Gene Pesek viewed the world as if he were a camera.

“I see photography no matter where I am,” he once said in an interview with videographer Jim Quattrocki, whose career Mr. Pesek helped inspire by giving him a camera when he was 6. “I see pictures. I can be driving on [the] Dan Ryan and looking straight ahead, and I’ll see a picture.”

Mr. Pesek chronicled the beautiful and the bestial in a nearly 40-year career as a Chicago Sun-Times photographer. Some days, he’d be assigned to shoot movie stars or spring flowers. Other times, he shot crime scenes, plane crashes and political conventions.

He died May 16 at the Matteson home of his daughter Debra Wallace. He was 95.

“He could do anything,” said Rich Cahan, an author and former Sun-Times picture editor who worked with him.

His work was shown at the Art Institute of Chicago.

“He was very meticulous in his craft and the way he lit things,” said former Sun-Times photographer Bob Black. “I used to ask him, ‘How’d you do that?’ He was a master.”

To capture a memorable moment, Mr. Pesek might go up in a helicopter with the doors wide open. Or he’d board an amusement-park ride — and ride it backward to capture the look on the faces of those behind him.

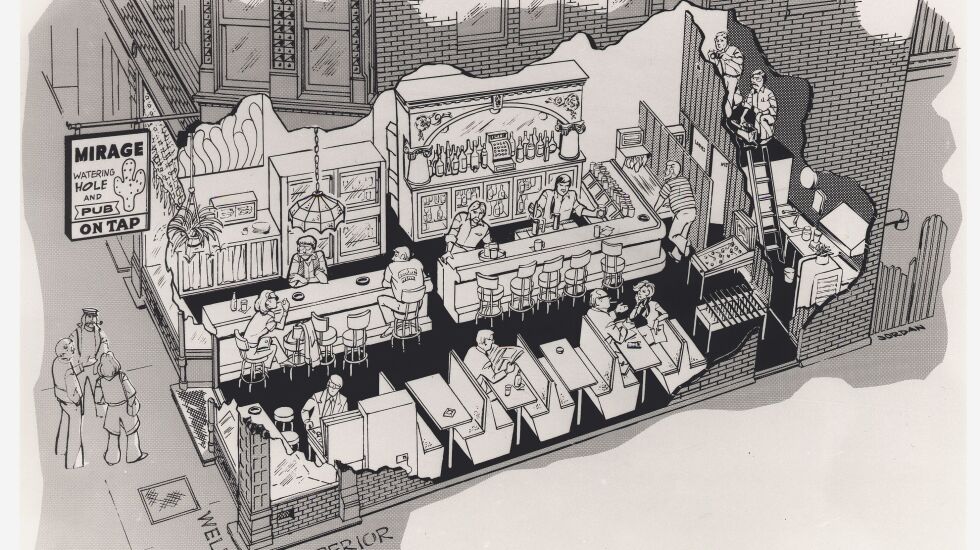

One of Mr. Pesek’s proudest achievements was working on a blockbuster investigation in the late 1970s involving a team of reporters from the Sun-Times and the Better Government Association that he couldn’t talk about while he was working on it. He and fellow photographer Jim Frost shot undercover photos capturing shakedowns for bribes at the Mirage tavern, a dive bar at 731 N. Wells St., that the Sun-Times bought to catch and expose corruption.

The resulting stories by Sun-Times reporters Zay N. Smith and Pam Zekman exposed kickbacks, tax fraud and government inspectors who ignored problems in exchange for a cash-filled envelope left atop the bar.

“It was such an incredible story,” Mr. Pesek told Quattrocki. “They said, ‘We have a special assignment for you. You can take it, it may be dangerous, we don’t know. But if you don’t want it, we’re not gonna to tell you about it. If we tell you about it, you gotta take it.’ So I says, ‘Well, you know, it sounds good.’ I said: I’ll try.”

Working on the Mirage investigation, he and Frost pretended to be repairmen in an effort to avoid suspicion. They’d hide their cameras in their toolkits.

“He would put on overalls and a flannel shirt” to work at the Mirage, according to his daughter Pamela Tietz.

Frost said he cut a hole in a wall and covered it with a vent in order for him and Mr. Pesek to secretly shoot photos.

“I took it home, and I beat it all up because it was not a pretty place,” Frost said, “and a shiny vent would have been out of place.”

He said he and Mr. Pesek understood how important it was for them to document the corruption.

“The whole thing was hanging on me and Gene in a big way,” Frost said.

“The fact that Gene and Jim actually had pictures of fire inspectors taking a bribe and had photos of what was going on made the series three-dimensional,” Cahan said. “It was the key to the whole series.”

Young Gene grew up near 70th Street and South Lawndale Avenue. His father was an architect, which influenced his way of seeing the world’s lines and patterns, he said in the interview. For his graduation from Davis grade school, his dad gave him a gift: a box camera.

He went to Kelly High School, where he met Dolores “Duckie” Cook, who would become his wife of 61 years.

When he tried out for the football team at Kelly, his daughter said, “The coach told my dad he’d be much better off in the Camera Club.”

During World War II, he served in the Army Air Forces in Hawaii, according to his family.

Working for the Sun-Times in an age long before GPS and step-by-step directions on smartphones, Mr. Pesek had a knack for getting around quickly, Cahan said.

“He knew the city inside and out,” he said. “You had to know the fastest way to events.”

Mr. Pesek often shot cover photos for Midwest, the newspaper’s old Sunday magazine.

For Mr. Pesek, photographing celebrities was just part of the job. Not that he always knew who it was he was making pictures of. Once, he told his daughters he was going to be shooting a band named Twigs, or maybe it was Branches.

“It was Styx,” Tietz said.

Mr. Pesek retired in 1991 after more than 38 years at the Sun-Times, save for a brief period when he left to operate his own photo studio.

Mr. Pesek and his wife volunteered at the Animal Welfare League in Chicago Ridge, and they ended up taking in dogs at least five times, according to their daughter Sandra Vail.

Rocky the beagle was his special dog, though.

“If my dad had coffee cake,” Tietz said, “Rocky had coffee cake.”

Once, he and his wife rescued a sparrow that had fallen from a nest. They fed it with an eyedropper. When they tried to set it free, it kept flying back to them. So they kept it and named it Chicken. The bird lived for five years and would perch on Dolores Pesek’s shoulder while she cooked dinner.

They enjoyed relaxing together.

“They’d sit outside and drink Hilty Diltys,” a cocktail, their former neighbor Rosemary Quattrocki said.

Mr. Pesek’s wife died in 2010. In addition to his daughters Debra, Sandra and Pamela, he is survived by eight grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

Mr. Pesek preferred to write notes on paper plates rather than on paper. So, at his funeral service on Tuesday, his daughters placed paper plates in his casket bearing messages they’d written, saying they loved him.