“Human life is limited, but I would like to live forever,” read the note Yukio Mishima left on his desk shortly before he left home for the final time.

Mishima, who would have turned 100 today, often touted as a potential Nobel Prize winner, was one of the most acclaimed Japanese writers and seductive prose stylists of all time. He is also one of the most controversial figures in Japanese history, due to his ultra-nationalist politics, reactionary proclamations – and shocking death by ritual seppuku (suicide) after he led a failed coup attempt.

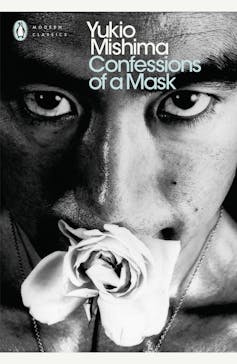

Mishima was first catapulted to literary stardom with his semi-autobiographical second novel Confessions of a Mask (Kamen no Kokuhaku) (1949), set against a pre-war backdrop marked by imperialistic fervour and right-wing extremism, and featuring a gay protagonist.

But he worked across nearly every genre: fiction, drama, poetry, autobiography, criticism. He also threw himself into film, music, dance, bodybuilding and martial arts.

Mishima’s work and unusual life story has inspired artists like filmmaker Paul Schrader, who wrote Taxi Driver, musician Richey Edwards of the Manic Street Preachers, and cultural icon David Bowie. They were drawn to his finely wrought and transgressive explorations of beauty, violence, eroticism and death.

Bowie, in particular, was heavily influenced by Mishima’s performative approach to art and existence. Bowie name-checked Mishima in the lyrics of one of his last songs and famously slept under a portrait of the author, which he painted in 1977.

Over time, Mishima grew increasingly disillusioned with the post-war trajectory of Japan, which he believed had forsaken its traditional values in favour of the hollow promises of Westernisation and globalisation. This shift, he argued, was symbolised by the demotion of the emperor from divine figurehead to a mere ceremonial symbol in an increasingly prosperous, democratic state.

Convinced the Japanese spirit was in terminal decline, he turned to traditionalism and nationalism. In 2025, with nationalist rhetoric and debates about cultural identity in the news, Mishima’s concerns about the erosion of tradition, problematic as they are, feel strikingly relevant.

An audacious attempted coup

On the morning of November 25 1970, just after completing the final instalment of his magisterial The Sea of Fertility (Hōjō no Umi) novel cycle, Mishima and four members of his private militia, the Shield Society (Tatenokai), staged the audacious coup attempt that would end in his death.

Mishima was carrying an attaché case and an antique samurai sword when he arrived at the Japanese Self-Defense Forces in Ichigaya, Tokyo. He had arranged to meet with General Kanetoshi Mashita, the commander of the Eastern Army.

After they exchanged pleasantries, the author and his young acolytes overpowered Mashita, taking him hostage and barricading themselves in his office. Mishima demanded the general summon the thousand-strong garrison stationed at the base, to assemble in the courtyard beneath Mashita’s office.

His goal was to inspire the soldiers to rise up against Japan’s post-war government, overthrow its democratic constitution and restore the emperor to his pre-war position of divine authority.

Stepping onto the sun-drenched balcony, Mishima, dressed in the brown uniform of the Shield Society and sporting a headband adorned with the symbol of the Rising Sun, unfurled a written manifesto and began to speak. But the crowd below drowned out his exhortations with jeers and laughter.

Crestfallen, he retreated back into the building. Taking off his watch and most of his clothes, he started, with the assistance of his followers, to prepare the stage for his premeditated – and carefully choreographed – final act.

Kneeling down, Mishima picked up a foot-long dagger and drove it deep into his stomach. Standing behind him was 25-year-old Masakatsu Morita, tasked with severing Mishima’s head from his body, in accordance with the traditional samurai ritual of seppuku. The grisly task finally completed, Morita also died by suicide.

Mishima’s death shocked the world. Salacious tabloids speculated wildly about the more intimate details of Mishima’s relationship with Morita. The nation’s scandalised leaders quickly issued statements condemning the world-famous author’s militancy. The Japanese literary community distanced itself.

Meanwhile, interested onlookers tried to make sense of it all. Why had Mishima done it? What was he hoping to achieve?

Child prodigy

Yukio Mishima was born in Tokyo on January 14 1925. His birth name was Hiraoka Kimitake. Something of a child prodigy, he was educated at the prestigious Peers School (Gakushūin), and graduated from the University of Tokyo with a law degree. After a brief stint working at the Ministry of Finance, he set his sights on finding fame as a writer.

Mishima’s literary aspirations can be traced back to his childhood. He began writing poetry at the age of six. By the time he hit his early teens, Mishima, who took inspiration from classical Japanese poetry and modern Western writers like Oscar Wilde and Rainer Maria Rilke, had composed over a thousand poems, along with several short prose works.

His literary career began in earnest in 1944, with the publication of A Forest in Full Bloom (Hanazakari no mori), a collection of short stories. It was followed four years later by his debut novel, The Thieves (Tōzoku), about love and death in Japan in the immediate post-war period. Notably, it featured an introduction by Mishima’s sponsor and champion, Yasunari Kawabata, the first Japanese novelist to win the Nobel.

A hidden self and violent fantasies

Then, Confessions of a Mask made him a household name in Japan. It tells the tale of a young gay man, Kochan. Acutely self-aware, the precocious Kochan understands he is different. He emphasises artifice and performance:

Everyone says that life is a stage. But most people do not seem to become obsessed with the idea, at any rate not as early as I did. By the end of childhood I was already firmly convinced that it was so and that I was to play my part on the stage without once ever revealing my true self.

By the same token, Mishima’s narrator is more than happy to confide in the reader:

that is not the usual matter of ‘self-consciousness’ to which I am referring here. Instead it is simply a matter of sex, of the role by means of which one attempts to conceal, often even from himself, the true nature of his sexual desires.

Kochan’s sexual and psychological desires, he candidly reveals, often take on a disturbingly violent intensity. Earlier in the book, he admits to “delighting in imagining situations in which I myself was dying in battle or being murdered”.

These impulses persist throughout Kochan’s childhood and adolescence. In September 1944, the now 20-year-old Kochan, having graduated from university, is sent to work in a factory. He explains, in characteristically expansive prose, that the factory

operated upon a mysterious system of production costs: taking no account of the economic dictum that capital investment should produce a return, it was dedicated to a monstrous nothingness. No wonder then that each morning the workers had to recite a mystic oath.

It takes a moment for the reader to appreciate what Kochan, who is taken aback by what he sees, is getting at:

In it all the techniques of modern science and management, together with the exact and rational thinking of many superior brains, were dedicated to a single end – Death.

He continues:

Producing the Zero-model combat plane used by the suicide squadrons, this great factory resembled a secret cult that operated thunderously – groaning, shrieking, roaring […] it did in fact fact possess religious grandeur, even to the way the priestly directors fattened their own stomachs.

This unsettling, morbid passage is typical of Mishima. It offers an unflinching critique of industrialised modernity, simultaneously presenting the factory as a quasi-sacred, swollen and explicitly sexualised sort of space.

Not long after this, Kochan admits to “having completely lost the desire to live”. He takes solace in being “surrounded by such a bountiful harvest of so many types of death”, including in “an air raid”, “military service”, or “from disease”.

Despite this, he survives the war. Yet his survival feels almost like a betrayal of his desires. He confesses a “feeling of being neither alive nor dead”.

While we need to be cautious when drawing direct parallels between fiction and the author’s life, Mishima, like many others of his generation, seems to have felt the same way.

Exposed to a heady concoction of wartime propaganda and emperor-worship, he struggled to make sense of what defeat meant for post-war Japan, and to come to terms with Emperor Hirohito’s abdication of divine authority.

These themes come to the fore in the title story of a new English collection of Mishima’s stories, Voices of the Fallen Heroes (Eirei no koe), published this month to mark his centenary.

A dangerous blend

As his dramatic and divisive actions on November 25 1970 demonstrate, Mishima fervently embraced the idea of a glorious militaristic past. In a very real, if unnerving sense, Mishima’s commitment to this vision culminated in his final, dramatic act.

During his lifetime, he was labelled “a sensationalist, a contrarian, an irrationalist, an egomaniac, a fake, a buffoon, a nihilist, a genius, a fascist, a madman”.

His life invites us to reckon with the intersection of art, politics and identity in ways still painfully relevant today. It also raises a host of related questions. Would he have been remembered as a towering figure in world literature if not for the manner of his death? I think he would, though others might disagree.

What we can say for certain is that Yukio Mishima is not just a literary icon – he is a cautionary reminder of the complex, sometimes dangerous relationship between creativity and fanaticism.

Alexander Howard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.