, Gryphon returned to the studio to work on third record Red Queen To Gryphon Three. “We thought of that as our concept album,” Taylor remembers, “loosely hung on a game of chess. The approach to recording was much the same.”

Consisting of four extended tracks, each a multi-segmented masterpiece of astounding variety, Red Queen was destined to become a cult classic and remains one of their most popular albums, even now. Given the extraordinary standard of playing across a whirlwind of sonic twists and turns, it’s not hard to understand why.

In terms of the size of the gigs, it was comparatively small… probably 10 or 11,000

Brian Gulland

At the recommendation of fellow Royal College alumnus Rick Wakeman, Gryphon scored a new manager, Brian Lane, and soon found themselves supporting Yes on their 1974 North American tour. “It was absolutely spectacular,” says Oberlé of the experience.

Gullard adds: “33 gigs in 38 days with a plane-hop in between each one.” The frantic schedule took some adjusting to, as the band were ushered between soundchecks, gigs, hotels and airports over and over again.

“You didn’t know where you were,” remembers Taylor – and it wasn’t only the pace that was challenging.

“I think the first place that we landed was Madison, Wisconsin,” Oberlé says, “and I distinctly remember walking into the gig, looking around and thinking, ‘My God, I’ve never seen anything quite like this!’ You suddenly thought, ‘We’re going to be playing here in front of thousands of people.’”

The Dane County Coliseum – now known as Veterans Memorial Coliseum – is part of a multi-venue complex used for sporting events and expos as well as concerts. Gulland recalls that the main arena where they played was a huge basketball arena, which “looked like a UFO from the outside. I think in terms of the size of the gigs, it was comparatively small. It was probably 10 or 11,000-seater, but it looked enormous to us.”

Despite the schedule, the band still found time to relax, absorbing and recording music from the multitude of radio stations across the country. Taylor and Gulland even brought themselves ghetto blasters in Miami. “I got seriously into the Grateful Dead,” says Taylor, “listening with speakers held up on either side of my head.”

It became fashionable to not be able to play your instrument very well. Unfortunately, we weren’t bad

Graeme Taylor

Back in the UK, Gryphon continued their support tour with Yes and recorded another album, Raindance, the following year; but things weren’t quite the same. Taylor left shortly afterwards, and the band recorded one final album, 1977’s Treason, before disbanding in the shadow of punk.

“The whole thing just changed that fast,” says Oberlé. “We knew the writing was on the wall. Had Gryphon started a little earlier we might have survived. Yes and Genesis managed to get through it, but we hadn’t really gotten to that point.”

As Taylor neatly puts it: “It became fashionable to not be able to play your instrument very well. Unfortunately, we weren’t bad.”

There followed a lengthy hiatus until a surprise reunion in 2009, prompted by the discovery of a flourishing fan community. “A guy called Eduardo Mota started the website,” Oberlé explains. “We saw it had been hit by about 200,000 people. We thought, ‘Oh my God, there’s something going on.’ Otherwise, why would people bother?”

“We’d forgotten about ourselves by then,” adds Taylor. “We’d forgotten about Gryphon. It became evident that the rest of the world hadn’t.”

Fifteen years on, Gryphon are flying high with an updated line-up that includes Taylor’s daughter, Clare, on vocals and violin; reed player Andy Findon; and Rob Levy on bass. Although Harvey left to pursue other avenues, the new-look band are back on the road and are working on the studio follow-up to 2020’s Get Out Of My Father’s Car!

They’re clearly thriving, and Oberlé thinks he knows why: “There is still nothing quite like Gryphon – even now.”