With another snowy winter driving season here, the grieving parents of a young man killed when his truck flew off a snow-plowed bridge want drivers to realize they could face the same danger.

“I don’t want to see other people be injured or killed,” Craig Weber says of his son’s accident and other crashes the past few years in Chicago, Milwaukee and other wintry locales in which drivers slid up against snow that had been pushed by plows against highway barriers and were vaulted off elevated roads.

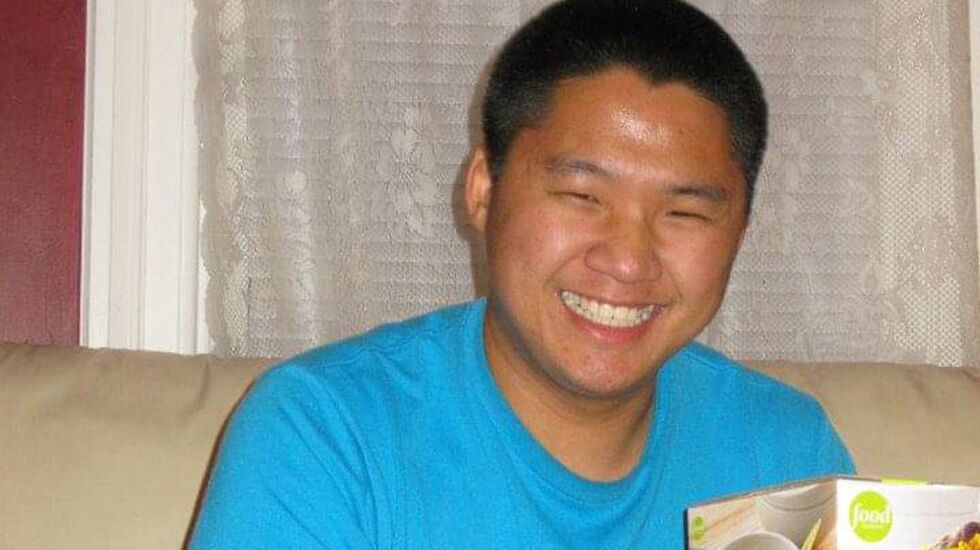

Christopher Weber was 27. The snow had stopped falling a full day before. He was making his morning commute over the towering Hoan Bridge on Interstate 794 along Milwaukee’s lakefront six years ago.

His pickup truck hit ice on the bridge and fishtailed. As he slid, the concrete barrier at the side of the highway didn’t keep him on the road. Plowed snow was packed hard and high against it, so the barrier acted like a snowboarder’s ramp. Weber couldn’t keep from riding up that ramp and vaulting off the bridge.

Weber, who just weeks earlier had started work at an information technology job he’d dreamed of getting, was killed when his truck landed on its roof 44 feet below.

“My thought was, ‘It’s a freak accident,’ ” says his father, who was a police officer for 41 years in southeastern Wisconsin. “Maybe it’s not so freakish.”

No government agency tracks these crashes. But a Chicago Sun-Times investigation has tallied 53 such snow-ramp crashes in cold-weather states since 1994, including five in Chicago and Milwaukee in a two-week span last year.

Among them, the Sun-Times reported, two people were killed when their car flew off a snow ramp on the Stevenson Expressway in Chicago. Two other vehicles vaulted off snow ramps on highways in Milwaukee.

Authorities responsible for snow removal in Illinois and Wisconsin haven’t done enough to ease this danger, Weber’s parents say.

“I would wish that they would change those policies so that doesn’t happen to another family,” says Deb Myrick, Christopher Weber’s mother.

Snow-ramp crashes tend to happen during winters marked by days of accumulating snow and below-freezing temperatures. Then, plowed snow piled high along concrete highway barriers can freeze.

By design, the slightly angled bottom lip of the barrier is supposed to nudge errant cars back onto the roadway. But plowed snow piled against it negates that protection.

Bridges, elevated roadways and highway ramps are especially prone to freeze, sometimes with “black ice” that drivers can’t see, creating a super-slick surface next to a hard, high snow ramp.

Deadly Stevenson Expy. crash

After days of heavy snow and repeated plowing, a Hyundai Veloster carrying two men and two women, all in their 20s, hurtled off the northbound Stevenson Expressway between Damen and Ashland avenues in McKinley Park on the Southwest Side on Feb. 12, 2021. It crashed into electric wires and a light pole, then plummeted 43 feet to a grassy area near Robinson Street.

It was near the spot where nine vehicles went flying off snow ramps on Interstate 55 during the especially harsh winter of 1978-1979, when the barriers were shorter. One person died.

In last year’s crash, driver Bulmaro Gomez, 27, and his front-seat passenger Griselda Zavala, 22, died, and two friends in the back seat were injured.

A toxicology test found alcohol in the driver’s blood. But an Illinois State Police accident reconstruction concluded: “The Hyundai continued forward over the wall due to the pileup of snow on the right shoulder.”

Police photos showed a wedge of snow packed against the barrier.

An Illinois Department of Transportation “snow and ice control” report filed a day after that crash said travel lanes and shoulders near Damen needed better attention, with “shoulders” underlined.

Zavala’s family has filed a lawsuit in the Illinois Court of Claims, accusing IDOT of failing to remove a known hazard or even to have warned drivers of the danger and seeking $2.2 million in damages. Under Illinois law, a “comparative fault” standard is used in deciding such cases. Even if the driver was impaired, the court also must consider other factors, like whether authorities ignored known hazards.

Four days after the I-55 crash, Kevin Ramos was northbound on the Illinois Veterans Memorial Tollway near the Lake Street overpass on Dec. 16, 2021, when he spun into plowed snow against the right-side barrier and sailed off. Miraculously, his Jeep Grand Cherokee landed wheels-down 22 feet below on Lake Street, missing other vehicles.

Ramos told the Sun-Times last February he’d barely noticed the snow along the 34-½-inch-high barrier along Interstate 355 and said the road itself appeared plowed and salted. He has since died of unrelated causes, according to family members.

The next morning, a 59-year-old woman driving on the Eisenhower Expressway was propelled off of snow piled against the inside concrete barrier separating Interstate 290 from the CTA Blue Line tracks after someone sideswiped her sport-utility vehicle. She landed next to the tracks, not on them.

An email that day to IDOT from Jeffrey Hulbert, the CTA’s vice president of safety, cited an “urgent need for swift action” and pleaded for state crews to remove the “launch ramp” that caused the woman’s car to fly over the barrier.

Also in February 2021, a 34-year-old man in Milwaukee plunged 70 feet in a Ford F-250 pickup truck that vaulted over a snow ramp on the Milwaukee Zoo Interchange of Interstate 94 and Interstate 41. Richard Oliver landed wheels-down on the road below and survived the fall, captured on a Wisconsin Department of Transportation video that went viral.

Eight days later, a 26-year-old woman driving a Hyundai Elantra in downtown Milwaukee vaulted over a snow ramp on the elevated Marquette Interchange but survived.

Family’s losing court fight

Drivers probably never think plowed snow on the side of a road poses any danger, Craig Weber says.

“For most drivers, as long as that main travel lane is plowed and salted, they don’t care what’s on the side,” Weber says.

He and Myrick battled Milwaukee County in court for years, unsuccessfully arguing that highway authorities were negligent in piling snow against the barrier and then failing to remove it. The parents noted that county workers trucked away the ramped piles of snow shortly after their son’s fatal accident — “too late,” Myrick says.

But an appeals court ruled against them, saying clearing that snow was discretionary, and the Wisconsin Supreme Court declined earlier this year to take their case.

“Milwaukee County created this condition, and they’re absolved of any liability,” Weber says. “There is what you and I would say is common sense, and then there is the law.”

WisDOT officials say they reviewed highway maintenance operations after the 2021 crashes.

“We communicated with the county highway departments and emphasized the importance of cleanup of these areas and getting to the snow piles as soon as possible. Since those discussions, there have been no similar incidents,” they say, and they “are reviewing plowing operation guidance in the highway maintenance manual to determine if changes are necessary.”

Differing snow-clearing policies

In Illinois, “IDOT continues to explore ways to increase safety and improve efficiencies during snow-and-ice events and throughout the year,” spokeswoman Maria Castaneda says.

The Illinois agency says it clears traffic lanes of snow so emergency vehicles can pass, then plows areas such as turns and shoulders.

After that, IDOT says it can conduct “packed-snow operations” to remove compressed snow using plows, snow blowers and other equipment, but that can be complicated and dangerous, involving lane closings and exposing crews to perilous conditions.

In an area that’s among the nation’s snowiest, around Buffalo, N.Y., more attention is paid to the dangers of snow ramps. Last month, crews south of Buffalo used heavy-duty blowers to avoid creating snow ramps after a monster snowstorm dumped 80 inches on southern Erie County.

County Executive Mark Poloncarz says they had a huge advantage, though: a ban on roadway travel beginning one hour before the first flakes fell. With no cars on the roads, crews were able to plow and collect snow. Much of that ended up in a community college parking lot, where two piles nearly five stories high remain four weeks after the storm.

To prevent snow ramps from forming, workers used heavy-duty blowers to blast the shoulders clear.

Two days after the storm, “You would not have recognized that a snowstorm had occurred on the elevated roadways because the snow was pretty much cleared,” Poloncarz says.

The sting of son’s loss

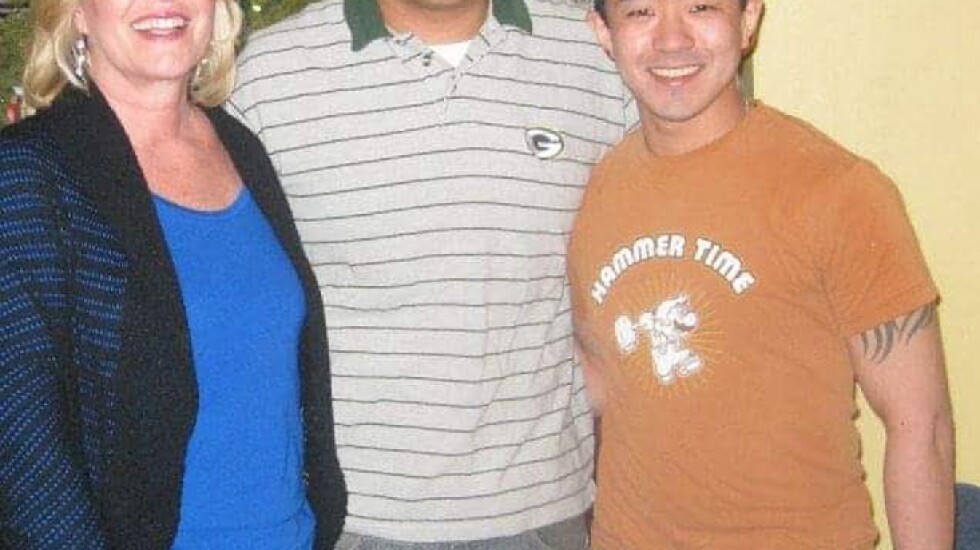

Six winters since Christopher Weber’s death, his parents remember the baby who arrived in the United States at O’Hare Airport when he was 41⁄2 months old, adopted, like his older brother, from South Korea.

Myrick, who’s since moved to Missouri, compiled a video filled with images of Chris blowing out birthday candles, playing at the beach, playing Power Ranger, sitting on Santa’s lap and in his football uniform, graduating from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and playing the guitar.

Myrick knew she’d never get an apology. But she had hoped she could testify in court about her son and what his death meant for those left behind. Then, the lawsuit was dismissed and their appeal turned away.

“I thought, even if we lost, I would beg them to watch the video in honor of his life,” she says. “He was needlessly lost.”