SIXTY ONE years ago, when he was nine years old, Ray Bradbury stopped clipping out the daily Buck Rogers space strip from the Waukegan News-Sun. The decision was to be the turning-point of his life.

He was mad about the strip. But his friends in fourth grade made fun of him. Buck Rogers wasn't important, the future wasn't going to happen. So he tore up his entire collection.

One morning about two weeks later he woke up crying. "I asked myself: 'Why am I crying, who died?' The answer was me. I asked: 'Why am I dying, what am I dying of?' The answer that came was that I was dying because I had destroyed the future because I had listened to those fools.

"Then I said: 'Well, what's the solution, how can I not die?' And the answer was, go back and collect comic strips and Buck Rogers and make your life whole. So I went back and started collecting again. All of a sudden all of my life came back, all of my love.

"And then I made up my mind that I would never listen to another damn fool ever in my life. That was the day I learned that I was right and everybody else was wrong. If God treats you well by teaching you a disastrous lesson, you never forget it."

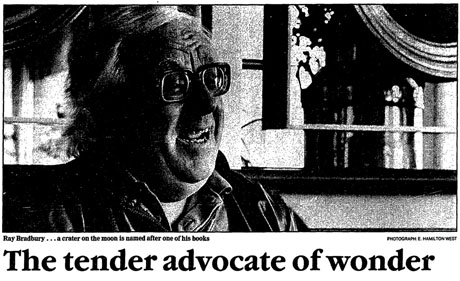

That is how Ray Bradbury managed to keep alive his sense of the miraculousness of life: "all my love" as he puts it. The rest, apart from an equally lonely testing time in his twenties, is literary history. This week he celebrated his 70th birthday in London as one of the 20th century's two or three best science fiction writers and certainly its most loved.

His 50-year output has taken the genre far beyond the simplicities of Buck Rogers. He is its delicate fabulist, its folk poet, its dreamer, its advocate of wonder. Most of all he brought tenderness and a gossamer-fine, gossamer-gentle imagination to a new branch of fiction which in his youth was largely the preserve of bug-eyed monsters. He has been rewarded in the coin he values most. Dandelion Crater on the moon is named after one of his books. In June, when he and Isaac Asimov were introduced to Gorbachev in Washington, the Soviet leader said: "We have known each other for quite some time. You are my daughter's favourite authors."

Last month a statue was unveiled to him in Waukegan, a suburb of Chicago. But the best compliment was probably one of the first. In the early 1950s when he met two of his prime heroes, Aldous Huxley and Christopher Isherwood, Huxley said to him: "You know what you are, don't you? You're a poet."

Bradbury, now a seraphically plump, silver-haired father of four and grandfather of seven, is here for yesterday's publication of his new novel A Graveyard For Lunatics, a detective story set in a haunted Hollywood studio. He goes easier on the adjectives than he used to but has the same old knack for a phrase. His stories began to burst upon the world of small magazines in the 1940s, and in one of the earliest he wrote: "Poverty made a sound like a wet cough in the shadows of the room."

In the new book he becomes the first writer I know to catch the atmosphere of one of those antique subterranean grotto-like gents' public lavatories "with the sound of secret waters running, and a scuttling sound like crayfish backing swiftly off if you touched and started to open the door."

Between these two titles came a flow of classics in and beyond the genre: The Martian Chronicles, The Illustrated Man, The Golden Apples Of The Sun, Fahrenheit 451, Dandelion Wine, The Day It Rained Forever, The October Country, Something Wicked This Way Comes. Bradbury's Martians, an aesthetic, fugitive race under the harrow of American settlement, might almost have been devised to fit an image in T. S. Eliot of an 'infinitely gentle, infinitely suffering thing'.

By the late 1950s a number of solicitous fans were starting to worry whether Ray Bradbury wasn't a little too sensitive for his own good. There is in his early stories an almost unbearable empathy with loss, loneliness and nostalgia. Those qualities were there in his upbringing and character. But so as you only realise when you meet him was a toughness that got him through.

His father was a power and light company worker, his mother a film buff who took him to Lon Chaney's Hunchback Of Notre Dame when he was three years old. That year, he remembers, "I started crying at the beauty of things." He also began to be allowed up for the family's Fourth of July celebration. His clearest memory of this is as a child of five.

"All of my relatives, three families, would come over to my grandparents' house and perch on the porch and we'd fire off $100 worth of fireworks in a single evening: $1,000 in today's money. At the end my grandfather would take me out to the end of the lawn at midnight. We'd light a little cup of shavings and put it underneath a Japanese fire balloon. We'd stand there waiting for the balloon to fill with warm air. Then we'd let it drift up into the night. I would stand there with my grandfather and cry because it was so beautiful. It was all over and it was going away. My grandfather died the next year and in a way he was a fire balloon going away."

School bored him and his parents weren't pushy. He left, determined to make his way as a writer but with little except images of fire balloons and Buck Rogers to support him. For ten years he spent four days a week reading literature in libraries; every week he wrote a story.

"You pay a certain penalty for going your own way. A lot of people think you're nuts and you're not as popular with girls as you should be. I used to take my short stories to girls' homes and read them to them. Can you imagine the reaction reading a short story to a girl instead of pawing her? I hated parties because I didn't dance. I'd go to parties, find a typewriter and write a short story while they were busy wasting their time.

"And I was effusive, I was raving about all sorts of things that people didn't understand. The answer I found is you stay away from the people who make fun of you and you join these ad hoc groups who understand your craziness. These are the people who took us to the moon. When you go to Cape Canaveral or any of the aerospace companies in California during the last 40 years, they're populated with these crazies who I grew up with.

"I felt a bit bookish, cut off from life. Then when I was 26 I met my wife. She was a bookshop clerk. She has been my lifeline. The day we married I handed five dollars to the minister and he handed it back to me. He said: 'You're a writer, aren't you? You're going to need this.'

"I have spent my life going from mania to mania. Somehow it has all paid off. But when I was 30 I used to go to parties in New York. I'd meet a lot of surgeons, doctors and ballet dancers. They were my contemporaries. They were all established in life by then.

"And they'd all say: 'Oh here comes Buck Rogers, here's Flash Gordon.' One night I said to this ballet dancer: 'Give me your phone number.' He said: 'Why?' I said: 'The night we land on the moon I'm going to call you.' So I took a lot of phone numbers. The week after we landed on the moon, I made a few calls. I just laughed at them and hung up."