Let’s dial back to 1984 to begin the story of one of pop’s most tortuous births.

Frankie Goes To Hollywood, the unlikely first signing to producer Trevor Horn’s new ZTT label, have just scored huge hits with their debut single Relax and follow up Two Tribes. And basking in the glory of success, Horn and his team - ensconced in their own studio, with studio time being billed to the band, being taken from their royalties - would fret for weeks, months even, over the minutiae of every sound. After all, if the result was a hit, everyone’s a winner.

Basking in the glory of success, Horn and his team would fret for weeks, months even, over the minutiae of every sound

However, as the dust settled on Two Tribes and Horn encouraged the Frankies to start thinking about a follow-up (and an entire debut double album to follow) it soon became apparent that the band’s cupboard was bare.

In fact, Stephen Lipson, when speaking to the excellent 80sography podcast, confirmed that the band only appear on four of the 16 tracks on their Welcome To The Pleasure Dome debut. Difficult second album? How about a difficult third single…

Step up Bruce Wooley (one of the co-writers of Video Killed The Radio Star, a smash for Producer Trevor Horn’s Buggles and the co-writer of Horn’s smash hits for Dollar) and Simon Darlow (the keyboard player Horn turned to following Geoff Downes’ Buggles departure) who had been working on a track that might just save the day.

Horn liked the demo of Slave To The Rhythm and it was soon in the running as the next Frankie single. However, in mid ‘84, Slave was a very different beast to the track we know today.

Clocking in at 137bpm it was a stern, stomping, rocky thrash, and despite Horn and vocalist Holly Johnson’s best efforts to capture its magic, the demo did not go well.

ZTT was a subsidiary of Island Records and - eager to hear the next Frankie smash in progress - label Boss Chris Blackwell only confirmed Horn’s worst fears. Slave had to go back to the drawing board. But at least Blackwell “liked the title”, according to Horn, and - more usefully - made two suggestions that might just save the track.

The New York sessions did not go well...

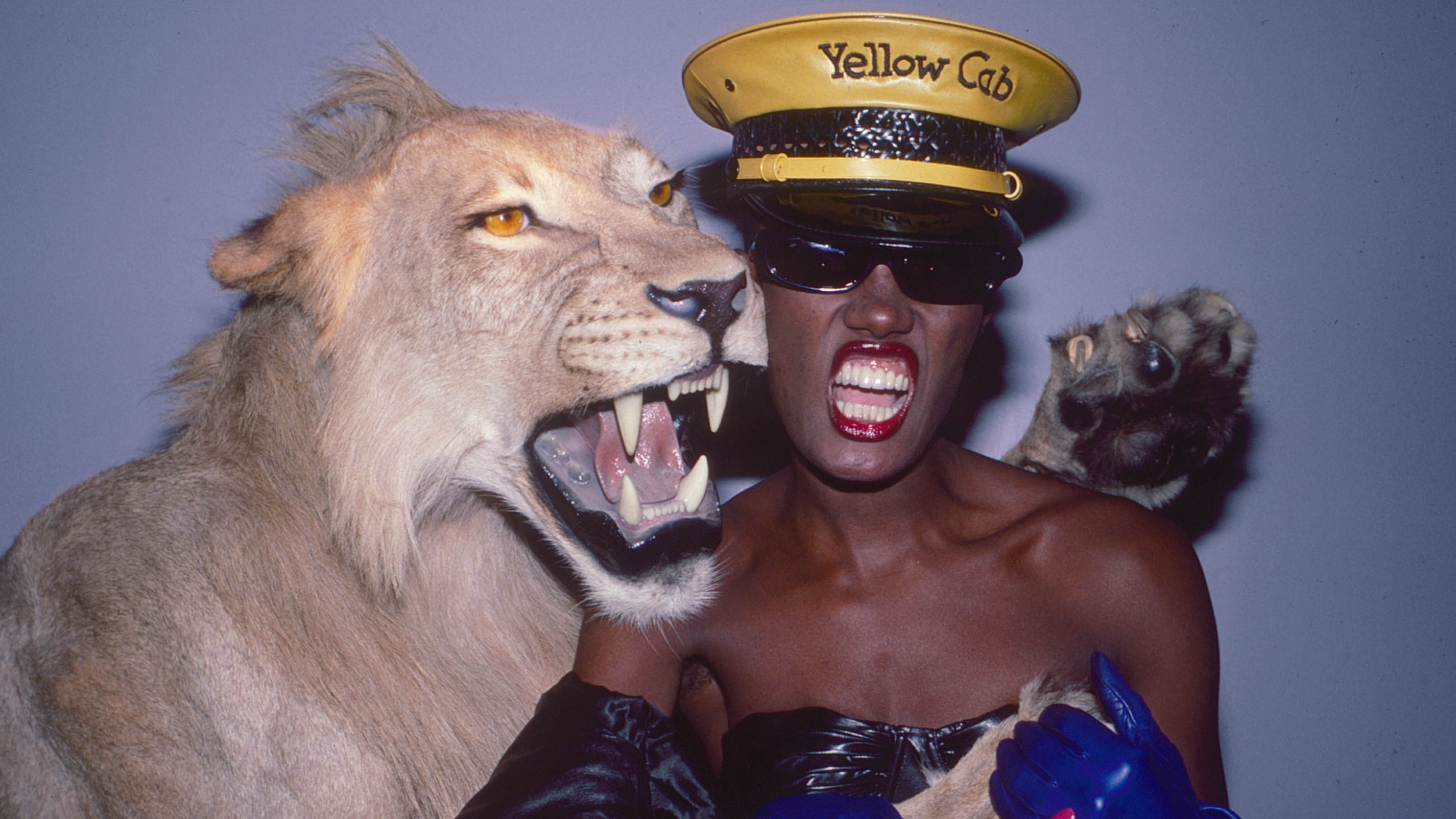

Blackwell’s first suggestion was that they re-record it to a ‘go-go rhythm’ (go-go being a genre that was very much in its short-lived ascendancy in 1984, most famously played out by the insanely funky Trouble Funk). And secondly that Horn scrap the Frankie demo and give the track to Island Records’ chanteuse in residence Grace Jones instead. Thus, Slave was lurched in the first of many new directions.

Opinions at this point differ as to how much Horn knew of go-go. Horn, speaking on the Rockonteurs podcast, states that the go-go switch was his idea and that he asked Blackwell to make the arrangement for a New York trip to secure top musicians’ services.

Right-hand man Lipson, however, insists that the team turned up at the Hit Factory sessions with literally no idea as to what go-go was and what they were going to record.

And the New York sessions did not go well. While the new drums and percussion they had on tap sounded great - Lipson claims that all he did was push up the faders and hit record to capture Slave’s famous rhythm track - the 97bpm groove the band were churning out simply didn’t fit with the hard-stepping 137bpm track they were there to complete.

Worse, the band proved undirectable, being completely unable to follow a song structure or deviate in any way from that same, simple go-go loop. “You set them going… And that was it.” Horn complained.

Most pressing, however, was the fact that, despite Blackwell’s insistence, the song provided by Wooley and Darlow just wasn’t go-go. What could be done?

The team had the band and The Hit Factory booked for two days, and - due to union rules - were forced with a hard 5pm stop on both days, precluding the meandering creative all-nighters they were used to.

Letting the band go a day early, Horn, Lipson and keyboard player (to become producer) Andy Richards decamped to their hotel with a bass, guitar, Roland JX-8P synth and Roland TR-808 drum machine borrowed from the studio to set about reworking the song overnight to fit the funky 97bpm they’d just captured.

Musically, the chords just weren’t working out, but Lipson suggested to Richards that he flip their order for the verses, giving a steady rise, rather than a rocky descent. Inspired by the breakthrough and playing with the presets on the loaned JX-8P, Richards soon found a sound to his liking.

The famous chords of Slave To Rhythm’s intro and chorus are actually fairly simple, but sound anything but. The trick is the layering of two of the JX-8P’s presets. The first, Soundtrack (preset 16) is a mournful synth pad, and the second is the sound literally next to it (preset 17) Fat Fifths, a synth brass sound with one oscillator tuned up a fifth (seven semitones) producing a fatter, jazzier sound.

Thus, playing what are in effect simple, three-note chords produces a super complex six-note output. It’s that Fat Fifths preset that delivers all the polychord magic. Some chords given the treatment sound atonal and unpleasant, but some chords - such as those in the intro to Slave - sound fantastic.

The sound proved so enduring that Richards couldn’t resist giving it another airing, using it to provide the intro to Fuzzbox’s Versatile For Discos And Parties, which he produced four years later. And Roland took the hint too, providing reworked versions of the warm Soundtrack preset through its subsequent D-50, D-70 and MT-32 synths (and multiple spin-offs) though this time incorporating an oscillator offset by a fifth, enabling users to get the Slave sound without having to layer it up.

A more leisurely, less chanted, more melodic vocal melody arose on top of the new chords (with additional lyrics by Horn to fill the gaps) and in a night the problem was solved. Technically, the New York trip had produced nothing more than eight bars of sampled go-go percussion, but in reality the trio headed back to London with the workings of what could be a hit.

But the 137bpm ‘fast version’ wasn’t dead just yet. With weeks of work invested in the track already - not least the Frankie demo - Horn encouraged Lipson to keep experimenting. Multiple takes and multiple ideas simultaneously took shape on Sarm Studios’ Synclavier digital workstation, and when the Synclavier was upgraded with polyphony that only meant that - of course - even more options were available to Lipson and thus the creative ‘what if…’ process began all over again…

Something had to give, and soon the team arrived at a potentially calamitous impasse - having an orchestra booked for two days and not being sure what they wanted them to play…

To save face, it was quickly decided that they would focus on ‘the fast version’ but would record the orchestra for the ‘slow version’, too, “just in case”. Thus, multiple passes were recorded of ‘the fast version’, with a single perfunctory take of ‘the slow version’ also being committed to digital tape.

Likewise, when Jones herself was summoned for lead vocals, she too had to record two versions of the song. It’s interesting to note that while the whole Slave To The Rhythm project would eventually take over a year to complete, Lipson estimates that they had the services of Grace Jones herself for “about ten hours”.

Asked in a Guardian webchat how Jones was to work with, Horn insisted, "Grace was great. Working with her's always good.

"Getting her to the studio was tough! But once we got her there, she was wonderful. Slave to the Rhythm, we really sprung it on her."

Graciously performing both the Wooley/Darlow and the Wooley/Darlow/Horn/Lipson versions of the song, Jones of course put her own stamp on the track. Her performance is full of spontaneous ad-libs, from the opening, absentmindedly muttered “I’m just playing around”, through to the “Oh, baby…” to the track’s non-scripted spectacular conclusion…

Upon hearing the freshly recorded, swirling orchestral build and dramatic drop from 3:55, Jones thought it sounded like an old ‘Saturday Night Live’-style chat show theme. Thus, when the vital moment came around during her vocal, a mickey-taking Jones was sufficiently caught up in the action to announce “And now… Ladies and gentlemen… Heeeeere’s Grace!”

Thus magic was captured. Twice. And with the first anniversary of Wooley and Darlow’s demo approaching, the team naggingly began to approximate the expenses run up so far in producing - to that moment - precisely nothing.

Slave had turned into a foolish folly and the situation couldn’t be ignored further. What was worse, Jones was by then out of contract with Island and so they had no means of extracting further work from her for an album.

There was only one thing for it. To spin the many tries, retries, takes, alternative mixes and Slavish experiments into the album that she could no longer complete. An eight-track album… Of one song.

It was a brave move even for the wild times of 1985, but it was a gamble that paid off. Never before or since has one piece of music been sliced, diced, reheated and re-served into as many different delicacies and, despite sounding preposterous on paper, Slave To The Rhythm - the album - remarkably stacks up.

Interestingly the version that was finally selected as the single appears as Ladies And Gentlemen: Miss Grace Jones, the last track on the album, while the track actually entitled Slave To The Rhythm is a radically alternative version which still crops up on compilations and playlists in error to this day.

It’s the opening track - Jones The Rhythm - that’s the closest to the original ‘fast’, Wooley and Darlow version that, while excellent, shows that the trip to New York and Horn and Lipson’s rewrites were worth the wait. (It’s worth saying at this point that there’s another ‘fast version’ of the song - one that sounds like a simple Synclavier demo - which appears on the B-side of the physical single, and is yet to appear in digital form).

Thus, Slave To The Rhythm was finally complete and the single - the ‘slow version’ - was released in the UK in the Autumn of 1985, a whole year after recordings began. It was a top ten hit across Europe but disappointingly stalled at number 12 in the UK. Also, remarkably, Slave To The Rhythm never made the US Official Billboard Hot 100.

All in all, a surprising and anti-climatic 1985 outcome for a track that has become such an enduring classic since.

In a further twist, despite being nominated for video of the year at the 1986 MTV Music Awards, the video for Slave To The Rhythm actually features zero new footage of Jones, the entire creation instead being a series of clips from previous videos carefully cobbled together by (Jones’ boyfriend at the time) Jean-Paul Goude, most notably the footage from her documentary A One Man Show and her appearance in a South American advertisement for the Citroën CX 2 in which she drives out of (and back into) her own mouth…

Instead, we were treated to a legendary TV appearance: Jones famously appeared on UK chatshow Wogan - her only TV promo for the single’s release - during which, for the duration of the performance, she wore an ornate bag over her head, only removing it at the final climactic moment: “Heeeere’s Grace!…”

Then - acing even this act of insanity - who could forget the real highlight of the Queen’s Jubilee celebrations, 27 years later in June 2012: Grace Jones performing Slave To The Rhythm in front of Buckingham Palace while hula-hooping. Keep it up!