Jan. 5, 2024, marked 336 years since the passing of an extraordinary woman you have probably never heard of: Catarina de San Juan.

Her life reads like an epic. Born in South Asia during the early 17th century, she was captured by the Portuguese at age 8 and sold to Spaniards in the Philippines. Spanish merchants then traded her across the Pacific to Mexico, where she became a free woman and a spiritual icon, famous in the city of Puebla for her devotion to Catholicism. As a scholar of colonial Latin America, I believe she deserves to become a household name for anyone with even a passing interest in Asian American history or the history of slavery.

Catarina was one of the first Asians in the Americas – a focus of my historical research – and arrived through a little-known slave trade that crossed the Pacific Ocean. In colonial Mexico, she lived in the “nideaquínideallá,” the “neither-from-here-nor-from-there”: a valley between acceptance and foreignness, an in-between state familiar to many migrants today.

The Life of Catarina

The particulars of Catarina’s journey are quite unfamiliar, even for those who study the history of slavery.

Most people have heard of the transatlantic slave trade, which lasted from the early 16th century to the mid- to late 19th century. It was responsible for the violent displacement of some 12.5 million Africans to the Americas.

The transpacific slave trade, on the other hand, remains largely unknown. From the late 16th to early 18th centuries, Spaniards forced some 8,000-10,000 captives onto rickety galleons, where they would endure a six-month odyssey from the Philippines to Mexico. The enslaved captives came from South, Southeast and East Asia, as well as East Africa.

After her capture, Catarina – whose name at birth was Mirra – was taken to Kochi, India, where she was baptized and received her Christian name. Later, in Manila, a young Spaniard stabbed and beat her within an inch of her life when she refused his advances. In her words, “Only the divine majesty knows what I went through.”

She only ended up on a galleon destined for Mexico because Captain Miguel de Sosa desired the service of a “chinita,” or little Asian girl. Yet he quickly realized that Catarina had uncommon virtues when she showed little regard for money or objects of material value. Sosa freed Catarina in his will.

For the next six decades, she led a life of social isolation, abstinence, humility and rejection of material pleasures – what her admirers saw as an exemplary life of holy Catholic suffering. She lived entirely on charitable offerings and, according to one Jesuit observer, wore only a “dark, wool dress” with “the crudest, the coarsest” cloak. Her modest lodgings were “filled with filthy critters.”

And she prayed. She prayed for water in drought, for Indigenous people dying of famine and disease, for ships lost at sea, for travelers braving the roads. She prayed for those who needed help the most.

Even as Catarina gained renown, some Spaniards questioned the sincerity of her devotion. Throughout Catarina’s life, detractors described her as a “trickster,” “a witch,” “untamed” and “unknowable,” while Spanish allies viewed her as evidence that all the world could be converted to Catholicism.

The Catholic priest who regularly heard her confessions was a Jesuit named Alonso Ramos. After Catarina died, he authored an enormous three-volume biography of her life, the longest text ever published in colonial Mexico.

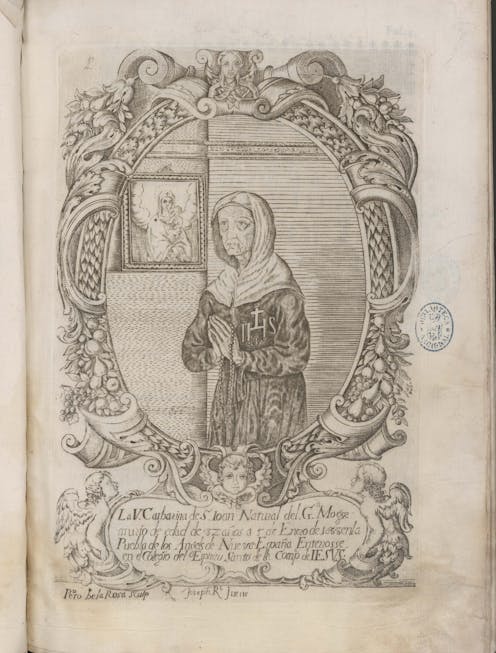

Ramos turned an unlikely subject – a formerly enslaved South Asian woman – into a superhero of the colonial world. Catarina’s portrait, which appeared in Ramos’ first volume, became a popular relic, and followers in Puebla converted her humble bedroom into an altar where Catholics could pray for her divine favor.

Historical amnesia

Why, then, do few people know about Catarina today?

The answer is twofold. First, Ramos’ text was considered controversial outside of Puebla because it depicted Catarina with powers reserved only for God, Jesus and the Holy Spirit. He describes her announcing prophecies, performing miracles, traveling in her dreams and regularly conversing with Jesus, whom she considered her celestial husband.

In short, Ramos had committed blasphemy. The Inquisitions of Spain and Mexico censored and burned his volumes shortly after publication. Inquisitors ended all devotion to Catarina’s image and took down the makeshift altar in her room.

Over time, the memory of the real Catarina morphed into something entirely different. Spaniards sometimes called her a “china,” the word colonists in Mexico used to refer to any Asian subject. Today, though, the phrase “china poblana” – the Asian woman from Puebla – refers to a popular, coquettish style of Mexican dress, with a patterned skirt, white blouse and shawl.

Virtually nothing about Catarina’s life has been preserved in the modern “china poblana,” which was invented in the 19th century. In fact, it connotes sexual confidence and national pride, two concepts that Catarina would have likely rejected.

Second, the field of Asian American history has been hesitant to peer south of the U.S. border, despite several noteworthy efforts. Many people in the U.S. remain unaware that many Asian people live in Latin America and the Caribbean – indeed, that they have lived there for centuries longer than in the United States. Asians had been coming and going from the Americas for over 200 years by the time the U.S. Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776.

Today, significant Asian populations inhabit nearly all Latin American and Caribbean nations, mostly due to later waves of immigration and indentured servitude. Brazil hosts the largest number of Japanese and Japanese descendants outside of Japan at around 2 million, and the Chinatown in Havana, Cuba, was once the largest in the Americas. Indo-Caribbean people are the first- or second-largest group on many Caribbean islands, including Trinidad and Tobago and Grenada.

Catarina de San Juan and the first Asians in the Americas challenge the traditional timeline and geography of Asian American history. Their stories also capture what many people who end up in the Americas have faced: the trauma of displacement.

As Catarina coped with the harsh realities of her new life, she once told Ramos that she frequently saw her parents in her spiritual visions. Sometimes, they were in purgatory, where Catholics believe their souls are purified before they can enter heaven. However, she most often envisioned them coming “in the company of the ship from the Philippines to the port of Acapulco, from where, on their knees, they came into my presence.”

Her pain and longing for a stolen family, a lost youth and a hazily remembered homeland were those of generations of Asian captives taken to the Americas. I believe that her extraordinary life merits long-overdue recognition.

Diego Javier Luis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.