Jason Featherston was in the final month of his 25-year career in the Texas Army National Guard when he heard the news. A text message: John “Kenny” Crutcher, a 45-year-old sergeant in the Guard, had died by suicide on November 12, 2021, leaving behind a wife and young daughter. “It’s still a shock,” Featherston says. “I think it just goes to prove everybody can be susceptible in the right circumstances, but it’s hard to believe.”

Crutcher, a North Texas native, was an “outstanding” soldier and infantry instructor, Featherston says. He suffered from post-traumatic stress from his military service in Afghanistan, according to his wife, but another factor at the time of his death was a military excursion closer to home: Operation Lone Star, Governor Greg Abbott’s massive, problem-plagued, and possibly unconstitutional mobilization of state troopers and military personnel to the U.S.-Mexico border. Crutcher had received permission to temporarily delay deployment to the border—so he could help care for a brother-in-law with a disability—but this permission was scheduled to expire when he took his life.

For Featherston, a 44-year-old who ended his service as the Guard’s senior enlisted advisor, a position at the heights of the 19,000-member force, Crutcher’s passing would prove a breaking point. Two other soldiers tied to Operation Lone Star had killed themselves around the same time; another would do so about a month later. Featherston had watched as the initiative—the latest and largest in a long line of state surges to confront refugees and migrants seeking entry to America—exploded from a deployment of about 1,000 in June to 10,000 in November. To pull this off, the state ordered Guard members, under threat of possible arrest, to separate from families and civilian jobs, sometimes with just days’ notice, for an assignment set to last a year.

Many requested exemption from deployment and were denied. Among them were hospital staff combatting COVID-19 surges in their local communities; police officers in understaffed departments; a federal agent who helps protect the country’s nuclear weapons; and Texans helping tend to ailing relatives, according to documents obtained by the Observer. “Texas was trying to get a number to go to the border; they didn’t care how they got it,” Featherston says. To add insult to injury, the Texas Military Department also announced, in October, that it would slash its tuition assistance benefit for soldiers by 54 percent. For Featherston, enough was enough.

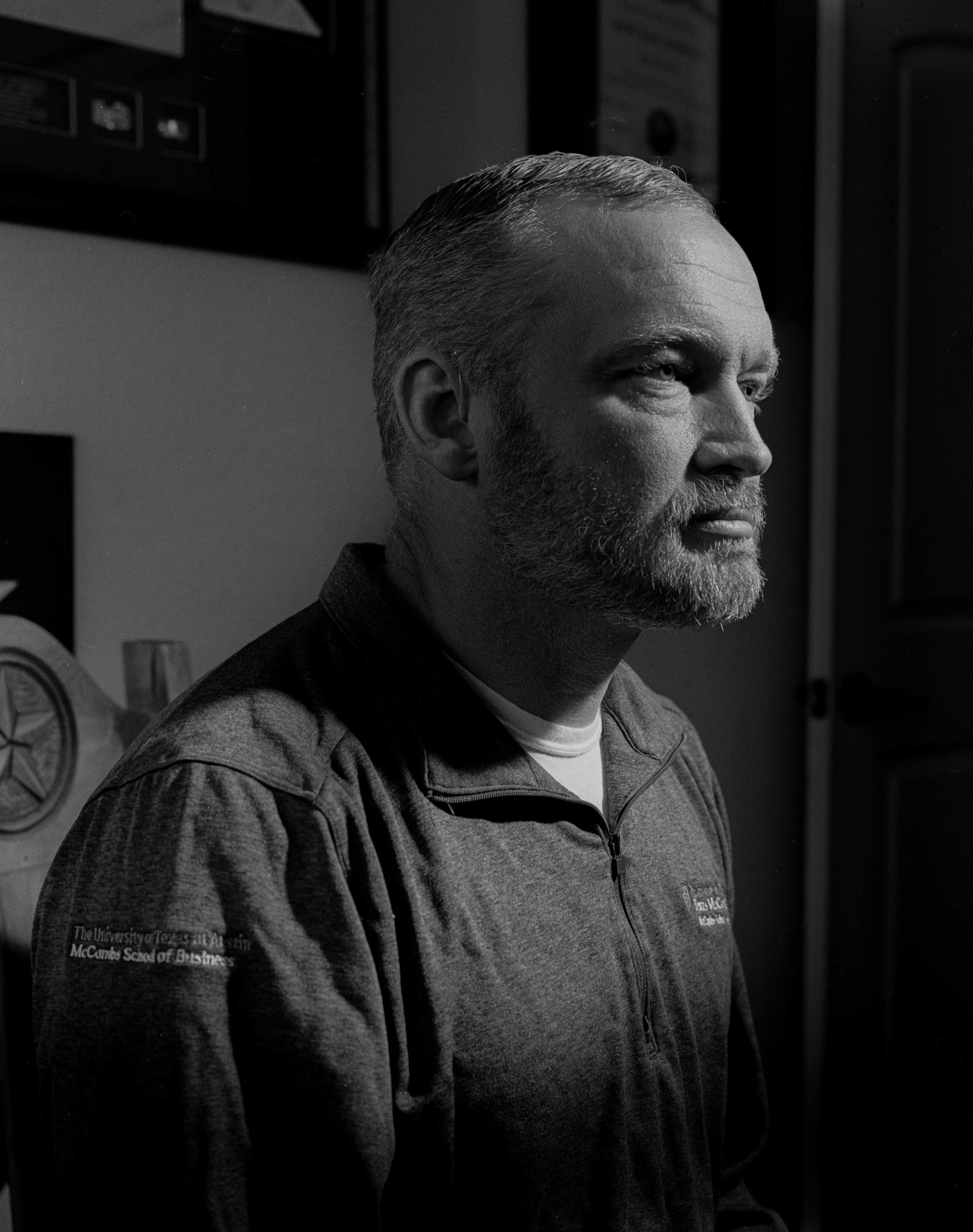

When I met Featherston on a February afternoon at Rudy’s Country Store and Bar-B-Q in Waco, a short drive from his house, he’d let his beard and wavy blond hair grow in—a symbol of his retirement. He was “protesting Uncle Sam,” he joked. He has an easy manner. As he discussed suicides and state incompetence, his teenage nephew filled out an application to work at the restaurant. Featherston works now for a large consulting firm, a job he got after finishing a master’s degree in May. Originally from the East Texas town of Athens, he enlisted in the Guard out of high school as a way to pay for college.

Just days after retiring, Featherston decided to reach out to a reporter at the Army Times who had covered the tuition assistance cut. Featherston was ready to speak on the record about what he saw as a disastrous operation, and he had documents to back it up. On December 23, the Army Times ran a story with the headline “Wave of suicides hits Texas National Guard’s border mission.” The article linked four suicides to Operation Lone Star and described widespread pay issues for soldiers deployed on the mission. Featherston was quoted extensively, arguing that the operation was a harmful and needless political stunt. A media frenzy, and an unwelcome scandal for Abbott, was born.

Ever since, Featherston has been deluged with messages from soldiers thanking him or reporting further problems at the border, like a lack of cold-weather gear and poor lodging. He shared a video on his Twitter account—a constant stream of info about the border operation—of soldiers packed “like sardines” in a sleeping trailer, which he says reminds him of the refrigerated trailers Guard members have had to load corpses into during the COVID-19 pandemic. He gets information quickly when new incidents occur, like another suicide attempt in late December or two accidental gun deaths in the subsequent two months. Soon, he began talking to reporters around the country.

The story spread from local outlets like the Houston Chronicle to the New York Times and CNN. A constant theme emerged from soldiers on the border, typically quoted anonymously due to fear of retribution. They were bored; the mission felt pointless. “We’re basically mall cops on the border,” one said, describing the daily duties of watching for migrants, then calling Border Patrol. Another described simply “staring” at Falcon Lake—a reservoir on the Rio Grande in Zapata County. “They sit on the border and look across the border,” Featherston summarizes, with a touch of scorn.

Featherston didn’t stop with the media. He reached out to the campaigns of Abbott’s challengers, including Democratic gubernatorial candidate Beto O’Rourke and GOP primary rivals. O’Rourke and Republican Allen West took special interest, calling him personally and making the issue central to their anti-Abbott messaging. “I know how the Texas Military Department works, I was at the top, and with the governor’s race going on, I knew that if I gave [the other candidates] information … that will force the governor to do something,” he says. Personally, Featherston supported West in the GOP primary but will vote for O’Rourke over Abbott.

Both the governor and the Texas Military Department have lashed back. In January, rather than reply to questions for a joint investigation by the Texas Tribune and the Army Times, the military department posted a statement saying it had been “the subject of scurrilous accusations by seemingly reputable media sources.” The department maintains that soldiers are playing an important role in repelling and helping incarcerate migrants and refugees. It also says most requests for exemption from deployment have actually been granted. The department adds that it is rapidly addressing equipment and lodging issues, and nearly all pay problems have been resolved.

Featherston agrees that things are improving for soldiers at the border; he just doesn’t think it would have happened without the pressure. “I’ve definitely gotten the agency’s attention,” he says. Had he never come forward, he believes, many more problems would remain unaddressed.

At Featherston’s spacious brick-sided house in the Waco suburb of Robinson, his three school-age daughters and a Great Dane fill the living room with energy. The walls of his modest home office are covered with commendations and mementos from the Guard. Here, he works his full-time job remotely and also wages his activist campaign, often late into the night. He’s a busy man.

“There are some times I’m super tired,” he says. “And I’ll get a random ‘thank you’ … and I’m like, all right cool—let me continue on this fight.”

.jpg?w=600)