A long-lost Second World War spitfire flown by a pilot who was part of the “Great Escape” has been found almost entirely intact on a Norwegian mountain – 76 years after it was shot down by Nazis.

The discovery is the first time for more than 20 years that a substantially complete and previously unknown Spitfire from this period has been found anywhere in the world. Its pilot was captured and ultimately executed by the Nazis for taking part in the war’s most famous prisoner-of-war breakout, immortalised in classic movie The Great Escape.

Of substantial historical importance, the find highlights a normally ignored aspect of the Second World War – the RAF’s ultra-secret aerial wartime espionage missions.

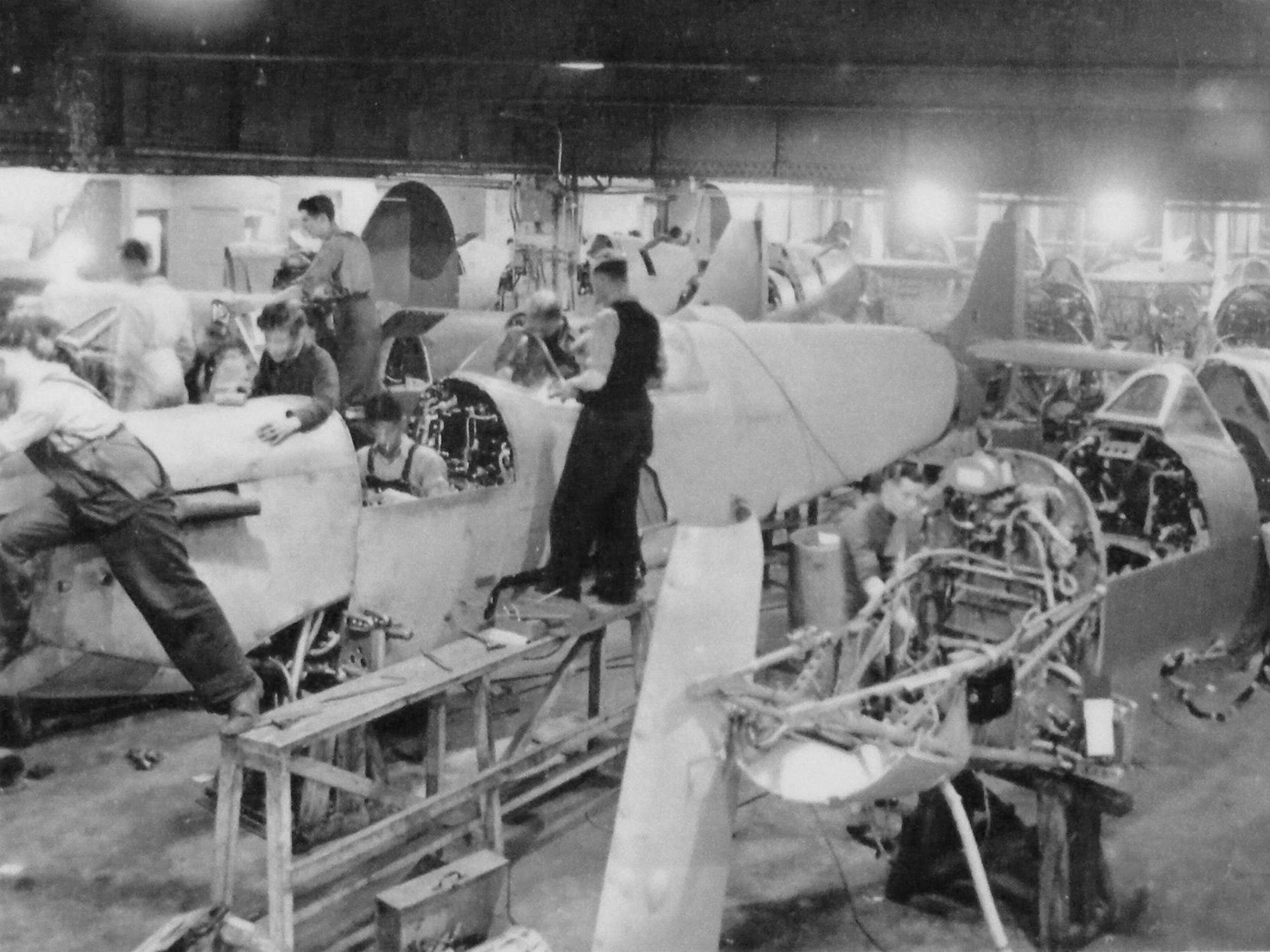

Between 1939 and 1945, more than 500 specially modified ultra-lightweight long-range Spitfires were built – mainly in Reading and Aldermaston, both in Berkshire. The planes were made for use by the RAF’s Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU).

They were sent on highly dangerous secret missions to photograph enemy ships, troop movements, manufacturing facilities, railways and dams. Unarmed, stripped of all their armour plating and armoured windscreens and without even a radio, they had extra fuel tanks – and had four times the range of a conventional Spitfire.

On average, each PRU Spitfire had a life expectancy of just 14 weeks. Many were shot down over the North Sea in the first three years of the war – and have therefore never been located. Others, flying at great height (up to 42,600 feet) were shot down over France and Germany in 1944 and 1945. But, because they crashed from a substantial altitude, they were almost always entirely destroyed on impact.

The substantially complete Spitfire discovered in Norway is therefore an extremely rare and unusual find.

After 11 months of detailed research, the long-lost aircraft was located and identified by a Sussex-based Spitfire historian and restorer, Tony Hoskins, with help and information from local people, on a mountainside, 56 miles southwest of Trondheim.

The location is remote – and normally covered by deep snow for 80 per cent of the year. Despite being mainly intact, the aircraft had to be extricated piece by piece from the bog in which it was submerged before being carried down the mountain.

The secret operation the plane had been involved in was typical of the thousands of similar missions the RAF’s PRU flew throughout the war.

Spitfire AA810 had taken off from Wick in Northern Scotland at 8.07am on 5 March 1942. Piloted by Scotsman, Alastair “Sandy” Gunn, it then flew 580 miles across the North Sea to Faettenfjord on the Norwegian coast. Gunn’s mission was to photograph the famous German battleship, the Tirpitz which was sheltering in that fjord.

Winston Churchill was desperate to keep an eye on the battleship, because she posed a potentially lethal threat to British arms supply convoys on their way to Russia.

Accurate intelligence on Tirpitz’s movements was therefore crucial to Britain’s efforts to bolster the Soviet Union’s ability to fight Nazi Germany.

Gunn’s secret operation was the 113th such mission to try to monitor the German battleship – and the first to be successfully intercepted by the Luftwaffe.

Because the round trip from Britain to Norway was around 1,200 miles, the Nazis believed that the British spy planes were incapable of clocking up that mileage without landing to refuel. They therefore wrongly convinced themselves that the British had established a secret airfield somewhere in German-occupied Norway, or even in neutral Sweden.

Shooting one of the British reconnaissance aircraft down would not only disrupt British military espionage – but might yield information as to where this imagined secret airfield was.

Spitfire AA810 was shot down by two Messerschmitt 109 fighters. An archaeological excavation of the plane has revealed it was hit by 200 machine gun bullets and 20 rounds of cannon fire. Before it hit the ground at around 20 degrees, its engine had stopped and its starboard side and nose and cockpit were both ablaze.

Because of its shallow angle of impact – and because the ground, on the side of a mountain, was covered in deep soft fresh snow – the aircraft survived relatively intact.

Gunn, who had facial and other burns, had succeeded in bailing out. Local Norwegian civilians found him and discussed with him the possibility of him escaping over the mountains to Sweden. But he did not know how to ski and it would have been a 110-mile long trek across very difficult terrain.

Gunn therefore decided against the idea – and made the fateful decision to surrender to the Germans. He then walked down the mountainside to a local village where German troops found him.

He was then flown to Oslo and then to Frankfurt, where he was interrogated by German military intelligence for four weeks.

Gunn was then sent to a POW camp, Stalag Luft 3 (in what is now Poland), where he participated in the Second World War’s most famous PoW breakout – the Great Escape (March 1944). So furious was Hitler over the escape attempt that he ordered that a majority of the escapees should be executed. Gunn was shot by Gestapo executioners in April 1944 – along with 49 other RAF fliers – including 11 Spitfire pilots.

The battleship Tirpitz survived until November 1944 when it was sunk by the RAF off Tromso, Norway.

Spitfire AA810 was discovered embedded in a mountainside peat bog. After careful excavation and meticulous on-site recording, its component pieces were carefully packed into boxes and driven back to the UK.

Around 70 per cent of the aircraft had survived the crash and the subsequent 76 years in a peat bog. Key parts of the fuselage and wings will now be reassembled and combined with parts from other Spitfires to ensure that by 2022 (exactly 80 years after it was shot down), AA810 will fly again.

Reconstruction work on the plane will start in Sandown, Isle of Wight, next month. It will be the first time ever that a wartime-crash-recovered PRU Spitfire will have been reconstructed to flying condition.

Excavating, recovering and reconstructing AA810 is costing at least £2.5m – and is being part-funded by a Cambridgeshire-based craft beverage distiller – Spitfire Heritage Gin (G&Ts were apparently the Spitfire pilots’ preferred tot) – and a Hampshire-based aerospace consultancy called Experience Tells.

“Rebuilding this iconic aircraft is a homage to Alastair Gunn and the other brave men who flew her,” said Mr Hoskins.

His research has revealed that in its 22-week operational life, the plane had at least seven pilots – including the Welsh champion jockey and 1940 Grand National winner Mervyn Anthony Jones, and the Indian-born English motor racing star – of partly Armenian-origin – Alfred Fane Peers Agabeg. Both lost their lives flying missions for the PRU, as did two of the others.

The archaeological excavation of Spitfire AA810 has also shed fascinating new light on how the German army searched the crashed spy plane for intelligence information.

They appear to have systematically removed all three F24 cameras and the negatives they contained – and also, in vain, combed the aircraft for documents and maps – items that PRU pilots never flew with.

The film stock Gunn and his PRU colleagues used on their secret espionage missions was produced by Kodak in Harrow, northwest London – but, in recent years, it has emerged that a Kodak factory in Switzerland appears to have been supplying the Germans with identical or similar stock.

A TV documentary on the discovery and recovery of Spitfire AA810 will be broadcast, as part of the Digging for Britain archaeology series, on BBC4 on Wednesday 28 November.

Mr Hoskins will publish a book (Sandy’s Spitfire) on the aircraft and its pilots in March next year, the 75th anniversary of the Great Escape, the event which led to the execution of Gunn.

Alongside the Spitfire restoration programme, he is also launching a groundbreaking education scheme to enable hundreds of 14- to 18-year-olds over the coming decades to start learning aircraft restoration engineering skills.

“The aim of the Spitfire AA810 restoration project is not just to ensure that this iconic aircraft flies again 80 years after it was shot down – but also to launch a longterm programme to ensure that 21st-century youngsters can begin to learn crucial aviation-related engineering skills,” said Mr Hoskins.

“The plane’s last pilot, Alastair Gunn, had been studying engineering before he joined the RAF – so the new education programme is being named after him.”

The Alastair Gunn Aviation Skills Program will be launched next year, initially as an integral part of the project to restore the aircraft.

Alastair Gunn was one of 74 PRU pilots who lost their lives on secret Norwegian missions during the Second World War.