Gothic architectural aspiration was unequivocally bound for the heavens. From about 1150, in order to support the weight of the increasingly vertiginous vaulted ceilings, reduce the thickness of walls and allow a glazed clerestorey (the upper part of the nave with a series of windows to provide light), flying buttresses were used. They bridged over the width of a side aisle to provide support for the main roof.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

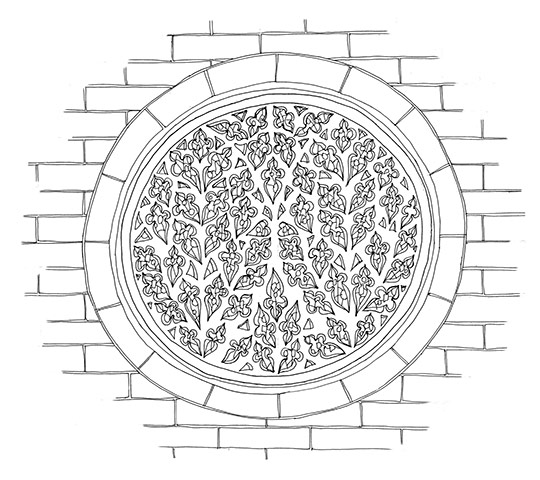

Tracery is the name for the stonework supporting the glass in a gothic window. During the 12th and early 13th centuries plate tracery was used, whereby geometric shapes were cut out of the wall. This evolved into bar tracery in about 1240, which became increasingly more decorative, with slender moulded mullions providing vertical support and shaped masonry creating decorative patterns in the upper parts. As the century progressed, designs became more complex.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

Circular windows were not a gothic invention, but the rose window – named because of its petal-like shape formed by its tracery – became a key feature of gothic churches. As gothic architecture developed, the form of the rose window became increasingly intricate and sophisticated, often encasing elaborate, stained-glass panels. Lincoln Cathedral’s Bishop’s Eye and the window in the north transept of Westminster Abbey are good examples.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

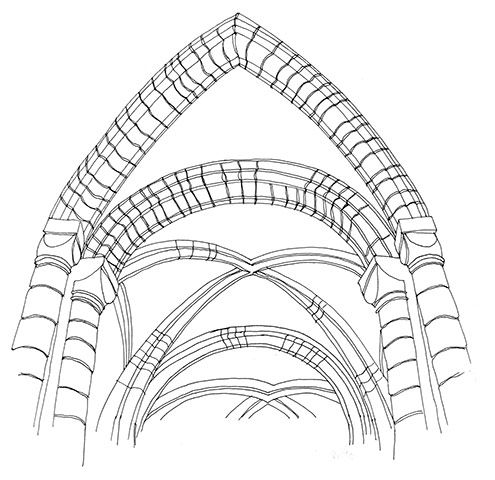

Like windows, the arches of vaulted roofs became pointed in the gothic period. A further structural innovation was the increased use of stone ribs within the vault, which provided support for the roof as well as decoration.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

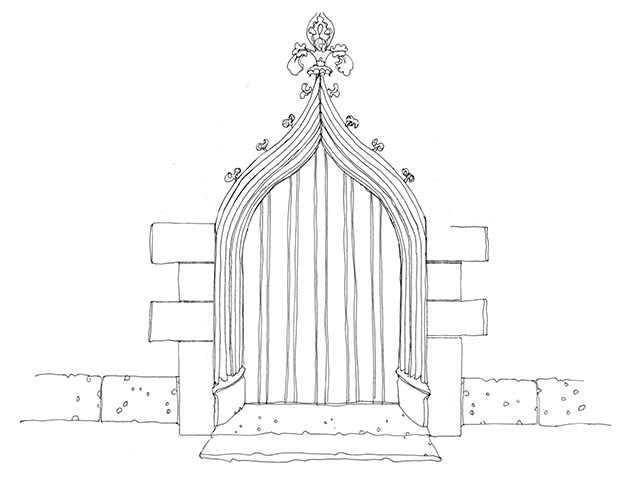

An arch that curves on both sides to reach a point at the top, the pointed (or ogival) arch is found wherever there is need for a vaulted shape, both structurally and decoratively. Though its roots are in Islamic architecture, the pointed arch came to be a crucially defining element of gothic architecture.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

As the mullions became ever thinner, perpendicular-style windows (c1380−1520) maximised the glazed areas – the mullions continued right up to the window arch in continuous vertical lines, creating a grid-like mesh of lines that might contain elaborate stained glass panels.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

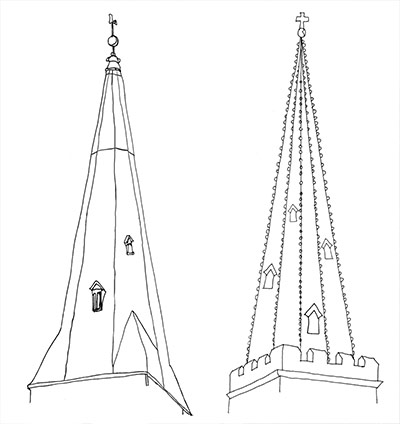

The early gothic broach spire (pictured above on the left) is a tapering octagonal spire with sloping triangular sections of masonry (broaches), by which its eight sides connect to a square base. From the 14th century, the decorated style sees broaches disappearing in favour of the parapet (right in the above illustration), which forms the base of the needle spire: a steeply pitched and extremely delicate shard, sometimes covered with lead, built to pierce both cloud and shine.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

The hammerbeam was another key player in the late gothic skyward thrust, allowing high-status timber roof structures to attain maximum, uninterrupted height between floor and apex. Short horizontal beams, supported by curved braces, rose inwards and upwards in steps, while leaving the internal space (often an open hall) free of overhead obstruction.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

A curve made of two arcs, flowing upwards from concave to convex like an S. Though the Romans knew about these beauties, ogee arches (formed by two ogees) were typical of the decorated gothic style, frequently found in openings, windows and other decorative elements.

Illustration: Emma Kelly