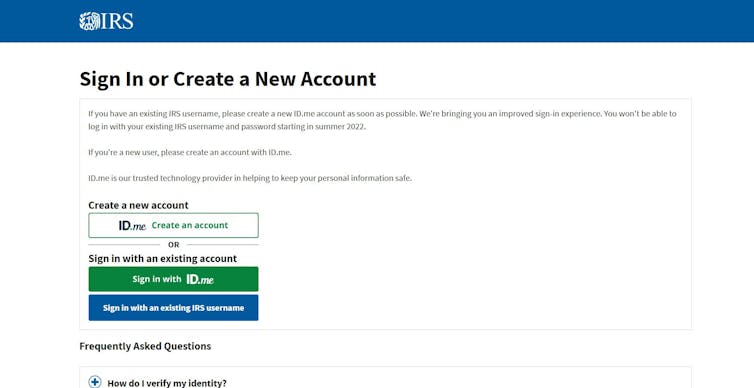

The U.S. Internal Revenue Service is planning to require citizens to create accounts with a private facial recognition company in order to file taxes online. The IRS is joining a growing number of federal and state agencies that have contracted with ID.me to authenticate the identities of people accessing services.

The IRS’s move is aimed at cutting down on identity theft, a crime that affects millions of Americans. The IRS, in particular, has reported a number of tax filings from people claiming to be others, and fraud in many of the programs that were administered as part of the American Relief Plan has been a major concern to the government.

The IRS decision has prompted a backlash, in part over concerns about requiring citizens to use facial recognition technology and in part over difficulties some people have had in using the system, particularly with some state agencies that provide unemployment benefits. The reaction has prompted the IRS to revisit its decision.

As a computer science researcher and the chair of the Global Technology Policy Council of the Association for Computing Machinery, I have been involved in exploring some of the issues with government use of facial recognition technology, both its use and its potential flaws. There have been a great number of concerns raised over the general use of this technology in policing and other government functions, often focused on whether the accuracy of these algorithms can have discriminatory affects. In the case of ID.me, there are other issues involved as well.

ID dot who?

ID.me is a private company that formed as TroopSwap, a site that offered retail discounts to members of the armed forces. As part of that effort, the company created an ID service so that military staff who qualified for discounts at various companies could prove they were, indeed, service members. In 2013, the company renamed itself ID.me and started to market its ID service more broadly. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs began using the technology in 2016, the company’s first government use.

To use ID.me, a user loads a mobile phone app and takes a selfie – a photo of their own face. ID.me then compares that image to various IDs that it obtains either through open records or through information that applicants provide through the app. If it finds a match, it creates an account and uses image recognition for ID. If it cannot perform a match, users can contact a “trusted referee” and have a video call to fix the problem.

A number of companies and states have been using ID.me for several years. News reports have documented problems people have had with ID.me failing to authenticate them, and with the company’s customer support in resolving those problems. Also, the system’s technology requirements could widen the digital divide, making it harder for many of the people who need government services the most to access them.

But much of the concern about the IRS and other federal agencies using ID.me revolves around its use of facial recognition technology and collection of biometric data.

Accuracy and bias

To start with, there are a number of general concerns about the accuracy of facial recognition technologies and whether there are discriminatory biases in their accuracy. These have led the Association for Computing Machinery, among other organizations, to call for a moratorium on government use of facial recognition technology.

A study of commercial and academic facial recognition algorithms by the National Institute of Standards and Technology found that U.S. facial-matching algorithms generally have higher false positive rates for Asian and Black faces than for white faces, although recent results have improved. ID.me claims that there is no racial bias in its face-matching verification process.

There are many other conditions that can also cause inaccuracy – physical changes caused by illness or an accident, hair loss due to chemotherapy, color change due to aging, gender conversions and others. How any company, including ID.me, handles such situations is unclear, and this is one issue that has raised concerns. Imagine having a disfiguring accident and not being able to log into your medical insurance company’s website because of damage to your face.

Data privacy

There are other issues that go beyond the question of just how well the algorithm works. As part of its process, ID.me collects a very large amount of personal information. It has a very long and difficult-to-read privacy policy, but essentially while ID.me doesn’t share most of the personal information, it does share various information about internet use and website visits with other partners. The nature of these exchanges is not immediately apparent.

So one question that arises is what level of information the company shares with the government, and whether the information can be used in tracking U.S. citizens between regulated boundaries that apply to government agencies. Privacy advocates on both the left and right have long opposed any form of a mandatory uniform government identification card. Does handing off the identification to a private company allow the government to essentially achieve this through subterfuge? It’s not difficult to imagine that some states – and maybe eventually the federal government – could insist on an identification from ID.me or one of its competitors to access government services, get medical coverage and even to vote.

As Joy Buolamwini, an MIT AI researcher and founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, argued, beyond accuracy and bias issues is the question of the right not to use biometric technology. “Government pressure on citizens to share their biometric data with the government affects all of us — no matter your race, gender, or political affiliations,” she wrote.

Too many unknowns for comfort

Another issue is who audits ID.me for the security of its applications? While no one is accusing ID.me of bad practices, security researchers are worried about how the company may protect the incredible level of personal information it will end up with. Imagine a security breach that released the IRS information for millions of taxpayers. In the fast-changing world of cybersecurity, with threats ranging from individual hacking to international criminal activities, experts would like assurance that a company provided with so much personal information is using state-of-the-art security and keeping it up to date.

Much of the questioning of the IRS decision comes because these are early days for government use of private companies to provide biometric security, and some of the details are still not fully explained. Even if you grant that the IRS use of the technology is appropriately limited, this is potentially the start of what could quickly snowball to many government agencies using commercial facial recognition companies to get around regulations that were put in place specifically to rein in government powers.

The U.S. stands at the edge of a slippery slope, and while that doesn’t mean facial recognition technology shouldn’t be used at all, I believe it does mean that the government should put a lot more care and due diligence into exploring the terrain ahead before taking those critical first steps.

James Hendler receives funding from IBM, DARPA, and the NSF. He is a Professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, affiliated with the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) and consults or has consulted for a number of government agencies. The opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the ACM or any of the other organizations with which he is affiliated.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.