The afternoon of Friday, October 29, 1971 was an unseasonably warm one in Macon, Georgia. The air was thick with honeysuckle, and the leaves on the poplar and cherry blossom trees were still the stubborn green of summer. Houses along the sleepy streets were decorated with cardboard skeletons and witches for Halloween. Kids walking home from school were comparing notes on the costumes they were going to wear to go trick-or-treating: an astronaut; Fred Flintstone; a rock star.

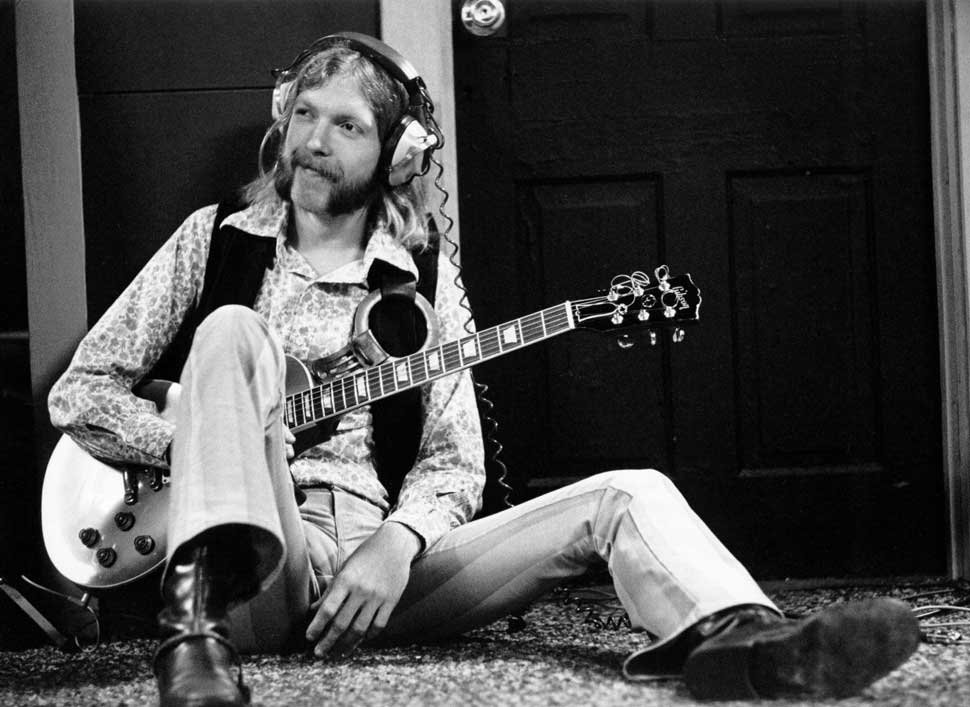

If they needed inspiration for the latter, they could have glanced up at the front porch of the funky three-story house at 2321 Vineville Avenue. Sitting there, carving a jack-o-lantern, was a real live rock star. With long, red, wispy hair hanging across furry mutton-chop sideburns, he leaned over the pumpkin and cut out a jagged-toothed mouth with a sharp knife.

His band’s manager would have had a fit if he’d seen that blade so close to those million-dollar fingers. But being careful was not part of Duane Allman’s make-up. As his nickname Skydog implied, Duane liked to fly fast and high. Whether playing a soul-searing slide guitar solo in front of 3,000 fans at the Fillmore East, or carving a Halloween pumpkin, he poured every ounce of himself into the task at hand.

“My brother was a triple Scorpio,” Gregg Allman told Classic Rock. “He was passionate and intense. Always the first to face the fire. If there wasn’t nothing happening, he would start something. Plus he had a heart of gold. He was a wonderful person, and very much alive.”

“Duane was like Goethe’s Faust,” added drummer Butch Trucks. “He wanted to experience everything life had to offer – good or bad, didn’t matter.”

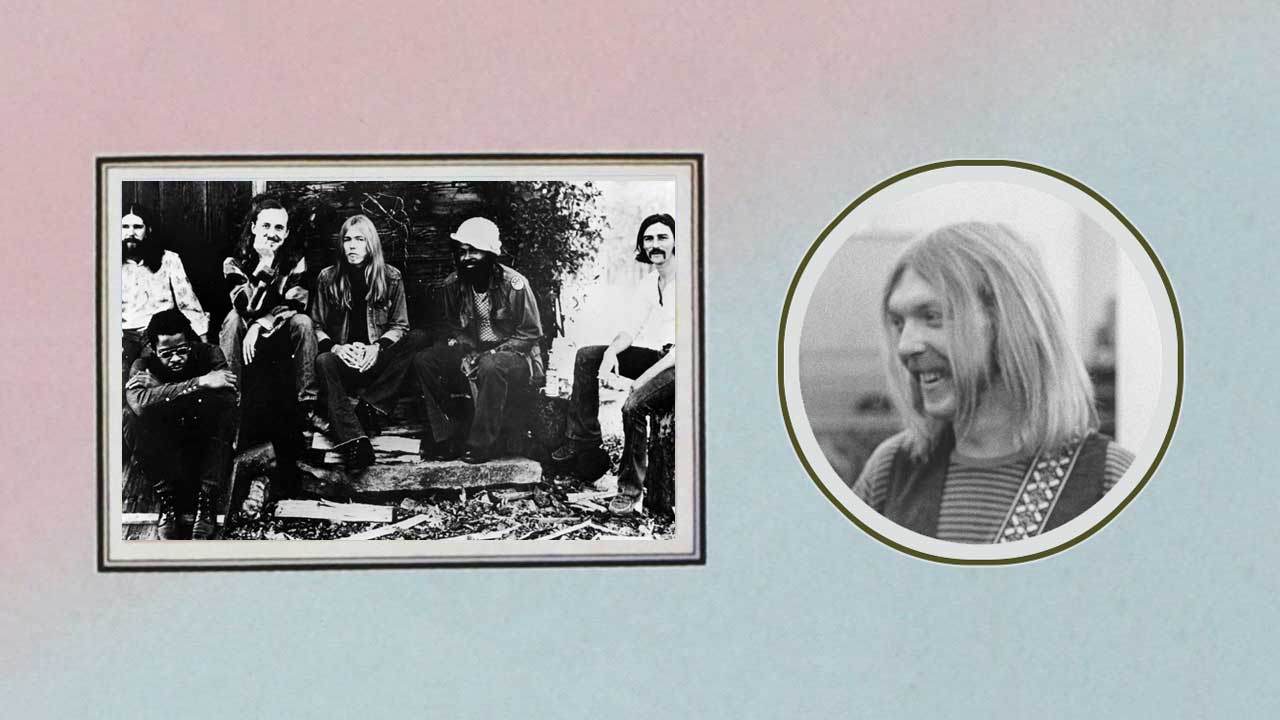

It was Duane’s energy and zest for life that, in two short years, had helped drive The Allman Brothers Band to become one of the hottest acts in America. By autumn 1971 even the old folks in Macon knew that these hippie boys living in their midst were something special. Their latest album was in the Top 10 and had just earned them their first gold record.

“It took a while but they started warming up to us,” Gregg said with a laugh. “When we first hit town some people were kind of in awe because of the way we looked. Other people thought we were a bunch of hoodlums. There was a girls’ college, Wesleyan, on the outskirts of town and they told them there: ‘Don’t go near those Allman boys!’”

Not that the local girls would have had much opportunity to get in trouble.

“We got to working so hard on the road, that we’d just come home to sleep,” Gregg said. “In 1970 I think we worked 306 nights out of the year.”

All that touring had paid off. At Fillmore East, the album that was riding high in the US chart, captured a band positively on fire with what brother Duane liked to call their “religion”. The tenets of it involved a deep-fried baptism in blues, rock and jazz, coupled with a faith in your fellow bandmates and the ability to testify with your instrument of choice.

With Duane’s bluesy slide guitar parrying with Dickey Betts’s melodic guitar lines, dual drummers Butch Trucks and Jaimoe Johanson pounding out complex counter-rhythms, and bassist Berry Oakley and little brother Gregg Allman muscling through it all with his Hammond organ licks and moonshine soul voice, the Allman Brothers Band made telepathic connections beyond most bands’ wildest dreams, elevating their lengthy jams to transcendental experiences.

That new level of confidence was evident in the three songs the band had already cut for their next record. But, as of mid-October, the record making and touring were on hold. It was time for a much deserved break. With three weeks off, the guys hung out at favourite Macon spots Grant’s Lounge and the H&H Restaurant, but mostly they just kicked back at the big house, drinking beer and smoking weed.

On October 28, Duane returned from a trip to New York that included a few days of rehab to wean himself off a recently acquired heroin addiction (he hated needles, so he’d been snorting the smack). Upon his arrival he was his usual enthusiastic self, stoked about the success of the At Fillmore East record and talking a mile a minute about the band’s future. He told their roadie, Red Dog: “We got it made now. We’re on our way. Ain’t gonna be no more beans for breakfast.” By nightfall of the following day Duane was dead, leaving the band shattered and in disarray.

This is the story of how they picked up the pieces and finished the record they’d been working on: Eat A Peach, the eventual double album that acted as a benediction and a bridge to the future, a testament to the strength of five friends to overcome tragedy and make some of the best music of their lives.

It was about 5:30 when Duane left the big house on that fateful day. He hopped on his motorcycle and led a small caravan of two cars – Berry Oakley in one, Duane’s girlfriend Dixie and Berry’s sister Candace in the other – to pick up gifts for a surprise birthday party that evening for Berry’s wife Linda.

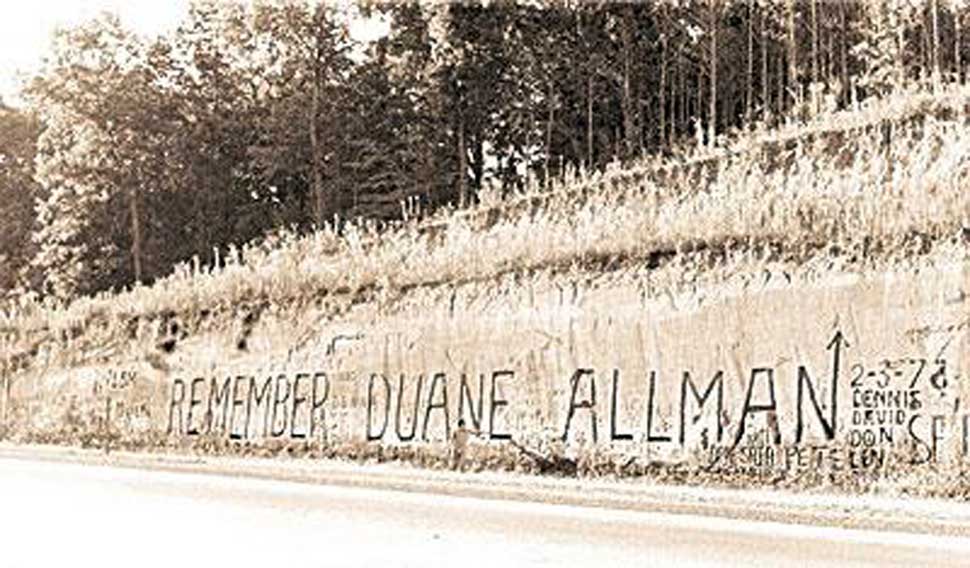

As usual, Duane was riding his Harley-Davidson Sportster much too fast. As he sped towards the intersection of Hillcrest and Bartlett, a flatbed truck with a lumber crane emerged ahead of him. Duane tried to swerve around it, but when the truck stopped suddenly he hit the ball of the crane and was thrown from his bike. The Harley bounced into the air, landed on Duane then skidded another 90 feet, pinning him underneath.

When Dixie and Candace reached him, Duane was conscious, with just a few scratches on him. He was rushed to hospital, but after several hours of emergency surgery he died from massive internal injuries. He was a three weeks shy of his 25th birthday.

“I walked out of the hospital stunned,” remembered Trucks. “You simply cannot absorb something that overwhelming all at once. It took a couple of weeks before I could even accept that he was dead. I mean, I still have dreams, 40 years later, that I run into Duane. I’ll be out somewhere and I just run into him. There’s still part of me that hasn’t turned him loose, and never will.”

Gregg called it: “a nightmare I can’t exactly remember”.

Duane was buried with a Coricidin medicine bottle – his slide of choice – slipped on his finger and a joint in his pocket. His funeral was attended by musical friends like Dr John, Delaney Bramlett and Roger Hawkins. After his fellow bandmates played a few songs in tribute, including Statesboro Blues, Atlantic Records producer Jerry Wexler delivered a grief-choked eulogy. He concluded by saying: “This young, beautiful man who we love so dearly, but who is not lost to us, because we have his music – and the music is imperishable.”

In the days following, however, the question remained: was The Allman Brothers Band also imperishable?

“At the time, we were going to take six months off before we decided anything,” Trucks said. “After a week, we all started going crazy. For a musician there’s only one way to get shit out of your system and that’s play music. We realised we had no choice but to go on.”

Drummer Jaimoe Johanson agreed: “There wasn’t any doubt. That’s what Duane would’ve wanted us to do, keep going. It’s weird, though, because Duane always said: ‘I’ll be the first one to go.’”

Gregg recalled: “We had a long meeting after everybody got their brains back. I said that if we didn’t keep playing and recording and travelling, we were going to fall by the wayside and we’d never amount to much at all. I didn’t want to sound like a fortune teller, but that’s how I saw it. So we got back out on the road and did a short tour, then went back into the studio."

When the band played at Auburn University, Duane’s friend Steve Foster was there. Foster played keyboards in Moody’s Goose, a band that would open several dates for the Allmans on the Eat A Peach tour.

“It was a stunning show, one of the first times they’d ever played without a second guitarist,” Foster recalled. “Whenever they came to Duane’s leads, Dickey just played rhythm. And suddenly the crowd started singing Duane’s leads. There were at least 10,000 people there. Everybody around me was crying. It was amazing, an almost religious experience.”

Though Betts would step up as a fine slide player and lead guitarist, he has admitted that it was a difficult period.

“I used to have a recurring nightmare,” he said. “In it, the band is on the road, and we end up on a show with Delaney & Bonnie, Duane’s old touring buddies. We see Duane at the show, and he says: ‘Hey, man, how’ve you been?’ And we say: ‘Great.’ And then we all get together and play, and everything’s all right again. That dream probably kept me sane. Until I could realise what happened. That was about three years later.”

On November 25 The Allman Brothers played two shows at New York’s Carnegie Hall. That day, the latest issue of Rolling Stone hit the newsstands. In it was an obituary of Duane, along with a feature on the band that had been written a month before his death. The obit, by future Bruce Springsteen manager Jon Landau, was respectful.

The feature was another matter. Written by Grover Lewis as a candid account of a week on the road with The Allman Brothers Band, it was a hatchet job. When quoting the band, he resorted to Deliverance-style dialect: ‘pretty’ became ‘purdy’, ‘guitar’ became ‘git-tar’. Worse, he painted them as coke-addled, comic book-reading prima donnas. The article infuriated the band, and mentions of Rolling Stone still rankled. “About a tenth of what they print is accurate,” was Gregg’s assessment.

After the New York shows, the band rolled southward towards Florida. As always, they travelled in their trusted Winnebago motor home, affectionately known as Winnie.

“The music collection in there was just incredible,” Gregg recalled. “We listened to The Father And The Son And The Holy Ghost by John Coltrane – free jazz, everybody in the band just blowing, just crazy. Everything from that to Miles Davis to Jimmy Smith to Taj Mahal.”

Jaimoe said: “Dickey was into Chuck Berry. Butch was into Grateful Dead and Dylan. Berry was into blues and jazz. And I was the jazzer. When we had the Winnebago, hell, all we played was The Tony Williams Lifetime and Rahsaan Roland Kirk. Eat A Peach tracks like Mountain Jam and Les Brers In A Minor were our versions of free jazz. I guess it was more on a level that was understandable to people than what Coltrane was doing. But we were disciples of all that stuff.”

B y mid-December, they’d parked ol’ Winnie at Miami’s Criteria Studio and got down to business finishing the new album with producer Tom Dowd.

“Tom would come into the studio and he would listen to the whole band,” said Jaimoe, “then he’d walk around to each individual, listening to only that person for a few minutes. When he went back into the control room he did the most natural thing a producer can do: he captured the sound he heard in the room on tape; he didn’t turn knobs and try to change the sound. It makes so much sense, but it’s rare to find a producer who understands how to do that.”

“He became quite a father figure,” Gregg said. “At the same time, a friend and an equal. He really cared about every note that went down. He loved us, loved the music. He wouldn’t ever say: ‘Why don’t you try this?’ If an arrangement wasn’t gelling, he might make a suggestion. He was there just to help us create our records.”

First down on tape was Gregg’s Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More, a gospel-flavoured rocker whose optimistic lyrics flew in the face of tragedy.

“That song helped me get back on my feet after Duane passed,” Gregg admitted. “I remember it just kind of flowed right out of me. It didn’t take more than a couple of days to finish it. Some songs are like that, they just ooze right out. Other ones you got to chase around the piano for a year and it’s just kind of a battle.”

The second new song, Melissa, was, if not a battle, awaiting game.

“I wrote that back in ’67, two years before the band got together,” Gregg recalled. “I was on the road, playing clubs and I was really lonely. I had a girlfriend back in Daytona Beach, but we had broken up. So I wrote this song about somebody that I wished I’d had with me. But I couldn’t figure out a name for it. ‘Back home, they’ll always run to Sweet… Barbara? No. Sweet… Ethel?…’ I was stuck.

"Then one night I was in the grocery store getting some coffee. There was this Spanish-looking lady, and she had a toddler with her, and the kid was running up and down the aisles. When she got out of sight, the lady yelled: ‘Oh, Melissa. Come back!’ I heard that and I could’ve gone and kissed that lady. ‘Melissa. That’s it!’”

Duane had loved the song, probably because he recognised himself in it.

“When I first showed it to him he was kind of like: ‘Eh’.” Gregg laughed. “But then every time he got a little tipsy he’d say: ‘Little brother, grab your guitar and play that song about the gypsy.’ So I would. And it really grew on him, until it became his favourite song of mine.”

Those two, plus Betts’s nine-minute instrumental tour-de-force Les Brers In A Minor, were added to the three songs the band had already recorded with Duane – Blue Sky, Stand Back and Little Martha.

Of the country-flavoured Blue Sky, Trucks said: “Dickey wrote that for his girlfriend, Sandy Bluesky. He was very insecure about the song. We had to almost beat him up to make him sing it. When you have Gregg Allman as lead vocalist, and you’re supposed to sing on the album, you can imagine his insecurity. When we first started playing the song it was much too heavy. We went at it with a sledgehammer [Betts wanted the song to sound “light and airy”].

"The one thing about Duane that made him such a genius as a recording guitar player is that he could see where a song needed to go. Duane picked up an acoustic guitar, and that changed the feel of the song, and gave it a swing that was missing.”

Duane stayed on acoustic guitar for his composition Little Martha. The instrumental came to him while he was asleep. Duane dreamed he was in a Holiday Inn motel room with his late friend Jimi Hendrix, and Hendrix was telling him about a new song. To demonstrate, Jimi walked over to the sink and used the tap as a fretboard. When Duane woke up, he grabbed his guitar and captured what he remembered from the dream. Ace guitarist Leo Kottke, who has covered Little Martha, calls it “the most perfect guitar song ever written”.

With six songs in the can, the band pondered the shape of the album. So soon after Duane’s death, it was unthinkable to release something that featured him on only three tracks. The solution was to go back to the mother lode of live recordings made at the Fillmore East. After listening to the tapes, they picked One Way Out, Trouble No More and their ultimate live showpiece, the 33-minute Mountain Jam, a song that Trucks called: “the apex of who we were as a band”. The only problem,” he says, “was there was only one decent recording of it good enough to put out, but it was also one of the worst we ever played. We said we had to put it out, because Duane was on it. But had Duane not died, Eat A Peach would have been just a single album.”

Mountain Jam demonstrates the band’s stunning on-stage interplay. They even had a phrase for it: Hittin’ the note. It was coined by bassist Berry Oakley as a kind of early-70s version of ‘in the zone’. He said: “When you’re really feeling at your best, that’s what you describe as your note.When you’re really able to put all of you into it and get that much out of it.”

Jaimoe: “The energy is the same, whether it’s a baseball team, a band, or a team of doctors. When you get more people thinking in terms of one, you get more accomplished. And the ideas can be as crazy and different as day and night, but when you have the ability to think as one, you get a hell of a lot of positive things done.”

At the end of Mountain Jam, Duane shouts: “Berry Oakley, Dickey Betts, Butch Trucks, Jai Johnny Johanson, Gregg Allman, and I’m Duane Allman. Thank you!” He couldn’t have known that when the recording appeared it would sound as the closing of a chapter on the band’s history.

The double album Eat A Peach (subtitled Dedicated To A Brother) was released in February 1971 to strong reviews. Charles Shaar Murray wrote in Oz: “The Allman Brothers Band keep right on hittin’ the note.” Rolling Stone tried to earn back the good graces of the band with a review that called them “the best goddamned band in the land” and the album “a simultaneous sorrowed ending and hopeful beginning”.

It was in the US chart by early March, and climbed to No4. As it turned out, Eat A Peach was a brief respite from more tragedy and trouble. Nearly a year to the day after Duane’s death, bassist Berry Oakley died in a motorcycle accident in Macon.

“I don’t think Berry really knew how to exist in a world without Duane,” Trucks said of Oakley’s decline. Later, drugs, drink, ego clashes, label problems and lawsuits would eventually break up the band not once but twice (when Betts was unable to curb his substance abuse, they fired him in 2000). Gregg Allman often reflected on what might have been had his brother lived.

“I’ve often wondered that. But something tells me we wouldn’t be together any more. Or we would have at least broke up two or three times, which we did anyway. That’s a hard question. Duane was so lightning, man. He might have gone off on his own. But then he dug his little brother’s singing, and he might’ve come back.”

“Success killed The Allman Brothers,” Trucks said. “Brothers And Sisters [the Allmans album released in 1973] was the death knell. We absolutely lost all sense of why we were doing this, and became rock stars. Had Duane lived, I think he was wise enough to understand what was going on, and if he’d have seen us acting like the fool idiots that we were he would’ve kicked our butts, or he would have left and did something else.”

In 2006, as The Allman Brothers Band geared up to play a round of full-album shows to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Eat A Peach, the surviving members commented on its enduring appeal.

Jaimoe: “It knocks me out. I understand why people are so moved by it. If I’m moved like the way I’m moved by John Coltrane or Miles Davis, we’re talking about personal expression, about the way you feel about something.”

Trucks said: “We took it to where Cream and the Grateful Dead took it, then added John Coltrane and Herbie Hancock to the mix and stirred it a bit, and we were up in places that no one else was thinking about. When I hear people describe Eat A Peach as southern rock I get fighting mad.”

Gregg concluded: “One of the hardest parts of doing a record is putting the songs in the right order: you want hills and valleys, and you don’t want the music to get mundane, and it will do that if you put the wrong two songs together. I think Eat A Peach has just the right sequence. I really love the album, and I’m so glad it did come out as a two-record set. That and Fillmore East are definitely the roots of our whole thing as a band.”

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 166, published in January 2012. Gregg Allman and Butch Trucks both died in 2017.