Just say it. Spit it out. Abolish GCSE. It has nothing to do with young people or their advancement. It has everything to do with quantifying, measuring, controlling and governing their preparation for life.

Last year, Prof Becky Francis was asked by the education secretary, Bridget Phillipson, to draw up proposals for the curriculum in England’s secondary schools. In her interim report out this week she recognised the challenge, but then took fright.

Francis took up the charge that England’s schools are obsessed with exams. She “feared” that they “overly stress” children and prioritise academic subjects. These are not fears, but facts. Anyone reading post-Covid figures about the mental health of young Britons might wish to emigrate. A soaring one in five schoolchildren now report mental illness. A fifth of pupils in England are persistent truants. School suspensions and expulsions last year were a full third up on the previous record year.

Overly stressed is an understatement. Pupils in England sit twice the hours of exams as do Irish students – and three times the Canadian figure. The gods of GCSE help schools order their classes and assess their teachers – and give ministers a boost in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Pisa World Cup in maths. Pisa’s most truly awful league table is for European pupils’ sense of “life satisfaction”. Among 15-year-olds, the UK comes bottom.

But GCSE’s biases are gross. It places English and maths above all forms of education, yet 40% of pupils fail those subjects, and most fail their retake. Without a maths GCSE, you supposedly cannot become a nurse, teacher or police officer. This is crazy. There is no prize for guessing which jobs now have gaping vacancies.

Just as the chip renders obsolete a need to know how engines work, so computers and soon artificial intelligence have rendered maths obsolete. In both cases, the subject is the pursuit of a tiny minority. It is computers that all pupils should study and learn how to use, rather than be suspended or accused of cheating for doing so. Making them learn maths is like teaching them to swim but banning the use of water. Yet to say this in education circles – I began my career in London’s Institute of Education – is like swearing in church.

The most telling chart in the Francis report is of what today’s parents and pupils themselves want from schools. Overwhelmingly, both asked for the opposite of what schools are giving them. Their top subjects were personal finance, digital and computing, creative activities, problem-solving, employment, interviewing and debating skills. All were favoured ahead of academic subjects. GCSE might offer a choice of hobby. Pupils wanted help with life’s challenges. They wanted a vocation.

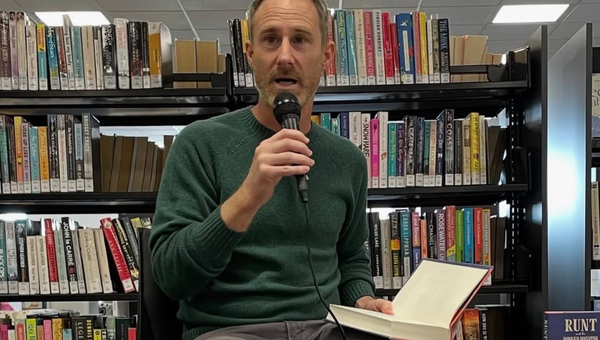

It is a feature of this list that these subjects are all hard to measure. That is clearly the system’s chief objection to them. As the dissident teacher Sammy Wright writes of the cult of the exam in his Exam Nation, GCSE rules all because it is the basis of a school’s public face and pupils are therefore told, over and again: “You need good grades to get on in life.” Exam performance dominates teenage morale. He points out that GCSE English once had 20% of its marks devoted to the essential skills of speaking and listening. When this proved hard to measure, it was simply dropped, demoting the aspect of English that was “most relevant to the widest range of kids”.

Mental illness among young people – however questionable its definition – needs the attention of both parenting and teaching. Francis has drawn attention to exams as a contributory factor, but she is too kind to GCSE. A more radical challenge came from last year’s Oracy Commission, and its plea for instruction in articulation, in speaking, debating and team working, as an antidote to pupils’ mobile phone addiction. Francis ignored this convincing call.

Of course, assessment is needed to ensure schools are up to the mark. Teachers need training in what pupils – and their parents – most need to prepare them for life. Means must be found to ensure this is supplied. But the cult of the exam is not the answer. The present system patently causes harm. Schools should not do that. In her final report, Francis should have the guts to kill GCSE and start again.

Simon Jenkins is a Guardian columnist