Food prices in the UK are at their highest for 15 years and something similar is happening in almost every country around the world.

The situation is set to get worse as high fertiliser prices, and resulting lower yields from reduced use, may cause further food inflation in 2023. My co-authors and I recently published research in Nature Food which suggests these price rises will lead to many people’s diets becoming poorer, with up to 1 million additional deaths and 100 million more people undernourished.

This isn’t just happening because of reductions in food exports from Ukraine and Russia, which are less of a driver of food price rises than feared. And unlike previous food price spikes higher food prices may be set to last. This could be the end of an era of cheap food.

Disruption to food and fertiliser markets

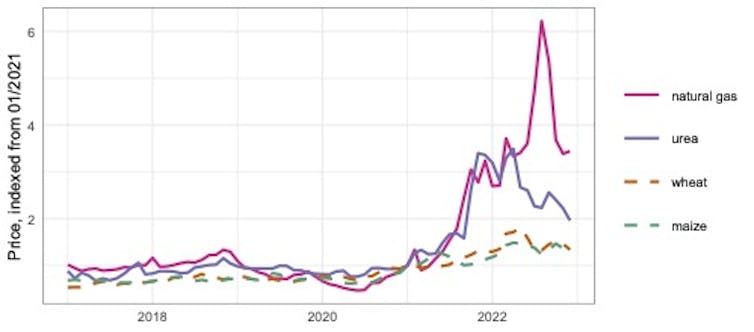

While commodity prices have come down from the peaks of mid-2022, they remain high. At the end of 2022, the global price of maize was up 29% and wheat up 34% since January 2021. This has fed food price inflation, for example in the UK 16.8% inflation in the year to December 2022. Two of the main drivers for these increases are higher energy prices and disruptions to international trade, both with strong links to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Sanctions and other war-related trade disruptions were high profile, yet appear to have diverted attention away from the more important issue. Energy prices affect food prices directly by increasing the costs of agricultural inputs such as fertilisers, since natural gas is used to make nitrogen fertiliser and accounts for 70%-80% of the total cost of fertiliser production. Additionally, farmers may respond by using less, which leads to lower crop yields, pushing up food prices further.

From 2021 to 2022, urea (a common nitrogen fertiliser) almost doubled in price and natural gas more than doubled, although both are below their mid-2022 peaks. These changes led to cuts in nitrogen fertiliser production as plants became uneconomic, particularly in Europe where 70% of production capacity has been curtailed.

Impacts in 2023 and beyond

In our study, we attempted to better understand how energy and fertiliser price rises and export restrictions affect future global food prices. And we wanted to quantify the scale of harm that hikes in the price of food could have on human nutritional health and the environment. We did this using a global land-use computer model (LandSyMM) which simulates the effects of export restrictions and spikes in production costs on food prices, health and land use.

We found that surging energy and fertiliser prices have by far the greatest impact on food security, with reduced food exports from Ukraine and Russia having less impact on prices. The combined effect of export restrictions, increased energy and fertiliser prices could cause food commodity prices to rise by 81% from 2021 levels.

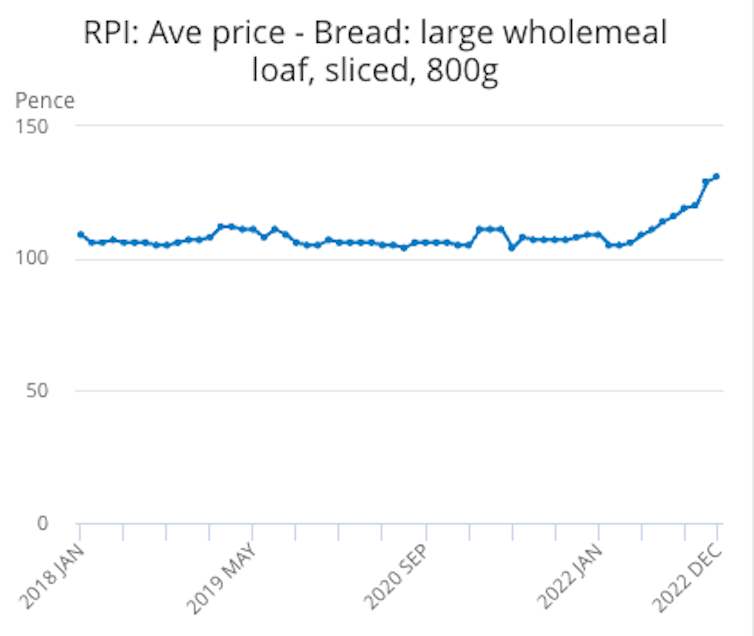

Such a rise would imply wheat prices increasing in 2023 by the same percentage again as they did in 2022. While the cost of wheat is only a part of the cost of bread, in the UK the average price of a large wholemeal loaf of bread rose from £1.09 at the start of the year to £1.31 at the end. If the inflation rate continues through 2023, that loaf would cost £1.57.

Export restrictions account for only a small fraction of the simulated price rises. Halting exports from Russia and Ukraine would increase food costs in 2023 by 2.6%, while spikes in energy and fertiliser prices would cause a 74% rise.

Too expensive to eat well

Food price rises will lead to many people’s diets becoming poorer, especially those with the lowest incomes. Our findings suggest there could be up to 1 million additional deaths and more than 100 million people undernourished if high fertiliser prices continue. The greatest increases in deaths would be in Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa and the Middle East, as people become unable to afford sufficient food for a healthy diet.

Our modelling estimates that sharp increases in the cost of fertilisers – which are key to producing high yields – would greatly reduce their use by farmers. Without fertilisers more agricultural land is needed to produce the world’s food. By 2030 this could increase agricultural land by 200 million hectares, an area the size of much of Western Europe – Belgium, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain plus the UK combined. This would mean lots more deforestation and carbon emissions, and a huge loss of biodiversity.

While almost everyone will feel the effects of higher food costs, it’s the poorest people in society, who already struggle to afford enough healthy food, who will be hit hardest.

Subsidising fertilisers may seem an obvious solution to a problem created in large part by the high cost of fertiliser. However, this just maintains a food system which has given us an obesity epidemic, left millions malnourished, contributes to climate change and is the main factor in the loss of biodiversity.

Targeted actions to ensure healthy and nutritious food is affordable for everyone may be more cost effective in reducing negative consequences from higher food prices and help to transform the food system to a healthier and more sustainable future.

Peter Alexander receives funding from UKRI.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.