George Lois, a Madison Avenue ad maven who in the 1960s injected counterculture ethos into Esquire magazine’s covers, wounding boxer and anti-war activist Muhammad Ali with arrows and drowning Andy Warhol in a can of Campbell’s soup to depict the collapse of avant-garde art, has died aged 91.

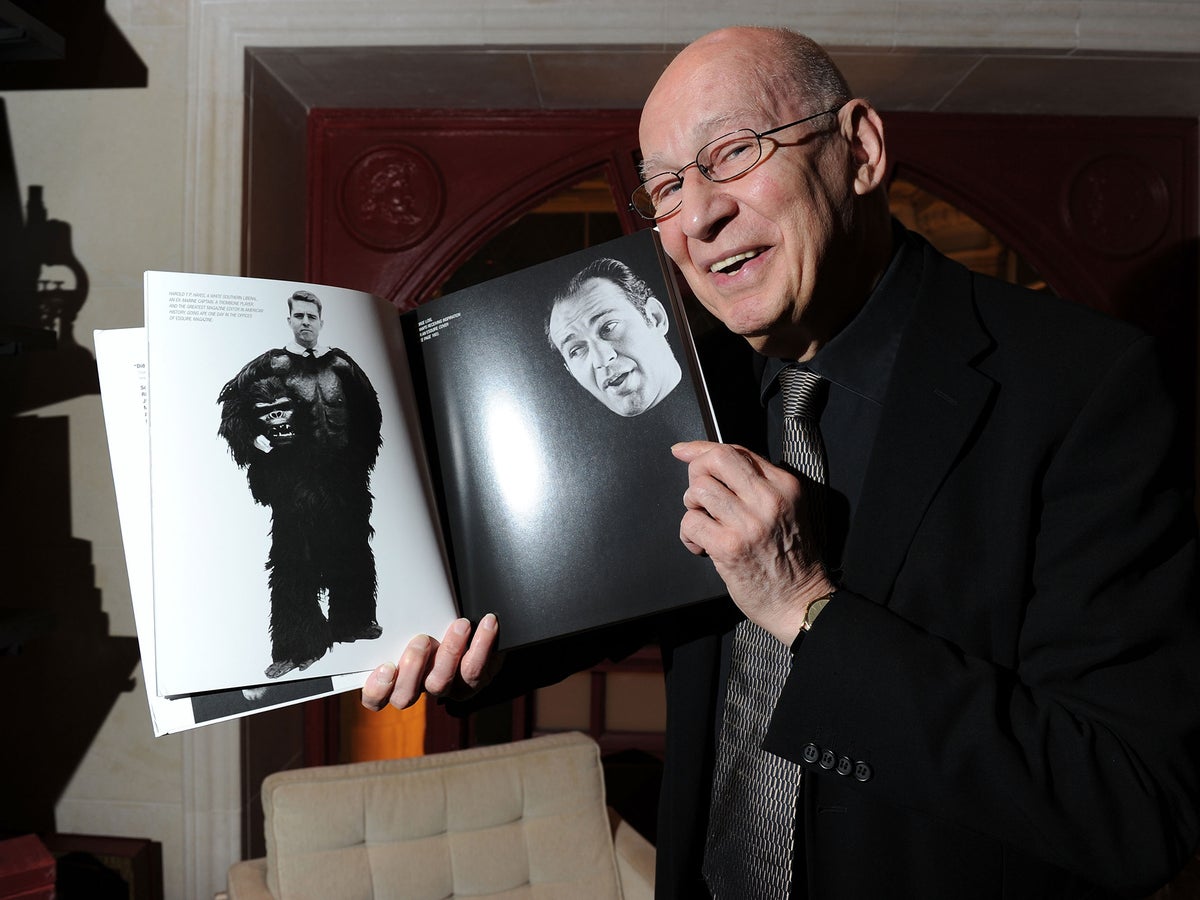

Though Lois designed groundbreaking ad campaigns for brands such as Stouffer’s, Xerox, Tommy Hilfiger and MTV – his “I want my MTV” commercials and posters were a staple of 1980s culture – his Esquire covers, the subject of an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art, were considered his magnum opus.

Working with photographer Carl Fischer, Lois depicted Ali, who had been convicted on draft evasion charges for refusing to fight in Vietnam, as the martyr Saint Sebastian in black and white boxing trunks – “a combo of race, religion, and war in one image,” Lois later said.

He put a halo over the head of Roy Cohn, chief counsel to senator Joseph McCarthy during his investigation into communist activity. In 1963, as racial tensions flared, he put a Santa Claus hat on boxer Sonny Liston for the December cover, angering “half the country”, Lois later said, and causing the magazine’s circulation director to ask Esquire editor Harold Hayes, “What the hell are you trying to do to us?”

Lois’s most shocking cover was of William L Calley Jr, the Army lieutenant court-martialed and convicted in the brutal My Lai Massacre, smiling in uniform with Vietnamese children sitting on his lap. To get him into that pose, Lois told Calley about his own experiences fighting in the Korean War.

“I won him over,” Lois told New York magazine in 2010. “And the kids just looked at the camera, and I said, ‘Calley, give me a big s***eating grin!’ And he did it. It ran and, I’m telling you, people went crazy in America.”

Which was precisely his intent as an art director.

“My kind of art has nothing to do with putting images on canvas,” Lois said told an audience at a Miami Beach design and advertising event in 2014. “My concern is with creating images that catch people’s eyes, penetrate their minds, warm their hearts, and cause them to act.”

To do so, he said, “I’ve had to shove, push, cajole, persuade, wheedle, exaggerate, manipulate, flatter, be obnoxious, occasionally lie, and always sell.” Throughout his career, he told stories about those methods with considerable, if not questionable, zeal.

In one story, it is 1959 and Lois is a young ad man with the Goodman’s matzot account. He designed a poster in a pop-art style with a colossal piece of matzoh under huge Hebrew script that translated to “kosher for Passover”. Goodman’s executives hated it.

“The owner was about 92 – all he knew how to do was say no,” Lois told New York magazine in 2003. “So I said, ‘Let me go out and sell it to them.’ That never happened back then – they just didn’t think that way. Back then, they wouldn’t let the art director go sell the job.”

So off he went to the Goodman office building in Long Island City. “I’m getting nowhere,” Lois recalled. “So finally, I had to do something.” He opened the window and stepped out onto the ledge. “You make the matzos,” he told Goldman’s owner, “I’ll make the ads.”

“Come back in, I’ll run it already,” the owner yelled.

“That became a famous story on Madison Avenue,” said Lois, who told it in his 1977 book The Art of Advertising. In a review headlined “Flaunting It”, New York Times book critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt wrote, “George Lois may be nearly as great a genius of mass communication as he acclaims himself to be.”

George Harry Lois was born 26 June 1931, in New York City and raised in the Bronx with two sisters. His father owned a flower shop. His mother was a homemaker. Being of Greek heritage made him a target in the neighbourhood. “I had a fistfight with every kid on my block,” Lois told New York magazine. “I got about 15 broken noses to prove it.”

But Lois also recalled being picked on because he “was always drawing, and I always had an artist portfolio with me”.

“Since I was a youngster in public school, I lived to draw, design, rearrange things,” said during his Miami Beach speech. “I could draw better, design better, sculpt better, paint better, do better in history of art courses, than anyone in school.”

He graduated from Manhattan’s High School of Music and Art in 1949 and then attended the Pratt Institute, where he met Rosemary Lewandowski on the first day of class and married her in 1951. She died earlier this year.

Lois left Pratt after a year, taking a job with New York designer Reba Sochis. After serving in the Korean War, Lois worked at several Madison Avenue firms, including Doyle Dane Bernbach, which he left with several colleagues in 1960 to start Papert Koenig Lois.

In 1962, Hayes, Esquire’s editor, asked him to help with the magazine’s covers, which were sober and boring. “The cover should make a statement, tell readers not only what that issue is about but what Esquire is about,” Lois told Hayes, according to Carol Polsgrove’s history of the magazine. “One cover would build on another, until people understood: this was a great magazine.”

Lois’s covers often resulted in complaints from readers, but Esquire stuck by him as the magazine became one of the hottest titles on newsstands, with the writing of Gay Talese, Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe, among other rising literary greats, filling the inside pages. Lois’s big personality grated on some of his Esquire colleagues, who thought he took too much credit for work that was actually more collaborative than he let on. He left the magazine in 1973 amid slowing newsstand sales.

Lois is survived by his son Luke and two grandsons. Another son, Harry, died in 1978.

Late in life, Lois was often asked about the authenticity of the hit television show Mad Men, an AMC drama about Madison Avenue executives in the 1960s. In 2013, interview with Newsweek, he referred to the show as human excrement, saying the characters – including Don Draper – were “no-talent bums”.

The show, he wrote in a CNN article, “is nothing more than the fulfilment of every possible stereotype of the early 1960s bundled up nicely to convince consumers that the sort of morally repugnant behaviour exhibited by its characters – with one-night-stands and excessive consumption of Cutty Sark and Lucky Strikes – is glamorous and ‘vintage’.”

Lois had a loftier self-image.

“By far the most thrilling” moment of his career, he told the Associated Press in 2008 during the MoMA exhibit of his Esquire covers, was seeing his work displayed at the museum. “I have always seen myself as an artist,” he said. “And this is the Museum of Modern Art. And I am an artist.”

George Lois, art director and designer, born 26 June 1931, died 18 November 2022

© The Washington Post