“Going home” is a classic metaphor for exiting prison. But most people exiting prison in Australia either expect to be homeless, or don’t know where they will be staying when released.

Our recent research for AHURI (the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute) shows post-release housing assistance is a potentially powerful lever in arresting the imprisonment–homelessness cycle.

We found ex-prisoners who get public housing have significantly better criminal justice outcomes than those who receive private rental assistance only.

The benefit, in dollars terms, of public housing outweighs the cost.

Read more: How we can put a stop to the revolving door between homelessness and imprisonment

The imprisonment-homelessness connection

There is strong evidence linking imprisonment and homelessness. Post-release homelessness and unstable housing is a predictor of reincarceration. And prior imprisonment is a known predictor of homelessness. It is a vicious cycle.

People in prison often contend with:

- mental health conditions (40%)

- cognitive disability (33%)

- problematic alcohol or other drug use (up to 66%) and

- past homelessness (33%).

People with such complex support needs are often deemed “too difficult” for community-based support services and so end up entangled in the criminal justice system.

Also, prisons are themselves places of stress and suffering. So people leaving prison a high-needs group for housing assistance and support.

There are about 43,000 people in prison in Australia. Over the year there will be even more prison releases (because some people exit and enter multiple times).

According to the latest published data:

- only 46% of releasees expect to go to their own home (owned or rented) on release

- more expect to be in short-term or emergency accommodation (44%) or sleeping rough (2%), or

- they don’t know where they will stay.

Ex-prisoners are the fastest growing client group for Australia’s Specialist Homelessness Services.

Over the past decade, imprisonment rates in Australia have been rising.

Meanwhile, funding for social housing – public housing provided by state governments, and the community housing provided by non-profit community organisations – has been declining in real terms.

We must turn both those trends around.

The difference public housing makes

In our research, we investigated the effect of public housing on post-release pathways. We analysed data about a sample of people with complex support needs who had been in prison in NSW.

The de-identified data show peoples’ contacts before and after prison with various NSW government agencies, including criminal justice institutions and DCJ Housing, the state public housing provider.

We compared 623 people who received a public housing tenancy at some point after prison with a similar number of people who were eligible for public housing but received private rental assistance only (such as bond money).

On a range of measures, the public housing group had better criminal justice outcomes.

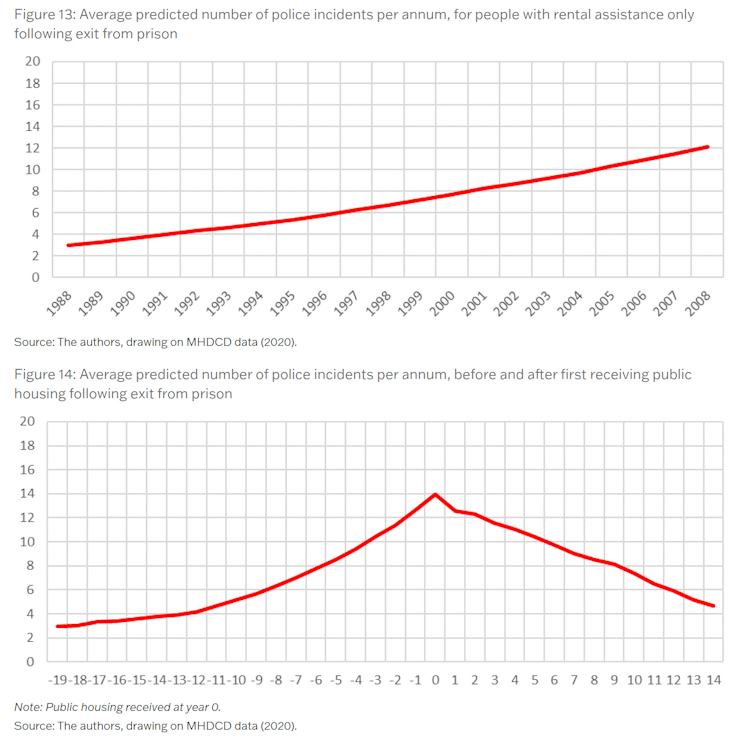

The charts below compare the number of police incidents for each group.

The first chart shows recorded police incidents for the private rental assistance group, which gradually rose over the period for which we have data.

The second chart shows police incidents for the public housing group: they also had a rising trend, until they received public housing (year 0 on the x-axis), after which police incidents went down 8.9% per year.

For the housed group:

- court appearances were down 7.6% per year

- proven offences (being found guilty of something at trial) were down 7.6% per year

- time in custody was down 11.2% per year

- time on supervised orders (court orders served in the community, including parole) initially increased, then went down 7.8% per year

- justice costs per person, following an initial decrease of A$4,996, went down a further $2,040 per year per person.

When we put a dollar value on these benefits, providing a public housing tenancy is less costly than paying Rent Assistance in private rental (net benefit $5,000) or assisting through Specialist Homelessness Services (net benefit $35,000).

Unfortunately, public housing is in very short supply.

For our public housing group, the average time between release and public housing was five years. Others are never housed.

Post-release pathways are fraught

We interviewed corrections officers, reintegration support workers, housing workers, and people who had been in prison, across three states.

They were unanimous: there is a dearth of housing options for people exiting prison.

A Tasmanian ex-prisoner, who lived in a roof-top tent on his car on release, said:

You basically get kicked out the door and kicked in the guts and they say, ‘Go do whatever you need to do, see ya’.

Planning for release is often last-minute. A NSW reintegration support worker told us:

It’s not coordinated. We’ll get a prison ringing up on the day of release saying, ‘Can you pick this woman up?’ on the day of release, when they knew it was coming months in advance. There’s no planning.

A housing worker in Victoria described those next steps as a series of unstable, short-term arrangements, beset by pitfalls:

They could easily be waiting a couple of years, realistically. And for them that’s a long time, and so far off in the distance it’s difficult to conceive of. And a long time in which for things could go wrong in their lives – to be homeless or back in prison, all sorts of things … What they do in the meantime: they couch surf, stay with family, stay in motels, stay in cars/stolen cars, stay with friends, sleep rough, all those things.

A Tasmanian corrections officer told us:

People want to come back to custody because they’ve then got a roof over their head. They don’t have to worry; they’re getting fed, they can stay warm.

It’s not just about housing support

Community sector organisations specialising in supporting people in contact with the criminal justice system, such as the Community Restorative Centre (CRC) in NSW, do extraordinary work providing services and support that aim to break entrenched cycles of disadvantage and imprisonment.

However, this sector’s funding has been turbulent, marked by short-term programs.

In another project by some members of this research team, we saw the difference CRC made to 275 of its clients over a number of years. This evaluation found supported clients had 63% fewer custody episodes than a comparison group – a net cost saving to government of $10-16 million.

These support services would be even more effective if clients had more stable housing. As it is, specialist alcohol and other drug case workers are often spending their time dealing with clients’ housing crises.

Secure, affordable public housing is an anchor for people exiting prison as they work to build lives outside of the criminal justice system.

It is also a stable base from which to receive and engage with support services. It pays to invest in both.

Read more: Caring for ex-prisoners under the NDIS would save money and lives

Chris Martin receives funding from the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) and the ACOSS-UNSW Poverty and Inequality Partnership. This story is part of The Conversation's Breaking the Cycle series, which is about escaping cycles of disadvantage. It is supported by a philanthropic grant from the Paul Ramsay Foundation.

Eileen Baldry receives funding from the ARC, the NHMRC and AHURI. She is affiliated with the Justice Reform Initiative, the NSW Ageing and Disability Commission, the Noffs Foundation and the Public Interest Advocacy Centre.

Patrick Burton is funded by the AHURI and is affiliated with the Justice Reform Initiative, Brain Injury Association of Tasmania and JusTas.

Rebecca Reeve receives funding from the Paul Ramsay Foundation. She is affiliated with the Social Outcomes Lab.

Rob White receives funding from the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute and is affiliated with the Justice Reform Initiative, Just Desserts (drug court support group) and the Brain Injury Association of Tasmania (criminal justice steering group).

Ruth McCausland receives funding from the Paul Ramsay Foundation, NHMRC, AHURI and Australian Partnership Prevention Centre, and is affiliated with the Community Restorative Centre.

Stuart Thomas receives funding from the ARC, Department of Health, National Mental Health Commission, Mental Health Victoria, Mind Australia, AHURI and ACEM. He is affiliated with the Law Enforcement and Mental Health Special Interest Group of the Global Law Enforcement and Public Health Association. .

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.