There are certain summers when the energy of a whole generation seems to come to a head. It happened in 1967, when 75,000 young people descended on San Francisco for the first Summer of Love in search of psychedelic rock, mind-expanding substances and a different world to the corrupt and venal one they’d inherited. It happened again in 1988, as British ravers rode the wave of ecstasy and acid house that became known as the Second Summer of Love. As live music and festivals return after the last summer of isolation – and given that many of us haven’t cut our hair in a year – is it too much to hope that 2021 could herald a return to that sense of hippie idealism and utopian hedonism?

If anyone knows what it takes to spark a Summer of Love, it’s Carolyn Garcia. As an 18-year-old in 1964, she was recruited into One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest author Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, the technicolour troupe who paved the way for the Summer of Love by touring America in a psychedelic school bus handing out LSD like sacrament. Known as “Mountain Girl”, because she lived in the woods and rode a motorcycle, Garcia had a child named Sunshine with Kesey and was immortalised in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test before shacking up with (and eventually marrying) another icon of the era: Jerry Garcia, the shaggy-haired ringleader of The Grateful Dead.

Garcia, now 75, has remained true to the free-spirited ideals of her youth. Down the line from her home in Oregon, she remarks on how pleased she is that the state has recently legalised the use of psychedelics. “I just had my tiny microdose of psilocybin this morning,” she says breezily. “It makes me a little bit loquacious.”

She is not in the least bit surprised to receive my call. Garcia says she understood, even while it was still happening, that the ripples sent out from San Francisco in 1967 would be felt for decades to come. “We knew it was earth-shattering,” she says without hesitation. “Absolutely.”

Her first memories, however, aren’t about peace, togetherness and unity. They’re about how overwhelming it was to witness the endless streams of young people who began arriving in San Francisco’s ill-prepared Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood in 1966, lured by the siren song of free concerts, plentiful drugs and a licentious way of living. “It seemed like a thousand people a day were showing up, and they all needed a place to stay,” she remembers. “Most of them had hitch-hiked with nothing besides the grand scheme of getting to San Francisco for the summer. They were sleeping in the park, on people’s porches, under people’s porches. There was a lack of bathrooms. A lack of water. It became an issue of health and safety.”

Garcia was living in the Grateful Dead house on Ashbury Street at the time, and worked with groups like the radical street theatre activists The Diggers to open homes and find places to stay for the floods of flower children who kept pouring into the city. By 1967, she recalls, things had become a little more organised – and that January more than 20,000 people attended the Human Be-In, a seismic free event in Golden Gate Park held to protest a new law banning LSD in California. Underground chemist Owsley Stanley cooked up huge amounts of his White Lightning acid to mark the occasion, which brought together left-wing Berkeley radicals and anti-Vietnam War activists along with the Haight-Ashbury hippies in their rejection of mainstream American society. Psychologist and countercultural icon Timothy Leary was among the speakers, and he captured the rebellious mood with his newly minted mantra: “Turn on, tune in, drop out.”

For Garcia, who had seen first-hand how out of control crowds of young people could get, the most meaningful contribution came from the beat poet Allen Ginsberg, one of the godfathers of the scene. “Ginsberg was such a gentle cat,” she says. “He did a sort of clean-up mantra at the end of the Be-In exhorting people to be mindful, and got them to pick up all the trash. I think that was the first time anybody had considered the footprint that a large gathering leaves. People picked up after themselves and left it clean. That got a lot of attention.”

All that LSD washing around the streets of San Francisco wasn’t just opening people’s minds to the importance of not leaving the world looking like Glastonbury on the Monday morning after the festival. It was totally reshaping the city’s music scene. Joel Selvin, who dropped out of high school in Berkeley in 1967 before becoming the long-time music critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, remembers seeing bands like The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Big Brother and the Holding Company (fronted by Janis Joplin) turn their shows into improvised psychedelic rock jams that lasted as long as their trips did.

As the sound changed, so did attitudes. An active effort was made to break down barriers between audience and performers. “The music was the place where it all came together, and of course that was the part that really travelled well,” says Selvin. “It went out of the ballrooms of San Francisco and started to spread as the spear tip of this movement. It really was the soundtrack of a new community.”

While the original Haight-Ashbury scene was built around a rejection of capitalism, when that many young people gather in one place, someone is bound to try and figure out how to make a dollar from each of them. Selvin notes the air of cynicism that surrounded Scott McKenzie’s “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)”, released that May and written specifically by John Phillips of The Mamas & the Papas to advertise his own festival. “Phillips was not a hippie,” says Selvin. “He had made a lot of dough and was living in Bel Air driving a Rolls Royce, all that kind of anti-hippie stuff. That song was a Top 40 portrait of what somebody thought the San Francisco thing was about. It endures to this day because of the craftsmanship of the pop songwriting, but it doesn’t have one iota of San Francisco in it. It’s pure LA.”

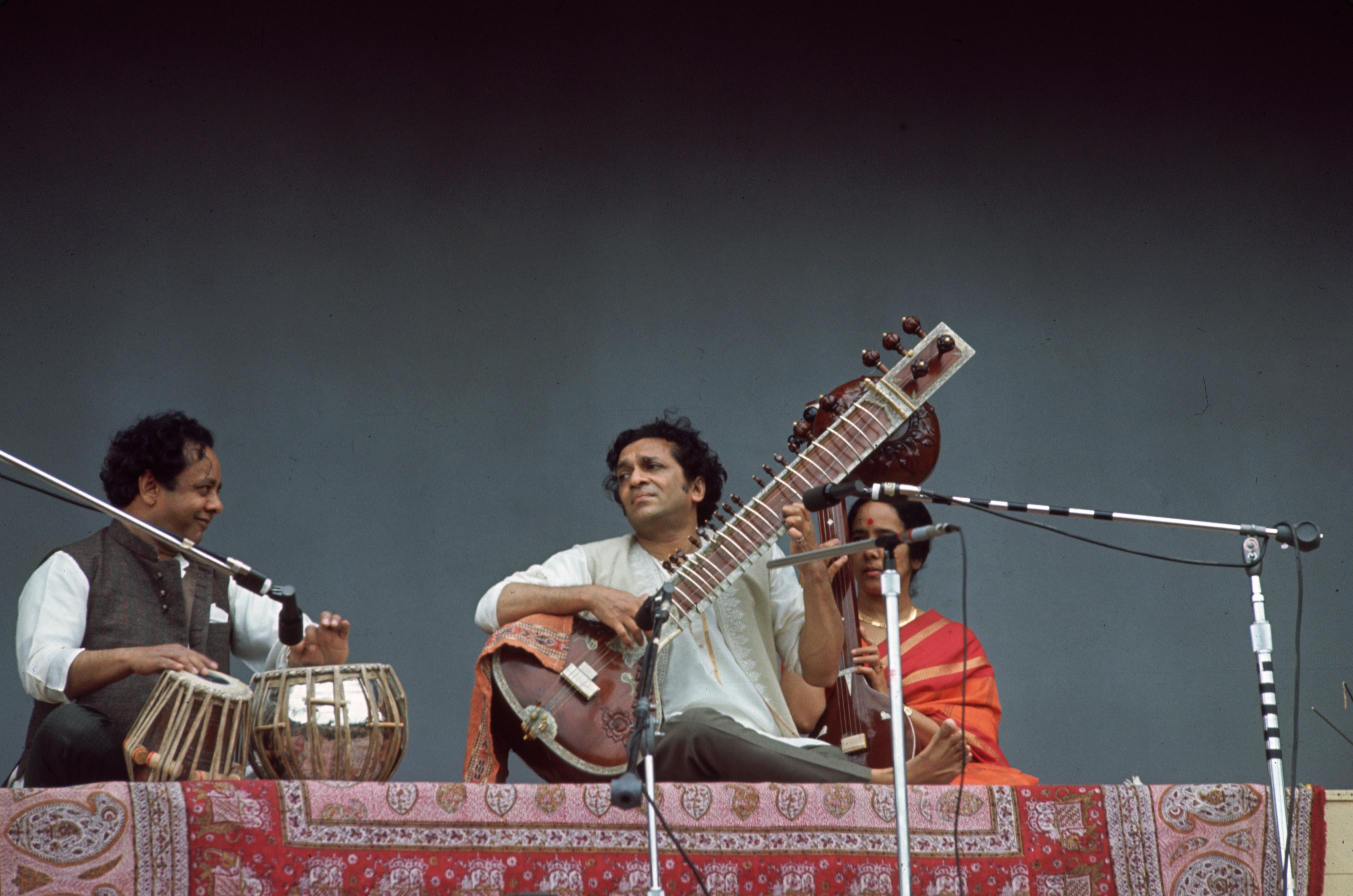

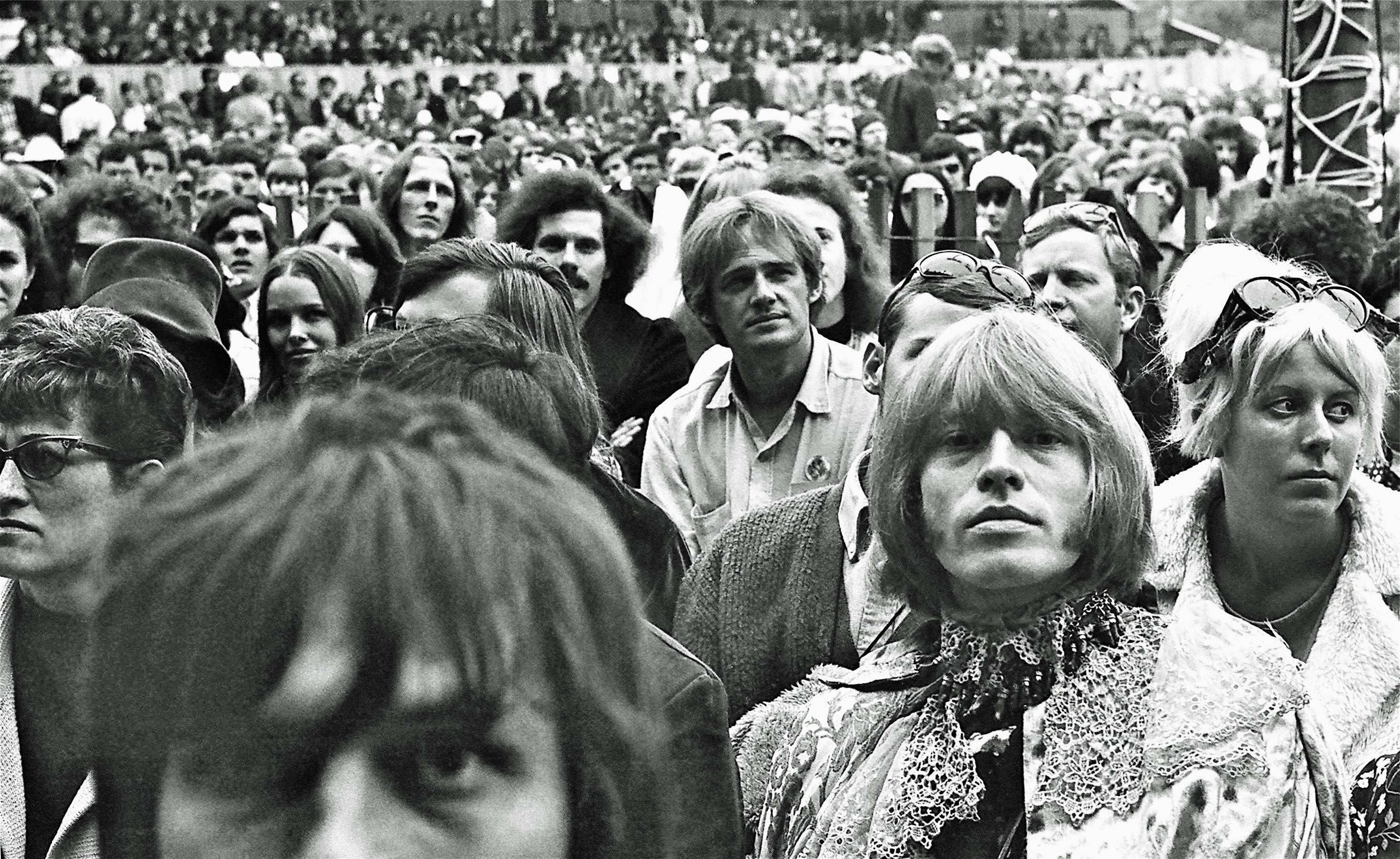

While Phillips and his manager Lou Adler may have been considered outsiders by the Haight-Ashbury scene, the festival they organised would become the Summer of Love’s crowning weekend: the Monterey Pop Festival. During three days of sublime sunshine in June that year, 90,000 ridiculously lucky people took in a hard-to-beat line-up that included The Mamas & the Papas, Otis Redding, Simon & Garfunkel, The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and the first major American shows by Jimi Hendrix, The Who and The Beatles’ favourite sitar maestro Ravi Shankar.

After some convincing, Haight-Ashbury favourites The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Big Brother and the Holding Company all played too. Garcia remembers the festival as a “wonderful, wonderful event”, although she hasn’t forgotten The Dead’s unhappiness at being sandwiched between The Who and Jimi Hendrix on the line-up. “That seemed unfair, because Jimi tore the place up,” she remembers. “Pete Townshend smashed his guitar, and then 45 minutes later, Jimi’s guitar was on fire. Jerry was really upset. Damaging an electric guitar was beyond our paygrade, but Jimi never saw any boundaries.”

By the time Hendrix’s Stratocaster went up in flames, a movement which had begun as a druggy, Dionysian, anti-materialist underground subculture in Haight-Ashbury had the attention of the whole planet. “The Human Be-In was not the beginning, but it was the great door opening,” says Garcia. “By that time, every newspaper in the world had gotten hold of these stories about the overrunning of San Francisco and people perked up and listened. It had a huge effect.”

Twenty-one years later, stood in the DJ booth looking out over the Haçienda nightclub in Manchester, Graeme Park experienced that same feeling of witnessing the start of an epochal shift. “It was just getting bigger and bigger,” he says. “We knew it was going to run and run.”

Park had been playing acid house records in his DJ sets at the Garage in Nottingham since 1986, and in February 1988 he and fellow DJ Mike Pickering hosted a night at the Haçienda intended to showcase the new sound they’d fallen in love with. A couple of months later, Pickering asked Park to cover for him at the Haçienda for three weeks – but insisted he first come back to Manchester for a night to experience how the scene was changing.

“I didn’t understand why, because we played similar music,” remembers Park. “But he said if I didn’t come up he wouldn’t let me do it. When I arrived it was madness. The last time I’d been up there everyone looked like they’d walked out of the pages of i-D magazine: MA-1 flight jackets, Levi’s 501s, white socks and Dr Martens. This time I walked in and everyone was wearing bright neon colours, baggy clothes, dungarees and bandanas. The Smiley logo was everywhere, and everyone had this wild look in their eyes. I went up to the DJ box door and Mike had the same wild look on his face. I said, ‘What’s going on?’ He took out a pill and said, ‘This is what’s going on.’”

Ecstasy played a similar role in the Second Summer of Love to the one LSD had played in the first: not just getting people high, but forging a euphoric sense of togetherness and community. That’s not to say absolutely everyone was off their faces. Gerald Simpson, better known as A Guy Called Gerald, produced one of that summer’s defining hits, “Voodoo Ray”, but says he personally preferred not to indulge. “I didn’t really do any of that,” he says. “I was just bang into the music. For me, the ‘acid’ in acid house meant stripped-down funk, or stripped-down disco. It was reduced to a groove that would create a trance-like feeling. I could get high just on that.”

While the first Summer of Love had largely centred around a small corner of San Francisco, the Second Summer of Love spread its tendrils across Britain in the form of club nights like Danny Rampling’s Shoom and Paul Oakenfold’s Spectrum and at warehouse raves, which were often illegal. “The north of England was full of derelict warehouses,” points out Park, “because the Thatcher government had come in and started to hammer the nails into the coffins of British industry.”

“Every week there was something new going on,” adds Simpson, who isn’t sure whether that sense of underground community could be replicated today. “Now we’re more of a global village,” he observes. “Before there were these little pockets where things could develop and then come out into the world maybe a few years later. Now as soon as something happens it trends or goes viral overnight and the energy is dispersed really fast.”

Park concurs. “I would love it if 2021 was another Summer of Love, but I’m not sure if it could happen again,” he says. “It feels more contrived now. The young generation are the social media generation. They’re on TikTok, they’re on Instagram, and they’re trying to do what everyone else is doing. It’s difficult to stand out if you’re trying to do something different or a bit weird.”

Perhaps he’s right, but maybe – just maybe – the conditions could yet be right for a new Summer of Love. Young people, stuck inside for so long, must be burning with a year’s worth of pent-up energy and desire. In the meantime they’ve become increasingly politically radicalised, particularly around the urgent need to protect the planet from being choked to death by greedy corporations – just as the hippies preached. Meanwhile, in both Britain and America, more research is being done right now into the obvious mental health benefits of psychedelic substances than at any time since the era of Kesey and Leary. Is it so hard to imagine a new generation choosing to turn on, tune in and drop out?

Back in Oregon, Garcia says she may have just the thing to light the spark. “We should have more Human Be-Ins,” she recommends. “At a time when people are constantly struggling with each other, it would just be so nice if they could figure out what seems simple now, but wasn’t really, and that’s that people really can get along – and they can have fun while they’re doing it. It sounds easy, but it doesn’t happen unless people really plan for it.”