When Vietnamese women fighters were operating the anti-aircraft guns that protected the Gulf of Tonkin in North Vietnam, and female guerillas were stalking the wild mountain ranges of the nation’s Central Highlands, American women were kept well away from the front lines of the Vietnam war.

There was no need for American women to fight because the draft meant there was a seemingly endless supply of young American men who could be sent to join the conflict in the Southeast Asian nation.

The United States was not alone – the armed forces of many nations were late in recruiting women for combat roles. For centuries women were thought to lack the qualities necessary for combat, and to this day many armies deploy female soldiers in minor support roles.

Even in Israel, where military service is mandatory for both sexes, there has been a marked reluctance to send women to fight on the front line. As recently as 2014, the Israel Defence Force admitted that fewer than 4 per cent of the country’s women soldiers were in combat roles, with most clustered in “combat support” positions.

Australia only lifted its ban on female combat soldiers in 2013, Britain even later, in 2016. In May 2019, the British Special Air Service (SAS) accepted its first female recruit, and this year, 28-year-old trailblazer Captain Rosie Wild was the first woman to pass the British Parachute Regiment’s gruelling selection process.

Even when they are recruited, women can be treated poorly. Indonesia’s virginity testing of female army recruits, ostensibly a health check, was reportedly still in effect as late as 2018.

In much of the world, entrenched ideas about the role of women have been slow to break down. “The idea of the female carer may be losing relevance today, just as the male protector is, but these gender roles still hold sway,” says social justice scholar and historian Dr Jessica Frazier, from the University of Rhode Island in the United States.

In terms of their numbers, and the power and authority they wield, women soldiers have long been vastly outranked by men on the front lines.

“Women are expected to be good wives and mothers who produce and care for male soldiers,” says Dr Ali Bilgic, a lecturer in politics and international relations at Loughborough University in Britain.

“Many Western democratic states are late to include women in the military.” Women, he adds, have traditionally been expected to be “emotional, protected, passive, domestic and apolitical”.

Occasionally, when there has been a desperate need to defend the homeland against alien invaders, women have picked up arms.

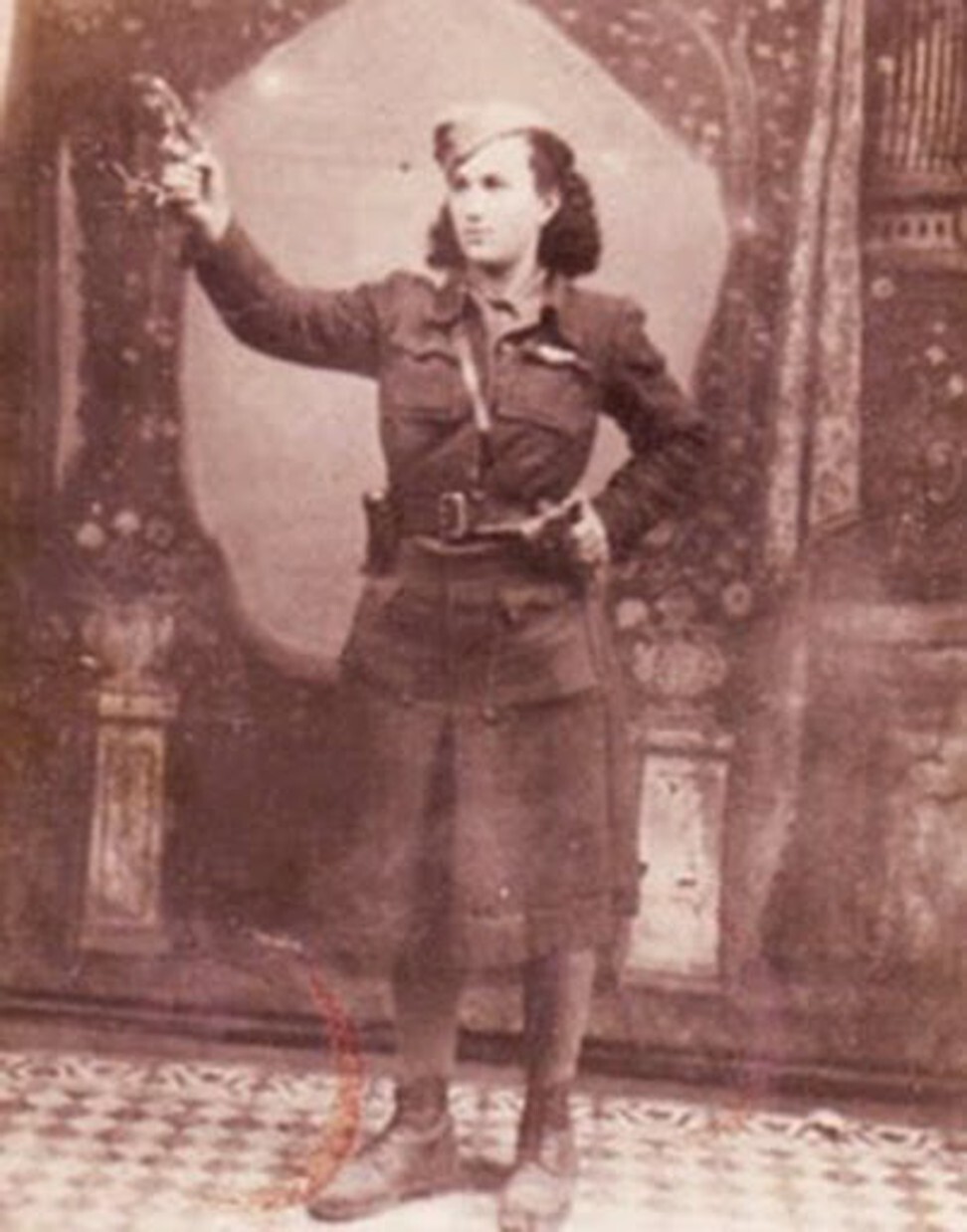

Sarika Yehoshua, also known as Sara Fortis, recruited and led a small, all-female group of partisans to fight German forces occupying the Greek island of Euboea in World War II. They used diversionary tactics to draw German forces away from areas that other resistance fighters planned to attack.

According to the Jewish Partisan Educational Foundation, the young Greek women burned down houses, killed Nazi collaborators and helped their male colleagues with missions for which the men were routinely given the sole credit. The Nazis sent an informer to try to capture Yehoshua, but it was her cousin who was arrested, raped and killed. She tracked down and killed the informer.

On the other side of Europe, in the same war, the Soviet Union’s Night Witches waged ferocious battle in the air. Supplied with flimsy wood and canvas aircraft, the “witches” were an all-female Soviet regiment of night bombers.

Their technique of idling engines to glide silently and undetected on the approach to their targets was likened by Nazis to the work of witches on broomsticks – hence the name. Their risky but effective strategy earned many of the women the title “Hero of the Soviet Union”.

The Women’s Protection Units (YPJ), an all-female, mostly Kurdish militia, have fought in the Syrian civil war, and have been described as “the women who terrify Isis”. By August 2017 there were estimated to be at least 20,000 women in the YPJ. They have attracted international attention for breaking down gender barriers in a very traditional part of the world.

Women soldiers have attributes that men lack. Those traumatised by war will talk to other women, even if they are in the military, when they might not talk to men.

Women soldiers can visit places where men are banned, and women are sometimes seen to be more conciliatory, willing to negotiate a solution that is acceptable to all parties, rather than to hastily take up arms and start fighting.

“Militaries that allow women to take on new roles in specialist military units, such as the American all-female units in Afghanistan that could enter female spaces and talk to local communities in new ways and gain new information, clearly add to military endeavours, including the ultimate endeavour to end conflicts,” says Frazier.

For their part, Vietnamese women fighters played a crucial part in the Vietnam war. At least 45,000 Vietnamese men and women died defending the Cu Chi tunnels, a vast network of underground passages in a part of what is today Ho Chi Minh City, and the women were seen as indispensable.

Small and agile, they could move swiftly through the narrow subterranean alleyways. They were famed for their skills at planting bombs and their ruthlessness in battle.

These Vietnamese women were driven by patriotism, but most of the fighters on the other side of the Vietnam war were drafted or coerced.

“It is also important to point out that for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) [to give then-communist North Vietnam’s its official name], female soldiers suited its propaganda purposes,” Frazier says. “Female soldiers symbolised the equality between men and women in North Vietnam and under communism.

“Much like during the Spanish civil war, feminists and other activists around the world pointed to the achievements of female soldiers in North Vietnam and imagined the DRV as a society that had achieved equality between men and women.”

Women resistance fighters are enshrined in Vietnam’s war art. “North Vietnamese women played an incredibly important role during wartime, particularly in defensive roles, such as manning anti-aircraft stations,” says Adrian Jones, owner of Witness Collection, an archive of Vietnamese war art. “Artists depicted them in relation to the important roles they played.”

War artist Trinh Kim Vinh contributed to the Vietnamese resistance in both of the nation’s wars in the 20th century. Her willingness to confront danger distinguished her as a resistance artist, particularly when she was a young woman during the First Indochina war, the battle against Indochina’s French colonisers.

Her daring extended into the Vietnam war – or the American war, as it is known in Vietnam – when she joined jungle operations to sketch soldiers, juggling that work with her duties as head of the drawing department at the Vietnam Fine Arts College.

“I was the only female artist of that time who dared to take field trips to paint,” she told Witness Collection researchers. “It was not easy to go to such places, but I was eager to go. Other people were afraid of bombs and bullets. I was young then, so I was afraid of nothing.”

In Phuoc Long, on the Cambodian border, war artist Vo Xuong painted a female nurse protecting a wounded soldier sheltering in a bunker. “The nurse and the soldier were inside a bunker; she picked up a gun and fought,” Vo Xuong remembers. “In wartime, nurses had to know how to fight.”

As for American women, they were finally admitted to US military academies in 1976, a year after the Vietnam conflict ended.