On 1 September 1949, Carol Reed’s celebrated thriller The Third Man was released. It was an immediate hit and in the ensuing seven decades, The Third Man’s popularity has remained constant, with frequent appearances on TV and in the cinema, as well as a beautiful restoration in 2015.

The film has also featured regularly in lists of the greatest films of all time, and many critics treasure it. It’s been 20 years now since the BFI placed The Third Man at the top of their own list of greatest British films, so perhaps it’s time for a reappraisal of the finest examples of British cinema.

Here, to mark the 70th anniversary of The Third Man, is my top 20 greatest British films.

20. Local Hero (Bill Forsyth, 1983)

Eccentric Texan oil magnate Burt Lancaster despatches an underling to buy an entire Scottish coastal village so he can build a refinery, but his man is soon seduced by his new environment. Full of Ealingesque charm and whimsy, but as the stooshie over a certain golf course in Aberdeenshire has shown, remarkably prescient, Local Hero followed the director’s equally engaging Gregory’s Girl into movie fans’ hearts. Mark Knopfler’s winning score adds to the feel-good vibe of a movie that leaves you with a great big smile on your face.

19. Withnail and I (Bruce Robinson, 1987)

A British movie that inspired a student drinking game and has its many hilarious lines quoted verbatim by fans (“Don’t you threaten me with a dead fish!”, etc.) must have something going for it, and Withnail and I certainly does. Paul McGann and a marvellously wasted and acerbic Richard E Grant make the most of Robinson’s terrific semi-autobiographical script of two base, out of work actors who drown themselves in a diet of booze, pills and lighter fluid on a disastrous holiday in the country circa 1969. The whole movie is basically one long bender followed by the mother of all hangovers (“Look at my tongue, it’s wearing a yellow sock”) and stands as a perfect flip side of the so-called swinging Sixties.

18. The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957)

This celebrated prisoner of war epic is set in Japanese-occupied Burma with Alec Guinness as the British colonel obsessed with building the titular bridge. Colonel Nicholson’s reasoning is if his men can build the best bridge they can, it will lift their morale and show the brutal camp commandant that the British soldier is superior to the Japanese – but he is oblivious that in doing so, he may be aiding the enemy. As much a battle of wills as a great action movie, this perennial television favourite won seven Oscars including best film, best director for Lean and best actor for Guinness.

17. The Ladykillers (Alexander Mackendrick, 1955)

Criminal mastermind Alec Guinness rents a room in a sweet old lady’s house (a scene-stealing Katie Johnson) while he and his gang masquerade as musicians, plotting and executing a daring robbery. When the indomitable old lady learns the truth and threatens to reveal all to the police, the gang decide they have to do away with her. They then argue over who is going to do the dirty deed and only end up offing themselves in a series of gruesome but highly amusing vignettes. Scottish director Mackendrick was soon to depart for the USA to make the very dark, noirish Sweet Smell of Success and this peerless black comedy was his final film at Ealing and a fitting swansong for one of the studio’s finest talents.

16. A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971)

From the Anthony Burgess novel, Kubrick’s scathing satire set in a dystopian society in the not too distant future predictably caused controversy on release and has continued to do so through the subsequent decades, with one reviewer accusing Kubrick of making “intellectual pornography”. Disturbed by reports that the stylised violence in the film had provoked copycat crimes, Kubrick withdrew the film in Britain in 1973, and it wasn’t made available again until 2000, a year after his death. Even now, A Clockwork Orange still divides opinions, and as the recent revival demonstrated, in an era when audiences have long been conditioned to extreme violence on film, hasn’t lost the power to shock, while still raising as many questions as answers about morality, free will, and authority.

15. Get Carter (Mike Hodge, 1971)

The opening title sequence of Get Carter finds Michael Caine as Jack Carter on board the London to Newcastle train reading Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely. But Carter is no Philip Marlowe knight errant. He’s an ice-cold enforcer for a London crime mob returning home to Newcastle, hell-bent on finding out how his brother died. In doing so, amid a web of corruption, pornography and murder, the relentless Carter leaves a trail of bodies all around the northeast, but his own fate had already been sealed when he stepped aboard that train. Brutally realistic and reflecting the growing pessimism of the early 1970s, Get Carter was underappreciated on release and then grew into a cult film. Now, it is viewed as one of the most influential British crime thrillers ever.

14. Brief Encounter (David Lean, 1945)

Two happily married people meet by chance at a railway station and a short, intense, but doomed love affair ensues. Gloriously old fashioned romance from Noel Coward’s one-act play, full of classic British restraint and stiff upper lips. The cut-glass accents and some of the dialogue may grate nowadays but the poignancy of the story, the superb performances by Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard, the trains and the unforgettable use of Rachmaninoff’s second piano concerto make for an enduring classic.

13. Barry Lyndon (Stanley Kubrick, 1975)

Boasting sumptuous production values, this exquisitely mounted, leisurely paced adaption of William Makepeace Thackeray’s novel about the rise and fall of an 18th-century Irish rogue hero received middling reviews when first released but still won four Oscars, including not surprisingly, the costume, cinematography, and art direction categories; for Barry Lyndon is undoubtedly one of the most stunningly beautiful pictures ever made.

Kubrick shot all but a few scenes by natural light and candlelight, investing the film with the authentic look of the period and evoking the works of Gainsborough and Hogarth – exactly the look that Kubrick desired. Like other films in the Kubrick canon that originally bypassed the critics, Barry Lyndon is now recognised for its true worth. Invest three hours of your life in viewing it and you will not be disappointed.

12. Great Expectations (David Lean, 1946)

A wonderful achievement by Lean who managed to distil and transfer the long, intricately plotted novel from the page to the screen without losing any of the narrative flow. Featuring an exemplary cast, Oscar-winning cinematography and a number of unforgettable scenes such as the opening graveyard sequence, the first glimpse of Miss Havisham in her wedding dress, and the moonlit pursuit of Magwitch across the marshes, this is the Dickens adaption against which all others should be measured.

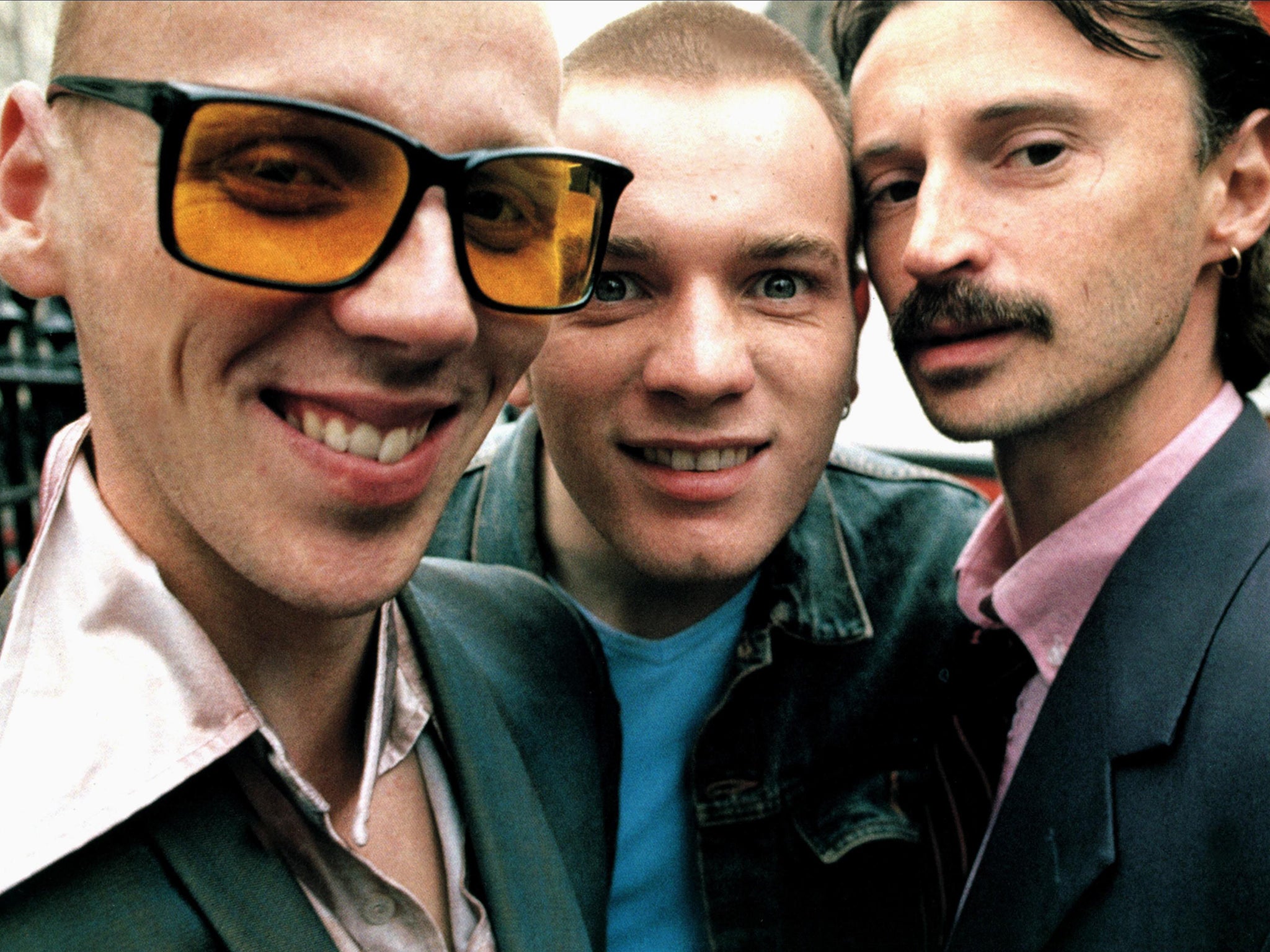

11. Trainspotting (Danny Boyle, 1996)

More than two decades on, Trainspotting’s rampage through Edinburgh’s heroin culture remains terrifying, shockingly funny, horrifying and heartbreaking in equal measure. In a uniformly brilliant cast, Ewan McGregor gives a career-defining performance as Renton, and Robert Carlyle’s Begbie is terrifyingly but compulsively watchable. Trainspotting was criticised in some quarters for glamorising drug-taking. It doesn’t – think of the scenes involving the minutiae of actually scoring and taking drugs as well as the harrowing cold turkey sequence, but Trainspotting does challenge audiences on the reasons why people do, whether we emphathise or not.

10. Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962)

Lawrence of Arabia shot Peter O’Toole to fame, but he had to fight the desert every inch of the way as the star of one of the most beautifully photographed films ever made, with David Lean stunningly sealing his status as one of the great visual directors. Think of the famous shot of Omar Sharif miles in the distance gradually coming into view through the haze of the desert sun, and the epic sweep of Freddie Young’s Oscar-winning cinematography throughout.

Winner of six other Oscars including best film, best director and for Maurice Jarre’s unforgettable score, Lawrence of Arabia is that rarest of beasts – an epic blockbuster that is also thoughtful and literate.

9. Monty Python’s Life of Brian (Terry Jones, 1979)

Praise be to George Harrison for putting up the money when EMI pulled out, thus ensuring that the Python’s satire on organised religion and blind faith saw the light of day. The fall out over the alleged blasphemy in the film couldn’t overshadow just how funny and on the money The Life of Brian was, and just made more and more people want to view it, making it even more successful than it would have been. The Python’s finest hour (and a half).

8. Kes (Ken Loach, 1969)

A beautifully filmed adaption of the Barry Hines novel A Kestral For a Knave with a remarkable performance from David Bradley as Billy Casper, a 15-year-old boy from a deprived background whose life is transformed when he finds a young falcon and trains it, in the process forming a close emotional bond with the bird. There’s comedy and tragedy in equal measure in Kes, with the hilarious football scene with Brian Glover as both referee and Bobby Charlton and the heartbreaking ending demonstrating Loach’s devastating gift for both. The cast of the mostly non-professional actors wasn’t told what to expect in many of the scenes, hence the real shock and pain on the boys’ faces when they were caned by the bullying headmaster. With Chris Menges’ superb camerawork lit only by natural light, Kes remains a true British classic and the peak of Loach’s illustrious body of work.

7. The 39 Steps (Alfred Hitchcock, 1935)

John Buchan’s famous novel has a rather anti-climactic ending and there are no female characters, so the director put his own personal stamp on it. The result is Hitchcock’s first true classic bursting with what would become the Master’s signature tropes – famous locations, the glacial blonde, the innocent man on the run and the (literally) memorable climax.

The 39 Steps also features one of the first examples of the director’s MacGuffin, his celebrated plot device (in this case military secrets being taken out of the country by agents of a foreign power) that, on the one hand, drives the film but on the other, has little relevance to the outcome. There isn’t a wasted moment in the entire film with a dream pairing in dashing Robert Donat and icily beautiful Madeleine Carroll.

6. Distant Voices, Still Lives (Terence Davies, 1988)

Distant Voices, Still Lives is a wonderful semi-autobiographical chronicle of a 1940s/50s working-class Liverpool family which received a 4k restoration last year, reminding us of the beauty and fine detail of the director’s art. Davies movingly and lyrically contrasts the hardships of everyday life living in the shadow of a brutal husband and father with the small pleasures and little victories – weddings, visits to the cinema and sing-songs down the pub. Pete Postlethwaite’s performance as the abusive head of the family is seared on the memory while Freda Dowie excels as his stoical wife, and Davies’s use of period music in the film is perfection.

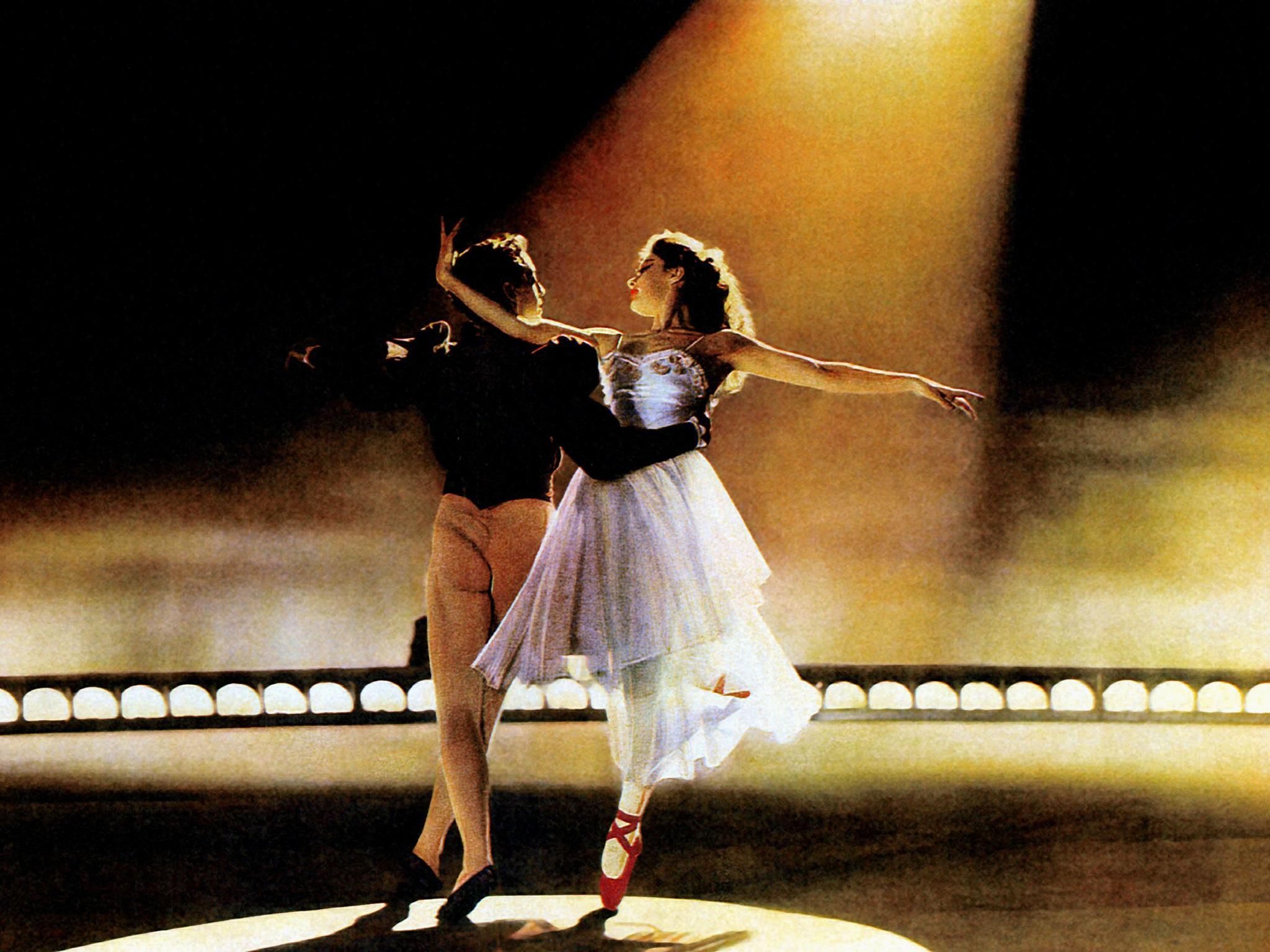

5. The Red Shoes (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1948)

The Red Shoes is even darker than the Hans Christian Anderson original, with a radiant Moira Shearer in her first film as the young ballerina torn by the conflicting demands of her Svengali-like dance master and her struggling composer lover. The wonderful score and stunning sets won Oscars but Jack Cardiff’s sumptuous technicolour cinematography somehow didn’t even get nominated. This is the perfect example of Powell and Pressburger’s unique vision and arguably the finest synthesis of dance, music and drama ever committed to film.

4. Don’t Look Now (Nicholas Roeg, 1973)

Rarely has a city been used so effectively in cinema than in Roeg’s adaption of the Daphne Du Maurier short story Don’t Look Now, which has grown in stature over the past four decades. Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland are superb as a grieving couple who go to Venice to try and forget the death by drowning of their daughter, only to experience disturbing reminders of their daughter. Both a Hitchcock influenced supernatural chiller and a highly emotional study of love and loss, Don’t Look Now exudes mystery and menace thanks to Roeg’s stunning use of Venetian locations as he masterfully and inexorably builds the suspense until the shocking climax.

3. Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1949)

Alec Guinness famously and brilliantly played eight different characters in this pitch-black comedy of manners, but he is matched all the way by a wonderfully urbane and detached Dennis Price as the serial killer who murders his way to a dukedom. The film mercilessly takes barbed shots at the aristocracy and class divide, and the talented but troubled Hamer directs with a sureness of touch that does full justice to the billboards declaring Kind Hearts “a hilarious study of the gentle art of murder”. Price’s gentle voiceover and the savage twist in the tale are the icing on the cake in a film with no room for sentiment or remorse, and which remains the high watermark in the Ealing canon.

2. A Matter of Life and Death (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1946)

Yet another unique film from Powell and Pressburger, this is a technically brilliant fantasy starring David Niven as a young pilot in the Second World War who cheats death just as he falls in love with radio operator Kim Hunter, and must stand trial in a heavenly court (or is the court in his own mind?) for his life on earth to continue. In a reversal of existing tropes, heaven was filmed in black and white and earth in glorious technicolour, and there are some stunning special effects that even now, impress. Ultimately the power of love triumphs over fate in one of Martin Scorsese’s favourite films which, coming at the end of the war, can also be viewed as a plea for more tolerance and understanding between nations.

1. The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949)

From The Third Man’s humble beginnings (Graham Greene scribbled a single line for the beginning of a story on the back of an envelope), Greene and Carol Reed crafted a masterpiece of a thriller centring around moral ambiguity and betrayed friendships and containing some of the most memorable moments in cinema history. Evocatively photographed by Robert Krasker, post-war Vienna becomes as much a star of the movie as the two principal actors, as hack-writer Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) searches for his friend Harry Lime, insouciantly played by Orson Welles in the rubble-strewn city.

Martins gradually discovers that Lime is an unrepentant racketeer whose actions have had a devastating effect, and it all leads to a memorable climax in the sewers beneath the city. And those other memorable moments? Well, here’s just a few to begin with. Harry’s iconic first appearance, briefly illuminated smirking in a doorway. Welles’ celebrated cuckoo clock speech atop the famous Vienna landmark, the Prater Ferris Wheel. The last scene in the film when Anna walks past Martins in the cemetery. And of course, the famous zither score. It all adds up to one inescapable conclusion. Seventy years since it was first released, The Third Man is Britain’s greatest film.