Over a thousand years ago, a gentlewoman received a precious bundle of fine paper from her beloved Empress Teishi. She decided to write down her thoughts and opinions on anything that “moved and fascinated” her during her service at the Empress’s court.

This work, which collects witty repartee, poetic exchanges, anecdotes and much more, came to be known as Makura no sōshi, or The Pillow Book.

Little is known of the gentlewoman, not even her real name, though she was called Sei Shōnagon while serving at court. Sei is the Sinitic pronunciation of the first character in her family name, Kiyohara. Shōnagon was an official post once held by an unknown male relative of hers.

The custom of naming female court attendants with a combination of their family name and the position of a male relative conferred on them a degree of invisibility. But this did not stop them from passing on their voices and stories through writing.

Following one’s brush

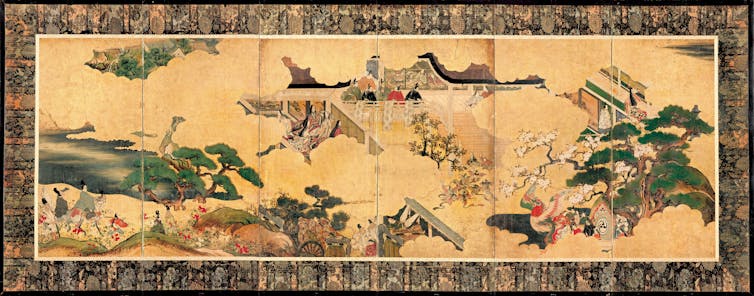

Along with Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji (early 11th century), which is considered the world’s first novel, The Pillow Book epitomises Japanese literature of the Heian period (794-1185).

Unlike the fictional narrative of Genji, however, The Pillow Book inaugurated a genre called zuihitsu which means “following one’s brush”. This is a free and spontaneous writing like the flowing movement of the writer’s brush. With this method, Sei Shōnagon constructs a miscellany different from the diaries written by other gentlewomen in the Heian period, whose records of their daily experiences mainly focused on personal romances.

The Pillow Book contains a wide variety of content. A section might simply list things, such as “Peaks – Yuzuruha Peak, Amida Peak and Iyataka Peak”. Other sections supply personal opinions, grouped under different topics. For instance, Sei Shōnagon tells her readers the best times in a year:

And how delightful it all is at the time of the Festival in the fourth month! The court nobles and senior courtiers in the festival procession are only distinguishable by the different degrees of colour of their formal cloaks, and the robes beneath are all of a uniform white, which produces a lovely effect of coolness. The leaves of the trees have not yet reached their full summer abundance but are still a fresh young green, and the sky’s clarity, untouched by either the mists of spring or autumn’s fogs, fills you with inexplicable pleasure.

Sei Shōnagon’s writing displays an extraordinarily heightened visual, aural and poetic sensibility. Even a mosquito can be amusing and comical in her description:

You’ve just settled sleepily into bed when a mosquito announces itself with that thin little wail, and starts flying round your face. It’s horrible how you can feel the soft wind of its tiny wings.

All this is exquisitely interwoven through the aesthetic of okashi, a word that repeatedly appears in her Pillow Book, meaning delightful, lovely, amusing or joyous.

Read more: Guide to the classics: The Tale of Genji, a 1,000-year-old Japanese masterpiece

Political marriages and aesthetic dominance

For most of Japan’s history, the Tennō (heavenly sovereign or emperor) held no actual power in state matters. Instead, whoever held the title embodied the supreme privilege of divine descent and figured in ceremonial functions.

During the Heian period, the Fujiwara clan dominated the court. Fujiwara no Yoshifusa (804-872) married his daughter Meishi (829-900) to Emperor Montoku (827-858). He thus became the grandfather of Emperor Seiwa (850-880), who ascended to the throne at the age of nine. Yoshifusa was appointed Sesshō (Regent) and de facto ruler in 866.

From that point, higher-ranked aristocrats competed to marry their daughters to the emperor in the hope of becoming, like Yoshifusa, grandfather of a future Tennō.

Given all that a favourable marriage could bring a family, a daughter was a valuable asset for realising a father’s political ambition. In order to make their daughters attractive to an emperor, higher-ranked aristocrats sought well-educated women from lower-ranked aristocratic families to cultivate their daughters’ tastes and sensibilities in poetry, music and calligraphy.

Imperial consorts were accompanied by their gentlewomen in the palace. They formed salons that competed for literary and cultural superiority, and ultimately for the emperor’s unfailing love.

Sei Shōnagon came from a household well-reputed for poetry. Witty and talented, she was chosen by Fujiwara no Michitaka (953-995) to serve at his daughter Teishi’s court.

Teishi and her family were at the peak of their power when Sei Shōnagon entered service. Michitaka was Kanpaku (Regent) and Teishi, his elder daughter, was Empress. Michitaka’s younger daughter was a consort of the Crown Prince. His son Korechika was the Palace Minister and expected to succeed the position of Regent after his father’s death.

But everything collapsed with Michitaka’s death in 995. His brother Michikane (961-995) took over as Regent for a mere seven days until an epidemic took his life. Their younger brother Michinaga (966-1028) then assumed power, and after series of political intrigues, his nephew and rival Korechika was banished from the court.

With the death of her father and her brother’s exile, Teishi’s position in the court was precarious. It was made worse when her cousin Shōshi (988-1074), the eldest daughter of Michinaga, was made an imperial consort and later an Empress whose rank equalled hers.

Teishi died in late 1000, two days after giving birth to her third child, Princess Kyōshi.

Elegant, blissful and amiable

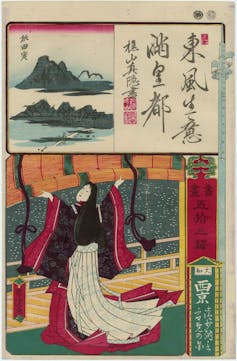

The upheavals affecting Teishi’s life at court are not recorded in The Pillow Book. In Sei Shōnagon’s written accounts, her Empress remains elegant, blissful and amiable. Her splendour never fades.

In one episode, Sei Shōnagon recalls the day Teishi moved to the house of a lower-ranked noble named Narimasa to give birth. Childbirth was believed to defile the palace, so imperial consorts and concubines would normally return to their families, but Teishi’s parents were both dead and her brother was in exile.

When Teishi’s attendants arrive at Narimasa’s house, they find the gate too narrow for their carriages. This unforeseen situation forces Sei Shōnagon and her fellow gentlewomen to alight and walk in view of many male courtiers with their hair in disarray.

From other historical records we know that Teishi’s move to Narimasa’s residence took place on the same day her rival Shōshi entered Emperor Ichijō’s harem. We can imagine the discomposure of Teishi and her gentlewomen. But Sei Shōnagon records only that when she complains to her Empress about the incident Teishi teases her with a smile. As Meredith McKinney, the English translator of The Pillow Book, succinctly puts it, Sei Shōnagon’s

gaze is determinedly, almost perversely, fixed on the delights to be found in court life; if sorrow momentarily clouds her sky, it is there only to provide the backdrop for some delightful event that relieves it with laughter.

In Sei Shōnagon’s account and for all subsequent readers of The Pillow Book, Teishi remains forever an elegant, jovial and amiable Empress who had no reason to grumble. In The Pillow Book, the gratitude and reverence Sei Shōnagon lavishes on the Empress Teishi at times borders on adulation. For Sei Shōnagon, Teishi is not only her patron but the one who really understands and appreciates her artistic abilities, as well as her companionship.

Sei Shōnagon often astutely recognises poetic allusions and references to stories in Chinese classics hidden in Teishi’s words. She is proud to be part of Teishi’s splendid court, and more importantly, she is happy to promote the Empress’s eminence.

The rivalry between consorts also affected their gentlewomen. Murasaki Shikibu, the most prominent woman author in Japan, remarks tartly that Sei Shōnagon

was dreadfully conceited. She thought herself so clever and littered her writings with Chinese characters; but if you examined them closely, they left a great deal to be desired. Those who think of themselves as being superior to everyone else in this way will inevitably suffer and come to a bad end, and people who have become so precious that they go out of their way to try and be sensitive in the most unpromising situations, trying to capture every moment of interest, however slight, are bound to look ridiculous and superficial.

As Empress Shōshi’s gentlewoman, Murasaki Shikibu was committed to enhancing the arts and establishing new aesthetics for Shōshi and her court. Her barbed attack on Sei Shōnagon is evidence of the ongoing contest of artistic sensibilities and taste.

Although Sei Shōnagon and her Empress had lost their status in the court, the blissful and untroubled aesthetic of okashi pervades The Pillow Book and gained enduring acceptance in the Heian court.

English Translations

The earliest English translation of The Pillow Book appeared in 1889 as an essay titled “A Literary Lady of Old Japan” in Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. In their translators’ notes, Theobald Andrew Purcell and William George Aston accentuate the purity, gentleness and femininity of The Pillow Book, regarding it as a product of “comparatively quiet and peaceful times”.

They selected six passages from this “curious medley” in the hope that this would offer their readers “some idea of the contents of this interesting work.”

In 1928, Arthur Waley (1889-1966) translated a quarter of The Pillow Book into English during the height of his fame as an orientalist and translator. Waley had taught himself classical Chinese and Japanese in 1913, while cataloguing the oriental collections in the British Museum. By 1919, he had translated many Chinese and Japanese poems.

From 1921 to 1933, Waley translated The Tale of Genji in six volumes. His rendition won instant critical acclaim and was a bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic. As The Pillow Book is usually considered a proper companion to Genji, it is no surprise that Waley would want to render both for English readers.

Waley adopts a free approach in translating both works. He chose not to translate the parts of The Pillow Book that were “dull, unintelligible, or so packed with allusion that it required an impractical amount of commentary”. For Waley, a translator must have “characters say things that people talking English could conceivably say”.

Although criticised for departing from the original, his beautiful renderings of The Pillow Book and other Chinese and Japanese classics had a vitality that appealed to English speaking readers.

Ivan Morris, a scholar and translator who was a great admirer and friend of Waley, translated The Pillow Book in 1967. Like Waley, Morris chose a free approach. He took the liberty of omitting some lists, such as place names and titles, which he considered insipid.

The latest translation by Meredith McKinney was published in 2006. Rejecting the prevailing tendency to use elegant or archaic sounding prose to render Japanese classics, McKinney embraces spoken, sometimes even colloquial English to let the readers hear the lively voice of Sei Shōnagon. It is the vividness of Sei Shōnagon’s voice and personality that McKinney attempts to convey, and I think she achieves her goal.

In any translation, the appeal of The Pillow Book is that, at Sei Shōnagon’s insistence, everything is charming and delightful. Through her observant eyes and exquisite writing, modern readers can follow her gaze as it moves among flowers, plants and trees, keenly observing insects, birds and, of course, people.

This effect is undimmed by the knowledge that life at court was also affected by rivalries and associated hardships. Readers can enter Sei Shōnagon’s idealised Heian court and listen in on conversations among courtiers on matters of love, wit or good taste. We can appreciate with her their richly worked and delicately scented garments, join their festivals and poetry contests, and feel some of the vibrant but transient beauty and colour of life in the service of an imperial consort.

Jindan Ni is the recipient of Japan Foundation Fellowship (2023-24) and is currently a visiting scholar at the National Institute of Japanese Literature.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.