The 2019 Conservative manifesto promised to increase the UK’s GP numbers by 6,000 by 2024. That target will clearly not be met. In fact, the proportion of GPs working full time in England has fallen compared with last year, according to the latest figures from NHS Digital.

There were 26,706 permanent qualified GPs working in England in December 2022, down from 27,064 in December 2021. And if projections from the Health Foundation prove to be accurate, the shortfall is set to increase to around 8,800 GPs by 2030-31, equivalent to one in four posts being vacant. But is the UK unique among wealthy nations in suffering from a crisis in primary care?

It appears not. Australia has a GP shortage that is predicted to grow to more than 11,000 by 2032, with the demand for GP services increasing by 38.5% in that time. Likewise, Canada and New Zealand have similar GP workforce problems.

In New Zealand, half of its GP workforce intends to retire in the next decade. While Canada has seen a modest 1.2% increase in the number of family doctors, the demand for primary care services continues to outpace the supply of doctors.

In the UK, a quarter of all doctors are GPs, whereas it is one in three in Australia, and nearly one in two in Canada. Extrapolating from World Health Organization data, Australia and Canada have roughly similar numbers of GPs per head of population (12 and 11 per 10,000 population respectively), but the UK lags considerably behind (less than eight per 10,000 population).

However, international comparisons are difficult because how GPs are defined and what they do differs from country to country.

In the UK, the nature of general practice has changed considerably in the past two decades. British GPs deal with more than minor ailments.

In addition to triaging referrals to hospital specialists and providing health screening and vaccination services, they also manage patients’ chronic diseases (such as diabetes), which were previously handled by hospital specialists. They also play a key role in coordinating healthcare for patients in long-stay care facilities, such as nursing and residential homes.

British GPs are also having to care for more patients with complex health conditions because the population is ageing and many people have more than one chronic condition – known as “multi-morbidity”. One English study estimated that over a quarter of patients have two or more long-term conditions.

Having multi-morbidity is associated with increased health service use. These patients account for more than half of all GP consultations and hospital admissions. Multi-morbidity is also much more common in older populations.

A large Scottish study found that more than 80% of patients over the age of 85 years had multi-morbidity, and, on average, they had more than three long-term conditions.

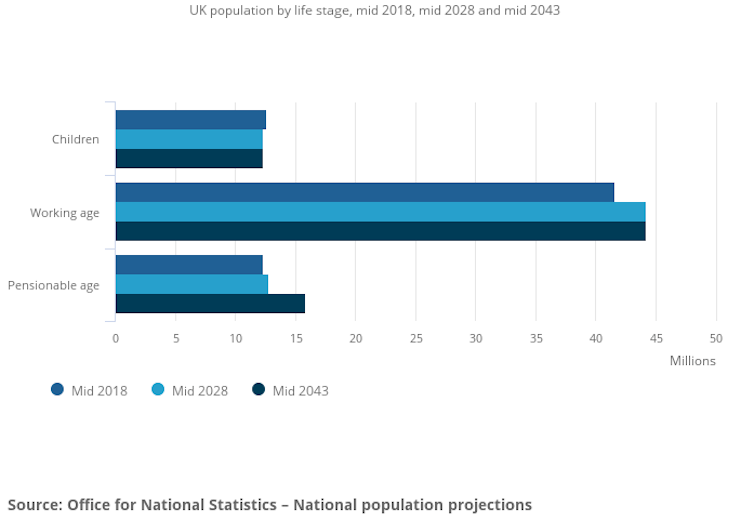

It is unsurprising that the demand for GP services has gone up over the years in the UK, and will continue to do so, as the proportion of the population that is elderly increases. The UK Office for National Statistics estimates that the proportion of people aged 85 years and over will almost double over the next 25 years.

With falling GP numbers, the pressure felt by GP services will continue to increase as demand outstrips supply.

The number of people of pensionable age is projected to grow the most

Reasons for leaving

So why do so many GPs leave the profession? One consequence of the high work pressures and long hours is burnout. This phenomenon is not unique to the UK and has been reported worldwide, with some estimates as high as one in three GPs suffering burnout. The pandemic has also had an impact on GP burnout worldwide.

Burnout and job dissatisfaction have been identified as key reasons for British GPs leaving the NHS. In one survey, three-quarters of British GPs reported their workload to be unmanageable or unsustainable.

Another UK study conducted in 2016-17 suggested that more than 70% of GPs reported severe exhaustion. Burnout was associated with spending more hours on administrative tasks, seeing more patients daily, and feeling less supported.

Australia and New Zealand have for some years been attractive options for British-trained GPs for numerous reasons. The current NHS climate and workload may be driving some doctors away from the UK.

One survey of UK-trained doctors in New Zealand found that 70% had relocated for a better lifestyle, due to poorer job satisfaction in the UK and disillusionment with the NHS. Doctors in New Zealand also had comparatively more leisure time than NHS doctors.

So what can be done?

How to keep GPs

To increase the number of GPs in the UK, sustained government funding and a long-term GP workforce strategy and plan are essential. To fix its recruitment and retention crisis, the UK needs to address the unhealthy work climate for GPs by improving support, reducing their administrative workloads, and tackling their patient workload intensity and volume, as well as long hours.

England is also trying some innovative schemes such as the “additional roles reimbursement scheme”, where networks of GPs are able to recruit additional staff such as physiotherapists, paramedics and pharmacists to augment their clinical teams and enable some tasks to be shifted from GPs.

However, the workforce for these roles is also in short supply, and some will need time and GP supervision to learn the skills needed to operate effectively in the community.

Trying to recruit more GPs or these allied health professionals from abroad is unlikely to succeed given the global shortage of both these groups of professionals.

Contrary to public myth, GPs generally also wanted more direct contact with their patients and valued the continuity of care – the loss of which has been cited as a reason why GPs leave general practice early. Public expectations will need to be managed, and negative media portrayals and criticisms of GPs are unlikely to help improve the worsening primary care situation.

Andrew Lee has previously received research funding from the National Institute for Health Research. He is a member of the UK Faculty of Public Health and the Royal Society for Public Health. He was previously a GP in Sheffield.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.