Ever been to a large sporting event, such as a football or baseball game with 60,000 screaming fans? What you don’t hear through the screams is a clicking sound in the chests of about 1,500 of these fans who have a heart valve disease. And it’s likely that one or two of those are sitting in your row.

Many of these people may, during the excitement of the game, feel that something is not right with their heart. But the problem doesn’t seem severe. So they ignore the sensation of feeling faint or weak, and they continue watching the game.

During a checkup with their primary care physician, however, their doctor might hear the “click” inside their chest. That’s a sign of a potential problem with their heart valves. After they follow up with a cardiologist, they are often diagnosed with a common heart valve disease called mitral valve prolapse. Although one of the most common cardiovascular diseases, doctors have not understood the causes of this disease.

I have been studying heart valve disease for over 20 years and initially became interested in heart valves after I learned that members of my own family had suffered from mitral valve prolapse. This led me to work with Roger Markwald, a pioneer in the field of cardiac valve development. Together, we have been part of large collaborative network to study heart valve disorders. One of these international consortiums has now discovered a genetic cause of mitral valve prolapse.

What is mitral valve prolapse?

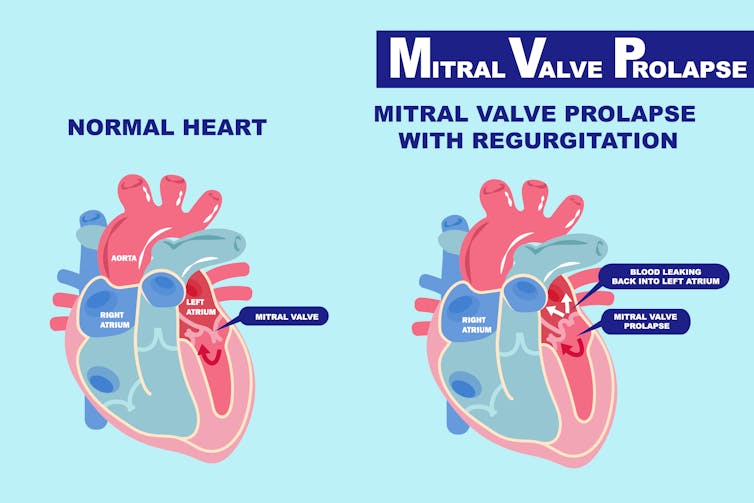

The heart is a complicated organ, and there are many things that can go awry. In mitral valve prolapse, the two mitral valve leaflets, or flaps, are located on the left side of your heart and are positioned between the left atrium and left ventricle. These valves function as one-way doors, enabling blood flow in only one direction.

In patients with mitral valve prolapse, the doors become warped and can’t quite close all the way. As a result, blood can flow back into the left atrium and not out to the rest of the body where it should be going. This is called regurgitation. The more regurgitation a person has, the higher the risk of additional complications, including death. The condition affects one in 40 people and is one of the most common cardiovascular diseases worldwide.

Surgery to repair the mitral valve is the fastest-growing cardiovascular intervention in the United States, increasing by more than 40% since 2011.

Embryonic origins of disease

While mitral valve prolapse is common, doctors have not known its causes. It wasn’t until today that I and my colleagues reported a genetic and biological trigger for the disease.

Tackling this complex clinical problem required an international team of geneticists, cardiologists, echo-cardiographers and surgeons all collaborating to identify genetic and molecular causes for mitral valve prolapse in a multigenerational family of 43 members, 11 of whom suffered from this disorder. Our team also used data from more than 1,400 unrelated patients with mitral valve prolapse.

Using the DNA from the members of the large family, I and my colleagues identified a mutation in a gene called DZIP1. My team members genetically engineered mice with this exact mutation to provide a way of understanding how and why the disease begins and how it progresses. The models fully recapitulated the human disease and, to our surprise, revealed that mitral valve prolapse – which is normally identified in the aging population – originates during embryonic development.

This means that the blueprints for how these heart valves form in mitral valve prolapse patients are altered from the outset; it’s like a house being built with faulty bricks. Over time, the structure of such a house begins to fail.

A biological explanation

Our group has found that the “bricks” of the heart valves, known as valve interstitial cells, require tiny hair-like structures called primary cilia to form and function properly. The cilia function as cellular antennae to receive signals from the surrounding environment, much like an antenna on top of your house. However, in many patients with mitral valve prolapse, these antennae are absent or defective, and the cells lose their ability to sense their surroundings.

As a consequence, the normal structure of the valve becomes altered and over time leads to mitral valve prolapse.

So, how does this finding help physicians treat mitral valve prolapse? Well, it’s going to take some more time and more funding to figure that out.

Surgery is currently the only effective curative option for mitral valve prolapse. But now that the first animal model for this disease has been created that is based on genetic mutations found in patients, scientists can begin testing how drugs can stop the disease from progressing or reverse the defects that happened early in life.

Russell Norris receives funding from the National Institutes of Health, American Heart Association and the Leducq Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.