A deeply satisfying, revelatory revival on so many levels, director Marianne Elliott’s Tony Award-winning production of Stephen Sondheim’s marriage-contemplating musical “Company” — now making an early stop in Chicago on a new tour — freshens a 50-year-old show to the point that many have claimed, as I would, that this is the best version yet.

The headline is that the lead character changes from male Bobby to female Bobbie. Sondheim contributed to the tweaks, fully recognizing the benefits of a new perspective on a show first produced in 1970. The gender swap works so well that it solves what has always been the show’s major weakness, a central character without much personality, a likable but shallow bachelor primarily present to spur judgments on and from the swirl of married friends around him.

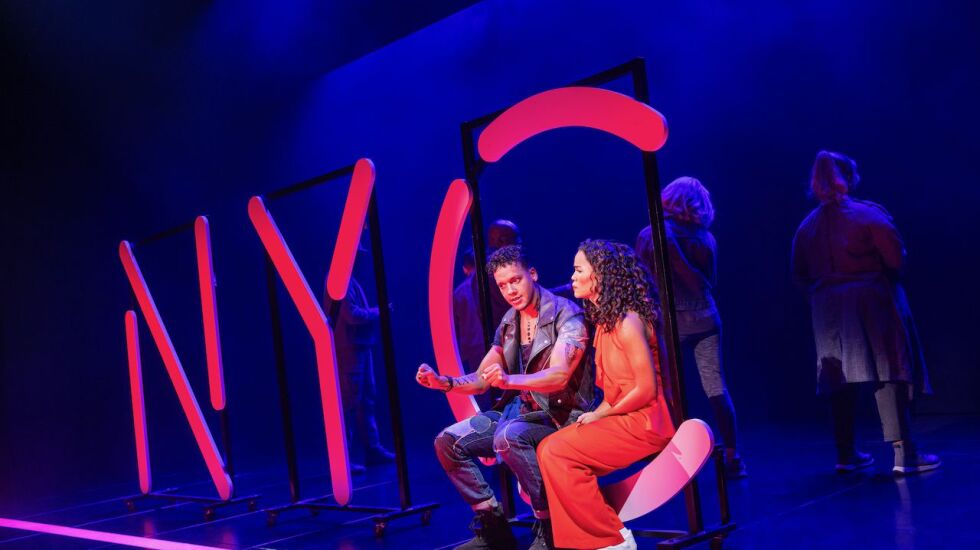

It’s not just that changing our him to her flips some miraculous meaning switch — although at times it does, given that expectations of women to marry, and have babies, exceed that of men by orders of magnitude. It’s also that Elliott’s production and this tour’s terrific Bobbie — Britney Coleman, who understudied the role on Broadway — invest her with a playful personality and take us deep inside her head, depicting her internal battle about life decisions such that the show vibrates with an emotional reality along with a sense of wit.

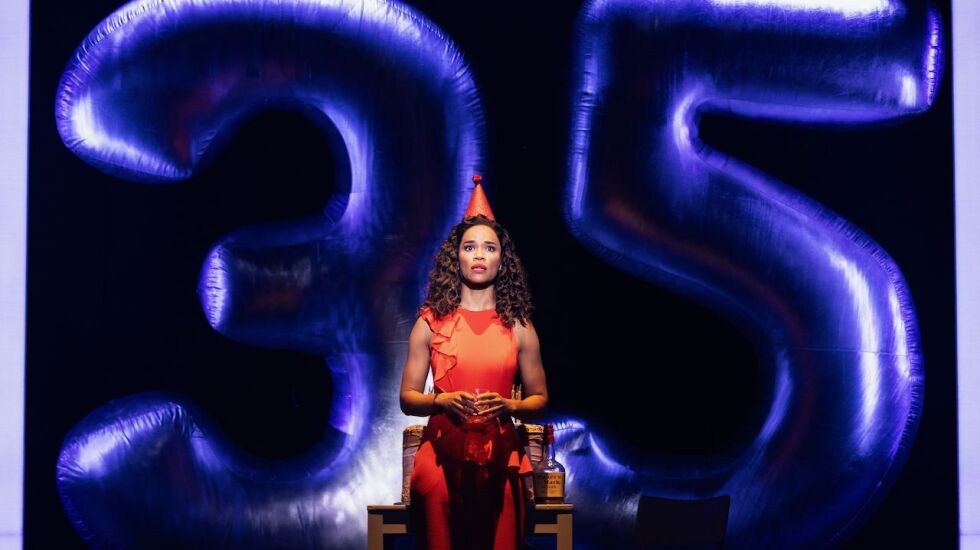

The show begins with and returns frequently to a surprise party for Bobbie’s 35th birthday. The other sequences are sketches about married life, taking Bobby from one couple to another. The form, a “concept musical” without a linear plotline, was highly original, and reflected both its era of variety shows and the initial source, a collection of short plays by book writer George Furth.

Set and costume designer Bunny Christie deserves a great deal of credit here. She gives us a series of box-like rooms for different sequences, each framed by light, suggesting moving snapshots.

The key one, a confining room in Bobbie’s New York City apartment, comes in different sizes, at one point in visually amusing miniature. When enlarged to oversize, the space fits giant balloons shaped like the numbers 3 and 5 that then chase Bobbie around. Throughout, you won’t forget that Bobbie is turning 35 because various breadcrumbs remind you, such as a clock in her bedroom reading 3:05.

That bedroom provides the space for a breathtakingly ingenious dance-like dream sequence where Bobbie, after sex with one of her three beaus (all now male), imagines married life. The other female cast members enter clothed in Bobbie’s recognizable red, depicting her simultaneously as coffee-getter, cleaner-upper, baby-carrier and sex-averse mother. It’s the complete expression of why Bobbie fears marriage, the force that drives the show and makes everything make sense, and yet that we usually have just had to take for granted. It also says something about the canniness of this show that I can’t identify the line between Elliott’s staging and Liam Steel’s choreography.

Other surprises here emerge from changes to the music (Joel Fram is the music supervisor and vocal arranger). Although some are required when songs change from male to female or vice versa, that alone doesn’t describe how the show sounds as fresh as it plays.

The highlight in this realm is “Another Hundred People,” about the social isolation of the biggest of American cities. Performed beautifully by Tyler Hardwick, the song comes across with smoothness and empathy, capturing the happy/sadness of so much of Sondheim.

There are too many musical highs in this show to mention. One of Sondheim’s best scores, it shines here from the emotional, and often comedic, vitality, of an excellent ensemble. For the comic, there’s Act II opener “Side by Side by Side,” for which the cast puts on too-small party hats and Coleman skillfully mixes clownishness and desperation. And then there’s the always-a-showstopper-but-especially-here panicked patter song “Getting Married Today,” performed with neurotic aplomb by Matt Rodin in another perfectly conceptualized gender switch, and which also features characters’ delightful emergence from unexpected spots.

For the feels, there’s certainly Coleman’s finisher “Being Alive,” as well as “The Ladies Who Lunch,” a cynical song delivered by Judy McClane’s boozy, much-married Joanne after several too many vodka stingers. In this case, when she sings “And here’s to the girls who just watch/Aren’t they the best?,” she stares hard, even accusatorially, at Coleman’s Bobbie, making this number more dramatic than it’s ever been.

So, to sum up, this version of “Company” makes the show funnier, more meaningful, more relatable, and much more affecting.

As Joanne would say, “I’ll drink to that.”

.jpg?w=600)