The Government’s pledge to build one million homes in England by 2020 could trigger the approval of hundreds of new quarries, as mining companies ride roughshod across cash-strapped local authorities, campaigners have warned.

While councils insist they will abide by planning rules to reduce the impact on communities of new extraction sites, activists claim many authorities are already struggling to cope with the number and complexity of applications.

The building industry’s demand for aggregate – sand and gravel – dictates the number of new pits local authorities have to establish, under rules contained in the government’s National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). Using market data from the South-west and South-east – two of the most mineral-rich regions in the country – six million tons of aggregate would be needed to build 100,000 homes a year – the equivalent of 100 new quarries.

Opponents of primary aggregate – material extracted from new pits – claim that local authorities are rushing through the approval of new sites without carrying out proper impact assessments.

In rural south Dorset, three quarry sites have been proposed close to the grave of T E Lawrence, the man immortalised as Lawrence of Arabia. Opponents say the pits are so close together that the 559 acres earmarked for extraction will effectively become a single super-pit – the largest in England.

Local people opposed to the quarries say that two of the sites have been “parachuted” into the county council’s mineral plan at the last minute.

“The sites have been identified following the adoption of the minerals strategy that sets out the vision, objectives and policies for meeting Bournemouth, Dorset and Poole’s mineral needs,” Dorset council said in a statement. “This strategy was prepared following consultation with residents, planners and the industry.”

Opponents dispute this. “Two of the sites have not featured in any previous iterations of the Dorset Mineral Site Plan, or the 2013-14 consultation period,” said Garry Thompson of the action group Frome Residents Against Mineral Extraction (Frame). “There is no evidence to support that an appropriate level of due diligence has actually been performed. The only conclusion that can be drawn is that these are cursory at best and almost entirely reliant on desk-based assessments.”

Simon Gudgeon, a sculptor whose Sculpture by the Lakes park abuts the land that the council has earmarked for the three quarries, is also angry at what he sees as a lack of consultation.

“It is a misrepresentation to suggest that we have been consulted. We have not,” he said. “And in making its case, Dorset County Council states repeatedly that it is not necessary to go into great detail about the impact at this stage.

“There is a presumption towards development now and mitigation later, and that simply isn’t good enough. They can’t just dig up the countryside without carrying out all the necessary checks because they’re under pressure from the building industry and government.”

The situation in south Dorset is set to be mirrored at sites around the country, according to a spokesman for Straitgate Action Group, an organisation set up 15 years ago to fight a proposal for a 150-acre quarry near Ottery St Mary in east Devon.

“New homes equal new quarries and inevitably, the Prime Minister’s call for more houses to be built will mean that local authorities will be put under even greater pressure to agree quarry proposals,” he said.

There are about 1,300 quarries in the UK producing material valued at £3bn a year, according to the British Aggregates Association. Roughly half of these yield sand and gravel – used to make concrete and mortar – and the remainder provide the crushed rock that is used predominantly for road construction.

Aggregate accounts for more than half of construction materials by weight, and for every new home an average of 60 tons is required.

An alternative to digging new pits is investment in secondary aggregate – or recycled minerals.

“The Government needs to create jobs … by regenerating empty homes and derelict urban sites, instead of forever developing [new homes] in London and the Home Counties,” said Jonathan Essex, a Surrey county councillor and chair of the South East Green Party. “Furthermore, proper reuse and recycling of construction materials and demolition waste will drive down the amount of new quarried material we need.”

The Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) said: “We want to deliver the homes this country needs to ensure anyone who works hard and aspires to own their own home has the opportunity to do so. We are also encouraging new development on brownfield land and expect to see planning permissions for homes in place on 90 per cent of suitable brownfield sites by 2020.”

The department also states that in 2011, recycled and secondary sources accounted for 30 per cent of all aggregates used.

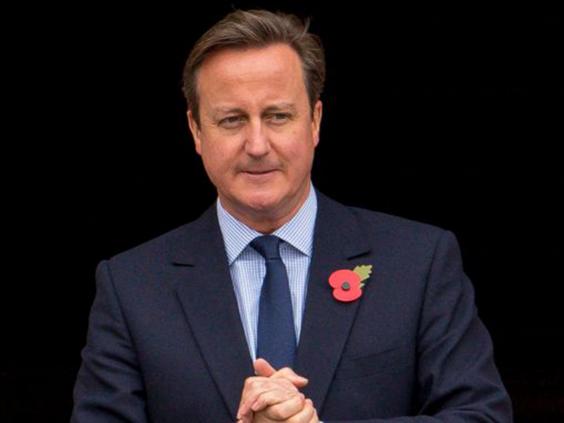

The NPPF, introduced in 2012, was meant to be the final word on reform of the planning system, but David Cameron’s call for a million new homes has signalled his determination to speed up the process.

Bob Brown, a minerals expert with the Campaign for the Protection of Rural England, said the NPPF claimed to be in favour of sustainable development. “Yet quarrying can hardly be described as ‘sustainable’ in a literal sense,” he said. “Hard rock and sand and gravel are finite resources which can only be quarried once. They should be extracted only in sufficient quantities to meet carefully assessed needs.”

Mr Gudgeon said the whole NPPF premise was flawed. “Who says a quarry is necessary? We are dictated to by the construction industry in whose interest it is that supply continues,” the sculptor said. “Sadly, many local authorities are failing in their duty to balance those economic demands with the impact on their taxpaying residents and the environment. More often than not they seem more motivated by complying with the NPPF and working with the quarrying companies.”

Ultimately, the job of safeguarding the countryside may fall to local residents like Clare Dobie, who led a campaign against a quarry at Coleman’s Farm in Essex.

In rural areas, Ms Dobie said, there were unlikely to be large numbers of people with expertise in quarrying to fight extraction proposals.

“Quarrying is in itself complex. It’s very technical,” she said. “The developer, on the other hand, has professionals on tap to deal with it all – and they have deep resources.”