What does Gordon Lightfoot’s musical legacy mean for Canadians and for the history of Canadian music? In the wake of the singer-songwriter’s death on May 1, it has been hard to answer this question.

The media has been awash in tributes that celebrate Lightfoot’s music as somehow quintessentially Canadian. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Canada’s prime minister, responding to Lightfoot’s death, said he’d “captured our country’s spirit in music.”

But these tributes blur the reality that Lightfoot was a musician who had a much wider influence on the popular music scene of the 1970s, well beyond Canada’s borders.

A powerful nostalgia

Lightfoot’s voice is undeniably recognizable to many Canadians, and the cluster of songs that have enjoyed a long life on Canadian radio — and therefore in the Canadian consciousness — obviously engender a powerful nostalgia for an earlier time.

With his death, he seems to have been canonized in the same vein as Gord Downie, lead singer of the band The Tragically Hip. Downie died in 2017 and was immediately eulogized as “Canada’s unofficial poet laureate.”

Like Downie and The Hip, some of Lightfoot’s music is rooted in Canadiana. Perhaps no song embodies this more than “Railroad Trilogy,” in which Lightfoot romanticizes the building of the trans-national railroad and the history of colonial Canada.

But, also like Downie and The Hip, Lightfoot goes beyond this romantic narrative of Canada’s history with an invocation of the country’s deeper past: “Long before the white man and long before the wheel, when the green dark forest was too silent to be real.”

Nationalistic hot takes

Such nuanced meditations on the Canadian landscape and Canadian history have been largely lost in the effusive eulogies offered up by the media, politicians and Lightfoot’s musical peers. Blue Rodeo frontman Jim Cuddy said that Lightfoot matters so much because he allowed Canadians to “embrace our Canadian-ness.”

Trudeau claimed that Lightfoot “helped shape Canada’s soundscape,” and that he was “one of our greatest singer-songwriters.” Still other critics and commenters characterize Lightfoot as a storyteller, relating Canadian stories to a homegrown audience: “A Canadian who sang about Canadian things.”

These decidedly nationalistic takes on Lightfoot and his music are curious, given that he is a performer who peaked in the mid-1970s and whose music has long been out of style. How, then, did Lightfoot suddenly become Canada’s greatest musical treasure?

It’s not really so sudden, if we recognize that Lightfoot was a very popular singer-songwriter in his heyday in both Canada and the United States. He enjoyed middling success with his earliest albums in the 1960s, but then broke out with several key albums on Reprise Records in the following decade.

Chart singles

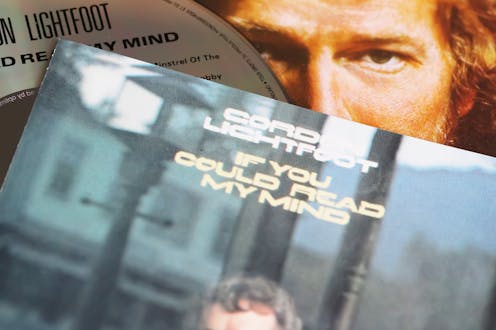

A series of well-known singles were chart-topping hits in Canada and the U.S.: “If You Could Read my Mind” (1970), “Carefree Highway,” “Sundown” (1974), “Rainy Day People” (1975) and “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” (1976). These helped to established Lightfoot as an international name in the world of folk and country music.

Other popular American artists of the time, including Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, Barbra Streisand and even Elvis Presley, recorded Lightfoot’s songs, firmly establishing Lightfoot’s reputation as an important singer-songwriter.

As Dylan once famously observed, he could not think of a single song by Lightfoot that he didn’t like. Later in his career, Lightfoot was honoured by the American Songwriter’s Hall of Fame, was a recipient of the Order of Canada and was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame by Dylan himself.

Types of nostalgia

But what about this issue of Lightfoot as a musician who somehow captured Canada’s spirit in his songs? This is a contentious and ambiguous claim. I would argue that contrasting types of nostalgia are at the root of this evaluation of Lightfoot and his oeuvre.

The Russian philosopher and cultural theorist Svetlana Boym famously identified two distinct — but not necessarily mutually exclusive — types of nostalgia: restorative and reflective.

Restorative nostalgia underwrites the kind of nationalistic longing that has characterized the celebration of Lightfoot’s musical legacy — that he is “typically Canadian,” as fellow Canadian singer-songwriter Murray McLauchlan insists.

Reflective nostalgia, by contrast, does not revel in the past nor attempt to recover it. Rather, as Boym observes, it expresses uncertainty about the past as it “dwells on the ambivalences of human longing and belonging.”

Indeed, in surveying the mainstream eulogies of Lightfoot, the tensions and contradictions between these two types of nostalgia are immediately evident: McLauchlan lauds Lightfoot as typically Canadian in the same article that insists the deeply personal and emotive nature of Lightfoot’s music and message make it “universal.”

A reflective nostalgia

The very fact of Lightfoot’s popularity in the 1970s, and the attractiveness of his songs to legendary American musicians like Cash, Dylan and Presley, also belies the notion of Lightfoot’s songs as quintessentially Canadian.

At their best, Lightfoot’s songs — ranging from folksy, rambling tunes about riding the rails to tender ballads recounting love and loss to epic narratives about ships and sailors lost in storms — invoke a reflective nostalgia.

His fluid, gentle vocal delivery and simple, direct sentiments lean strongly towards “human longing and belonging,” much more so than they paint a compelling or accurate portrait of Canada.

Simply casting Lightfoot as an exemplar of Canadian-ness overshadows Lightfoot’s legacy. He was a songsmith and a musician who toiled for his entire career — spanning nearly six decades — to bring words and music together in meaningful and enduring ways.

Alexander Carpenter does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.