Real estate is a hot topic in Canada. Most Canadians are acutely aware of how home prices and rents have skyrocketed in the last 15 years or so. In large cities, investor ownership of condos and houses has attracted the attention of policymakers and the public at large, prompting the federal government to crack down on foreign buyers.

While many are familiar with these urban real estate trends, few are aware of the restructuring of farmland ownership occurring in rural areas. Since 2014, we’ve been studying changing land tenure patterns in the Prairies, where 70 per cent of Canada’s agricultural land is situated.

Our research reveals three major trends — ongoing farm consolidation, increasing land concentration and expanding investor ownership of farmland — leading to growing land inequality. Like the transformation of urban real estate, who benefits from these changes is highly contested.

Investor interest in farmland

Investor purchases of farmland worldwide increased significantly as part of the global landgrab spurred by the food price spikes of 2007 and 2008. High food prices, a growing global demand for food and environmental pressures convinced many global investors that farmland was a safe bet in an increasingly volatile world.

As hedge funds, pension funds and wealthy individuals poured billions of dollars into farmland, researchers like us began to write about the financialization of agriculture — that is, the growing influence of financial players and financial motives over farming and food production.

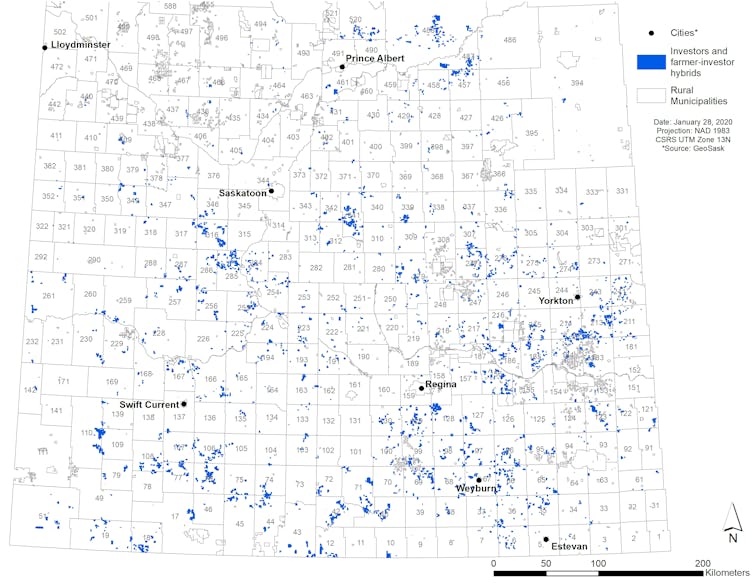

Our research found that investor ownership of farmland in Saskatchewan was negligible in 2002, but had climbed to nearly one million acres by 2018 — almost 18 times the size of Saskatoon. (A million acres is about 4,050 square kilometres). While Saskatchewan sought to tighten rules on farmland ownership in 2016, this seems to have done little to slow down the pace of investor acquisitions.

Robert Andjelic, an investor from Alberta, is now Canada’s largest landowner with 225,435 acres in 92 Saskatchewan rural municipalities. His company leases farmland to dozens of farmers and undertakes land improvements, such as clearing trees, brush and other natural habitat, as well as filling in wetlands in order to farm from corner to corner of every parcel.

Another major investor is Avenue Living, which has a foot in both urban real estate (as the owner of multi-family housing units across North America) and farmland, with a portfolio of some 83,000 acres.

As investors gobble up more land, there is growing unease among farmers. Investors argue they are helping farmers by relieving them of their assets and providing young farmers with access to land through rental agreements. Given that, on average, investors pay more for land compared to other buyers, these deep-pocketed buyers have undoubtedly contributed to the rapid increase of farmland prices.

In our survey of 400 prairie farmers, 76 per cent of farmers under 35 indicated that non-farmer investor activity has had a negative or very negative effect on the local farmland market. 83.2 per cent of older farmers indicated that investor activity has had negative or very negative impact on the local community.

Farmers also expressed unease about the growing economic clout of large farmers (over 10,000 acres) and mega-farms (over 30,000 acres) in the region.

Mega-farms keep accumulating land

Investors are not the only entities with vast landholdings. Some of Saskatchewan’s largest grain farms now own and control tens of thousands of acres. According to our research, Monette Farms owned some 63,000 acres of land in 2018, and farms much more than that with production sites in Montana, Arizona and Saskatchewan.

One Organic Farms reportedly operates on a land base of 40,000 acres, with the large majority of the land rented from Andjelic Land Inc., Saskatchewan’s largest investor-owner.

In-depth interviews with over 100 farmers in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba revealed many are deeply concerned about the environmental degradation wrought by big agriculture. Others argued these players out-compete locals for farmland and contribute little to local communities.

Why should city dwellers care?

Land inequality has significant implications for the vibrancy of democracy, the viability of rural communities and the sustainability of agriculture.

Accessing land is currently the biggest barrier for young and new farmers who want to get into farming and land prices continue to soar above what is justified by its productive value. At the same time, farm debt is the highest it’s ever been and the prairies are experiencing an emptying out of the countryside.

We should also be concerned about the financialized logic promoted by investors and mega-farmers, which seeks to extract monetary value from every square inch of farmland.

Given that agriculture is a significant contributor to Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions, doubling-down on this hyper-productive, fossil-fuel dependent model will only make it harder for Canada to meet its climate change commitment.

The question is: what kind of agriculture do Canadians want? Growing land inequality undermines the social, economic and environmental sustainability of agriculture.

Progressive agrarian and food movements propose a different future — one based on food sovereignty. This would entail equitable access to land for farmers, sustainable livelihoods and valuing farmland for its social and ecological worth, as well as its productive value.

As the climate crisis intensifies, there has never been a better time for urban and rural Canadians to work together to transform food systems.

Annette Desmarais receives funding from the Canada Research Chair Program and the Social Sciences and Humanities Council of Canada.

André Magnan receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.