In his Channel 4 series, Full English, artist Grayson Perry travels around England in a white van searching for an answer to the question: “Is there a viable version of England and Englishness that will feed my soul?”

What Perry discovers in his encounters with people from across the country, is a version of Englishness that draws on a subjective sense of local or regional identity, rather than a uniform idea of the nation.

For football fan Jay, England is first and foremost the borough of Lambeth. For grime musician Jaykae, England is Birmingham’s Small Heath, where he lives and finds inspiration for his lyrics. For fashion designer Pearl Lowe, England is evoked through dinner on a Somerset lawn.

Perry’s observations on regionalism (giving greater weight to viewpoints from people belonging to regions rather than the capital) chime with debates about what it means to be English. They are also in keeping with growing calls from politicians, cultural institutions and the public to give greater recognition to the contribution of England’s regions to the political, cultural and social fabric of the nation.

Full English confronts unease about English nationalism and the racism, chauvinism and the selective and nostalgic view of a national past that has often accompanied it.

Numerous articles, commentaries and opinion pieces have connected these views with the outcome of the 2016 Brexit referendum. At the same time, scholars and politicians have predicted a rethink of what it means to be English in response to the independence movement in Scotland.

Surveys show that younger generations are less proud to be English and the latest census data indicates that fewer people are identifying as English, opting for the more inclusive “British” instead.

The regionalism celebrated in Full English reflects cross-bench support in Westminster for strategies to overcome persistent geographical disparities in wealth and opportunity.

The government’s levelling up white paper promises to realise “the potential of every place and every person across the UK”, but its strategy of making regional areas compete for funding controlled by Whitehall has been criticised.

The Labour Party’s Brown Report puts forward ambitious plans to scrap the House of Lords in favour of a second chamber called the Assembly of the Nations and Regions. The report concludes:

The United Kingdom will only succeed economically, politically and socially if it harnesses the talents and listens to the voices of all its people, ensuring that no part of the country is left behind, ignored or silenced.

All the while, calls for more devolution (moving decision making out of London) in England are growing, with a new north-east mayor created as part of £1.4 billion deal announced in December 2022.

Victorian visions of the nation

Nineteenth century literature shows us that England and Englishness have long been interpreted through the lens of regional cultures and communities.

To modern debates, this writing provides valuable insights about the ways regional voices have been repeatedly sidelined, subjugated or overridden by decision makers at the centre.

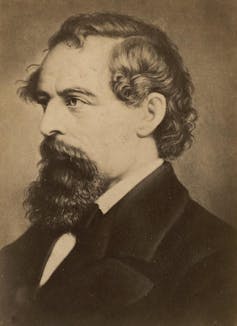

Charles Dickens is widely recognised as one of Britain’s greatest novelists but it is the geography of his adopted home, London, that is in sharpest focus in his work. His ambivalence towards “Englishness” can be seen in the extreme patriotism of John Podsnap from Our Mutual Friend, for example.

Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is perennially crisscrossing the moors of the Pennines familiar to her author. Settings like Thornfield Hall and Morton School are situated first and foremost by their remote regional locations, rather than in relation to the geography of a wider England.

This foregrounding of regional characteristics complicates the status of both these places because they are sites where Jane, as both school mistress and governess, is responsible for teaching an English education that takes for granted the unity and cohesion of the nation.

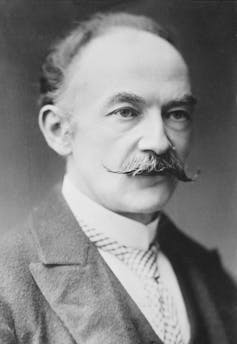

Thomas Hardy’s ‘partly dream country’

But the relationship between regionalism and national identity that Grayson Perry discovers in modern England has its clearest parallel in the writing of Thomas Hardy.

In Hardy’s Wessex poems, tales and novels, readers are immersed in a “partly real, partly dream country” that is both distinct from and connected to 19th century England.

Hardy’s blurring of fiction and reality sees that Wessex (his fictional county) is granted an importance and degree of autonomy beyond that normally afforded to real regional settings.

Nevertheless, readers are invited to construct versions of England and Englishness through the lens of Wessex.

Take, for instance, this extract from Hardy’s novel, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, where Tess and Angel Clare reflect on the journey of the milk they just brought to the railway station:

‘Londoners will drink it at their breakfasts tomorrow, won’t they?’ she asked. ‘Strange people that we have never seen … Who don’t know anything of us, and where it comes from; or think how we two drove miles across the moor to-night in the rain that it might reach ’em in time?’

In this passage, Hardy reorientates the power dynamics of the map, showing the dependence of the people in the capital on the frequently overlooked and stigmatised people of the region.

In this sense, Grayson Perry’s Full English is a modern take on the significance of regional cultures and communities described in 19th century literature. Perhaps such a timely celebration of regionalism has the capacity to provide a basis for the productive version of Englishness Perry seeks.

John Blackmore receives funding from the AHRC via the South, West & Wales Doctoral Training Partnership.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.