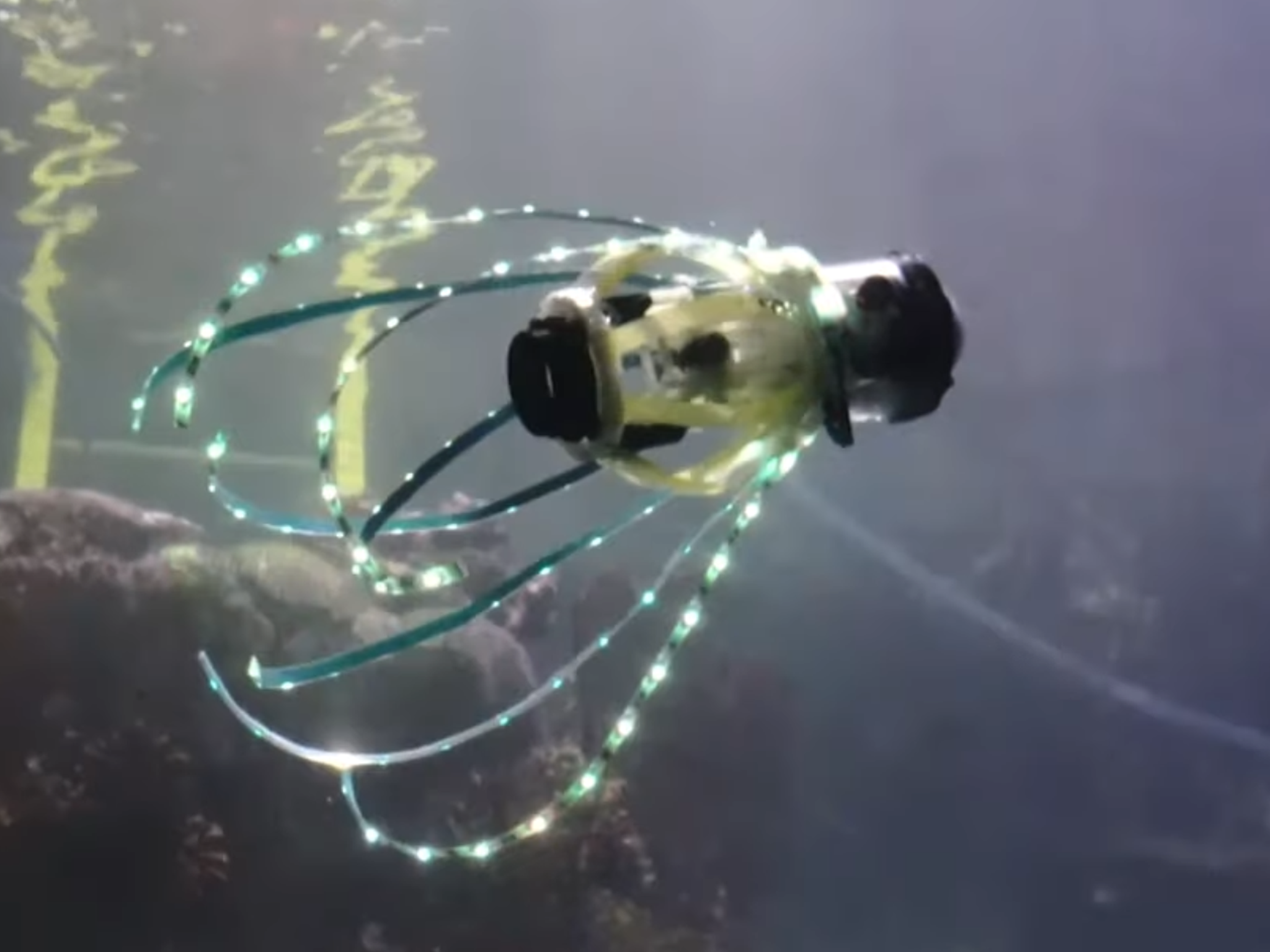

A new squid-like robot has can swim on its own and take pictures.

The machine was built to explore the sea by researchers at the University of California San Diego.

The robot propels itself by shooting jets of water behind it; it takes in a large amount of water into its body, and then compresses itself to blast it out behind it.

The machine’s body is made of acrylic polymer, supported by 3D-printed and laser-cut parts; its soft body means that it will not injure fish or coral, and can also maneuver more easily than larger, more rigid robots.

The ‘ribs’ of the squid are connected to two circular plates, with one attached to a nozzle for shooting water and the other carrying a waterproof camera or other sensor.

The researchers decided that a cephalopod – the group of marine animals that includes squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus – was the best choice of design because of their speed.

Squid can reach the fastest speed of any aquatic invertebrates, through a similar natural jet propulsion system.

The robot can reach a speed of approximately 18 to 32 centimeters per second, which equates to roughly half a mile per hour - faster than most other soft robots, they claim.

Real squid, by contrast, can travel at between 23 and 25 miles per hour.

The robot also has its own power source so it can operate for a period of time without needing to be connected to other equipment.

"Essentially, we recreated all the key features that squids use for high-speed swimming," said Michael T. Tolley, a professor in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at the university.

"This is the first untethered robot that can generate jet pulses for rapid locomotion like the squid and can achieve these jet pulses by changing its body shape, which improves swimming efficiency."

The researchers first designed the robot to swim in a tank, before testing it in a larger aquarium.

“After we were able to optimize the design of the robot so that it would swim in a tank in the lab, it was especially exciting to see that the robot was able to successfully swim in a large aquarium among coral and fish, demonstrating its feasibility for real-world applications,” said Caleb Christianson, who led the study.

The researchers published their work in a recent issue of Bioinspiration and Biomimetics.