Google’s parent company Alphabet has lost a hefty US$100 billion (£83 billion) or nearly a tenth of its market value after its new AI chatbot, Bard, botched an answer to a query on an ad promoting its launch. It claimed that the James Webb space telescope took the first pictures of planets outside the Earth’s solar system when in fact it was the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope.

At the same time, Microsoft saw its shares rise 3% on announcing that it would be integrating ChatGPT into Bing, Office and Teams. Microsoft is a significant shareholder in OpenAI, maker of this much-heralded AI chatbot.

Many are asking if we are witnessing Google’s Kodak moment, in reference to the American camera giant’s famous demise at the hands of digital photography. That could be overstating it, but we certainly think there is some merit to investors’ concerns for Google’s future as a search engine company.

How disruption happens

Bard making a mistake is not a problem in itself. ChatGPT is known to give wrong answers to queries with unsettling confidence. The big market reaction against Alphabet was more because the launch debacle broke the proverbial camel’s back. If Google can’t even run a convincing launch ad about its new technology, went the thinking, can it really defend its search business?

In our experience, firms don’t usually get disrupted because they lack the technology or the resources. More commonly it’s either because they lack imagination or struggle to re-invent themselves – often out of fear that developing a new business will harm an existing one (known as cannibalisation).

Lack of imagination is mostly the problem with longstanding incumbents. Kodak, for example, couldn’t imagine a world without photographic film and hard prints and paid a heavy price. Equally, hotel groups were completely caught on the hop by Airbnb. They had little response except to lobby government authorities en masse against the service.

On the other hand, Google has been at the forefront of developing the technology behind AIs like ChatGPT. Known as large language models or LLMs, they essentially work by assembling arrays of very powerful computers and “training” them on huge quantities of information from the internet and elsewhere.

Google’s research scientists wrote the breakthrough paper in 2017 in this area called “Attention is all you need”. Google incorporated LLMs into the likes of Google Translate to much success, though never into its mainstream search business. It seems likely that it fears cannibalisation and the difficulty of reinventing its search business. Unfortunately, the status quo doesn’t look viable either.

Google utterly dominates search, with 84% of global traffic, garnering 70% of its revenues from this and related markets. Having created a business on such a scale, it effectively has a monopoly (outside certain countries like China that do things their own way).

The problem is that AI chatbots like ChatGPT circumvent the need for a search engine by giving precise and, in most cases, correct and creative answers to complex human queries. ChatGPT has become the fastest adopted consumer app of all time, with more than 100 million users since November. And besides Bard, various other companies, including Chinese search giant Baidu, are well advanced in developing LLMs of their own. If there’s a better way to find out what’s on the internet, why bother Googling anything anymore?

Making money from AI chatbots

For now, the business model for AI chatbots is unclear. Search is free for end users thanks to advertisers paying on the other end for customer traffic they receive from valuable search terms. It is a predictable high-margin business.

AI chatbots on the other hand are tricky. Would ads need to be inserted in responses to convince users to click on certain advertiser websites? Would that appear to be inauthentic and cause fallout? How many ads would be too many?

There’s no telling to what extent this would cannibalise Google’s search business, which must make it terrifying for the management. Again, consider Kodak. It bought photo-sharing platform Ofoto in 2001 and could have developed it into a social media platform. Instead, it tried to protect its business by encouraging users to print more pictures rather than sharing them with others.

This is how successful companies’ core capabilities end up becoming their core rigidities. Microsoft doesn’t have this problem precisely because it has never managed to compete with Google successfully since launching Bing in 2009. It only earns about 6% of its revenues from search, so has far less to lose from disruption in the sector. It has already been giving investors a sense of how it will incorporate ChatGPT into Bing’s ad model.

The incumbent problem

Google’s innovation has already been atrophying in recent years. It has shut down promising businesses, such as gaming platform Stadia and automated reservations tool Duplex on the Web. Elsewhere it has been late, playing catch-up to Amazon’s Echo smart speakers with Google Home.

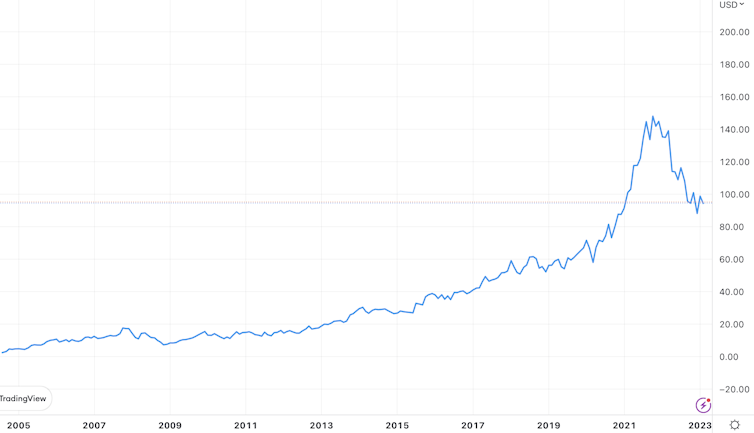

Management missteps are partly to blame, but so are impatient requirements on making a return. The stock market has rewarded Google’s laser-sharp focus on revenue growth and profitability, incentivising the management to be less patient with their investments. Kodak’s market valuation was the highest in its history in 1996 before the global shift to the internet ushered in a remarkable collapse. Perhaps we will say the same about Alphabet/Google in 2021.

Alphabet/Google share price

In our experience, companies would much rather have competitors kill their golden goose than do it themselves. This is the trap Google must avoid. The only option is to start cannibalising its search business.

Google could copy Microsoft’s approach with Bing and introduce Bard results as just one of the responses to search queries. This might lower its ad sales as there is no real bidding for a bot’s answer and no clicks that can take searchers to monetisable partner sites. But launch this in beta, making it only accessible to those who pre-register, and you at least contain the impact. Learn from the experience, test different monetisation models and scale only when you see what works best.

Above all, Google cannot continue to thrive or even survive by thinking like an incumbent. It needs to re-invent itself. This means leaving something on the table, not trying to carry everything it possesses into the future. The sooner it realises this, the higher the likelihood it will survive.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.