What is the meaning of last month’s resounding defeat of the Voice referendum? According to the Australian’s Paul Kelly, it “exposes Australia as two different societies — a confident, educated, city-based middle class and a pessimistic, urban and rural battler constituency” that is “hostile” to “change.”

This split, he believes, is “a threat to a cohesive and successful Australia as it tries to adapt to the globalised economy.”

Wait, apologies, I jumbled my notes. That was Kelly after the 1999 vote on the republic, a cause he was very much in favour of.

This time round his columns have run passionately against the proposed Voice, and his tea-leaf reading of very similar voting patterns — the Yes vote fading the further from CBDs — sits on a much more ideological plane.

Once again the big No vote points to a “divided nation,” but now the goodies and baddies are very clear. That “confident, educated, city-based middle class” cohort has become something malignant, purveyors of “progressive sophistry” and “progressive values” and “experiments… tampering with the once accepted but now eroding universal norms that defined the Australian nation.”

The fourteenth of October, to underline the point, was a “repudiation of elite morality and assumed moral superiority.” On and on Kelly goes, for more than 2300 words; quoting various “experts” to categorise this as our Trump/Brexit moment, the revenge of everyday, ordinary citizens tired of being scolded and looked down on.

The Professor has been castigating “elites” (with all the unacknowledged irony this encompasses from a person of his means and position) since at least the late Howard years, but whereas the group once largely consisted of inner-urban Labor and Greens supporters working in academia and the arts, big business — with its public pronouncements in favour of marriage equality and tackling climate change — seems also to now stand in Paul’s naughty corner. “Elite(s)” appears no less than seventeen times in last month’s tirade, along with thirteen mentions of “progressive(s).”

That pattern of higher support in the inner city ebbing lower as you approach the bush can actually be observed in every referendum this side of Robert Menzies’s attempt to ban communism in 1951. It was more pronounced in the 1999 vote (both for the republic and for a new constitutional preamble) and more pronounced again in 2023.

A Labor–Coalition city–rural split has also been growing at general elections, reaching its apogee in May last year. There is change afoot in the electoral arena, and it is also seen dramatically in the ever-plummeting support for major parties.

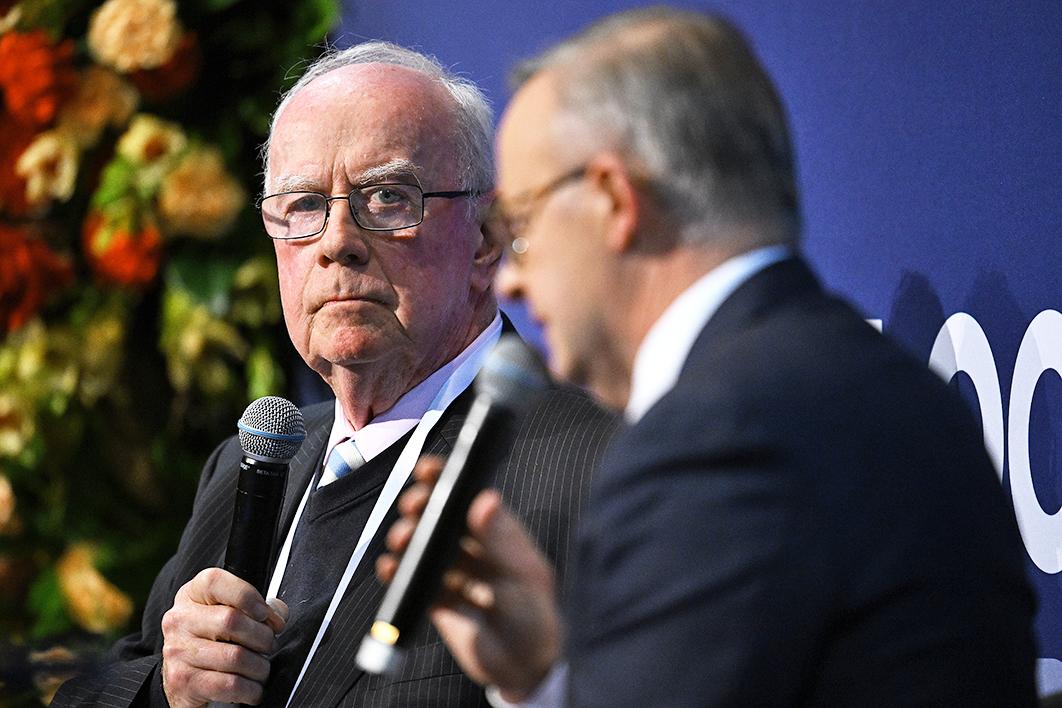

Kelly’s bitter deep dive is worth citing because it conveniently contains most elements of the gloating-dressed-as-analysis that has emerged from the No-supporting commentariat. Even more than most political journalists, he seems to be a hostage to the present, inhaling the current zeitgeist and reciting it with deep meaning and drama — and often at great length.

So what does the 40–60 Voice outcome tell us about the country? That Australia is racist? Or colour-blind? Or doesn’t like elites?

I don’t think this result should change or even reinforce anyone’s opinion about the nature of this country. Instead it verifies that Australians can be relied on to bury Labor government midterm referendums, regardless of the topic. Set your watch by it: early opinion polling shows overwhelming support; Liberal leader eventually opposes (because to do otherwise would be professionally fatal); the government, encouraged by the polling, still presses ahead. Then it all becomes an orgy of scarifying tales about the danger of messing with the Constitution — the blueprint of this country, the envy of the world. Former judges are exhumed to warn of the risk. Why are the government and its mates so desperate to do this? They’re spending how many millions on it? Such self-indulgence, such arrogance, who can resist reminding them who’s boss?

With counting over, the Voice slots in fourth out of Labor’s eleven midterm attempts to change the Constitution since federation. That’s not particularly bad.

What does set this vote apart is its makeup. Last century, decent statistical correlations could be observed between Labor two-party-preferred support at the previous election and Yes votes. Traditional high-income Liberal electorates reliably took their party’s cue and joined outer-suburban and regional Coalition supporters to deliver, overwhelmingly, above-average Nos.

This time around, that high-income territory is mostly in teal hands (but the locals still vote Liberal over Labor in two-party-preferred terms), and those electorates voted a higher-than-average Yes. It was much like the republic vote, when they could still be loyal Liberals by siding with treasurer Peter Costello rather than prime minister John Howard.

This change in behaviour in the former Liberal heartland was a major driver — perhaps the major driver — of the record city–bush divide.

That might have been because, as Kelly writes, the Voice was seen as a “moral” issue. How might a referendum on something mundane, like recognising local government, have gone? As a Labor midtermer it would have been thrashed, but would it have exhibited those heightened geographic differences or settled back to something more predictably partisan?

Kelly was just as strongly against marriage equality, and that 2017 survey also exhibited the city-to-bush pattern (overlaid by outsized No votes in some suburban electorates with high numbers of people from non-English-speaking backgrounds), but the overall outcome, a big win for Yes, precluded triumphalism. On that occasion, the elites were apparently vindicated.

There is one other tendency in the recent analysis, and not just on the No side. Some people see the referendum as an electoral test failed by the Albanese government. It was so out of touch on this issue, can it recover?

The vote has certainly brought Anthony Albanese, who evidently believed his special skill set would bring this home, thuddingly down to earth. It’s damaged him in the eyes of the political class — they will no longer marvel at his prowess — but does that matter in the long run? Probably not; he had to get real sometime. It was something people were forced to vote on, a tenth-order issue for the overwhelming majority, and won’t feature at all in the next campaign. There’s nothing in the historical record to suggest referendum losses portend the same at subsequent elections.

Kelly was at it again last week, presenting a strategy for Peter Dutton’s path to the Lodge — courtesy of the Voice vote. Acknowledging that it “is easy to exaggerate the meaning of the referendum,” he proceeded to do just that, finding in it a “strategic pathway” for the opposition and piling on advice for the Liberal leader’s “approach post-Voice.”

The old pro-business warrior now sounds decidedly blue Labo(u)r (or should that be “populist”?): companies get a serve for “defending their economic bottom line while doubling down on their promotion of social and environmental values.”

That tedious old chestnut, Menzies’s “forgotten people,” gets an awfully long workout in the context of an imaginary two-term strategy for Dutton, à la (without mentioning him by name) Tony Abbott. Back on terra firma, Dutton will be lucky to survive for just one term as opposition leader, let alone two. •

The post Getting the referendum wrong appeared first on Inside Story.