After their infamous plot to destroy parliament was foiled, Guy Fawkes and his co-conspirators received one of the most severe judicial sentences in English history: hanging, drawing and quartering. According to the Treason Act 1351, this punishment involved:

That you be drawn on a hurdle to the place of execution, where you shall be hanged by the neck and being alive cut down, your privy members shall be cut off and your bowels taken out and burned before you, your head severed from your body and your body divided into four quarters to be disposed of at the King’s pleasure.

This process aimed not only to inflict excruciating pain on the condemned, but to serve as a deterrent – demonstrating the fate of those who betrayed the Crown. While Fawkes reportedly jumped from the gallows – which meant he avoided the full extent of his punishment – his co-conspirators apparently weren’t so lucky.

By dissecting each stage of this medieval punishment from an anatomical perspective, we can understand the profound agony each of them endured.

Torture for confession

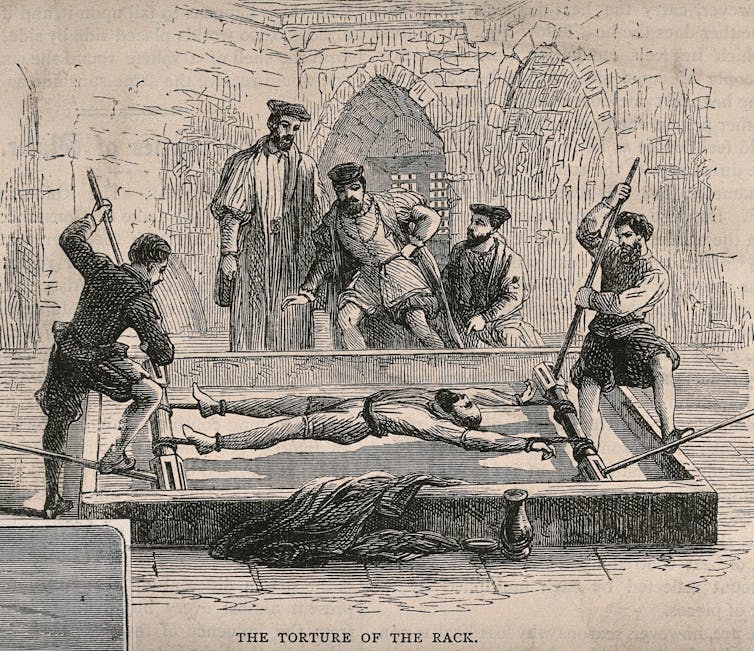

Before his public execution on January 31 1606, Fawkes was tortured to force a confession about his involvement in the “gunpowder plot”.

The Tower of London records confirm that King James I personally authorised “the gentler tortures first”. Accounts reveal that Fawkes was stretched on the rack – a device designed to slowly pull the limbs in opposite directions. This stretching inflicted severe trauma on the shoulders, elbows and hips, as well as the spine.

The forces exerted by the rack probably exceeded those required for joint or hip dislocation under normal conditions.

Substantive differences between Fawkes’ signatures on confessions between November 8 and shortly before his execution may indicate the amount of nerve and soft tissue damage sustained. It also illustrates how remarkable his final leap from the gallows was.

Stage 1: hanging (partial strangulation)

After surviving the torture of the rack, Fawkes and his gang faced the next stage of their punishment: hanging. But this form of hanging only partially strangled the condemned – preserving their consciousness and prolonging their suffering.

Partial strangulation exerts extreme pressure on several critical neck structures. The hyoid bone, a small u-shaped structure above the larynx, is prone to bruising or fracture under compression.

Simultaneously, pressure on the carotid arteries restricts blood flow to the brain, while compression of the jugular veins causes pooling of blood in the head – probably resulting in visible haemorrhages in the eyes and face.

Because the larynx and trachea (both essential for airflow) are partially obstructed, this makes breathing laboured. Strain on the cervical spine and surrounding muscles in the neck can lead to tearing, muscle spasms or dislocation of the vertebra – causing severe pain.

Fawkes brought his agony to a premature end by leaping from the gallows. Accounts from the time tell us:

His body being weak with the torture and sickness, he was scarce able to go up the ladder – yet with much ado, by the help of the hangman, went high enough to break his neck by the fall.

This probably caused him to suffer a bilateral fracture of his second cervical vertebra, assisted by his own bodyweight – an injury known as the “hangman’s fracture”.

Stage 2: Drawing (disembowelment)

After enduring partial hanging, the victim would then be “drawn” – a process which involved disembowelling them while still alive. This act mainly targeted the organs of the abdominal cavity – including the intestines, liver and kidney, as well as major blood vessels such as the abdominal aorta.

The physiological response to disembowelment would have been immediate and severe. The abdominal cavity possesses a high concentration of pain receptors – particularly around the membranous lining of the abdomen. When punctured, these pain receptors would have sent intense pain signals to the brain, overwhelming the body’s capacity for pain management. Shock would soon follow due to the rapid drop in blood pressure caused by massive amounts of blood loss.

Stage 3: quartering (dismemberment)

Quartering was also supposed to be performed while the victim was still alive. Though no accounts exist detailing at what phase victims typically lost consciousness during execution, it’s highly unlikely many survived the shock of being drawn.

So, at this stage, publicity superseded punishment given the victim’s likely earlier demise. Limbs that were removed from criminals were preserved by boiling them with spices. These were then toured around the country to act as a deterrent for others.

Though accounts suggest Fawkes’s body parts were sent to “the four corners of the United Kingdom”, there is no specific record of what was sent where. However, his head was displayed in London.

Traitor’s punishment

The punishment of hanging, drawing and quartering was designed to be as anatomically devastating as it was psychologically terrifying. Each stage of the process exploited the vulnerabilities of the human body to create maximum pain and suffering, while also serving as a grim reminder of the consequences of treason.

This punishment also gives us an insight into how medieval justice systems used the body as a canvas for social and political messaging. Fawkes’s fate, though unimaginable today, exemplifies the extremes to which the state could, and would, go to maintain control, power and authority over its subjects.

The sentence of hanging, drawing and quartering was officially removed from English law as part of the Forfeiture Act of 1870.

Michelle Spear does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.