It is fair to say that Richard Wynne, who died in 1895, would not recognise many recent entries in the art prize that he endowed with £1,000 to reward a “landscape painting of Australian scenery”.

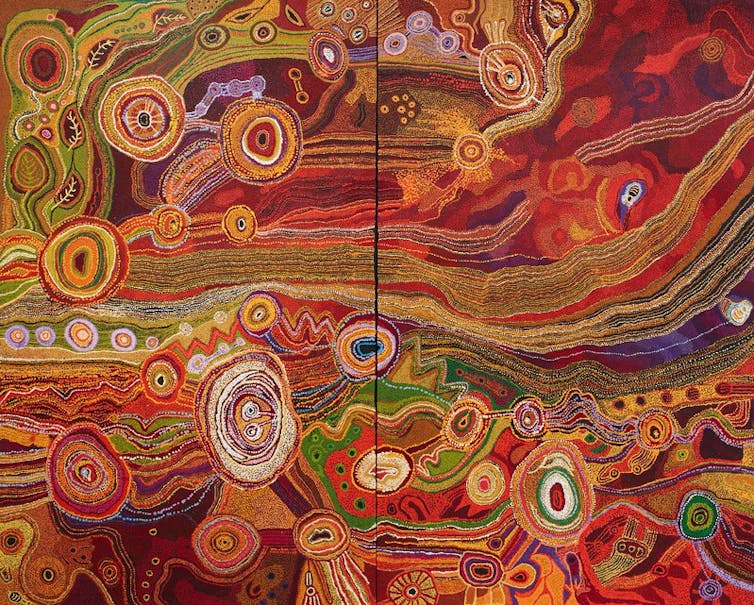

Since 1999, when Gloria Tamerre Petyarre was awarded the Wynne Prize for her magical sequence of Leaves, the Wynne has been dominated by works by Indigenous artists living in communities in central and northern Australia.

Rather than inhibiting artists from different traditions, the presence of such superb art appears to have inspired non-Indigenous artists to also be their best. It is therefore well worth a visit to see the full range of entries in the Art Gallery of NSW’s annual festival of prizes.

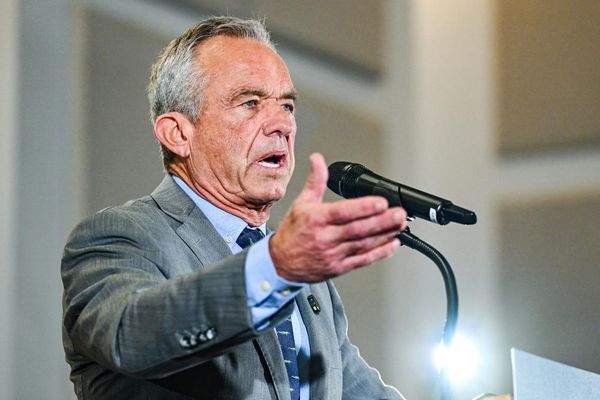

Not all appreciate this liberation of landscape. In 2017, the veteran Australian artist John Olsen attacked the awarding of the Wynne Prize to Betty Kuntiwa Pumani for Antara, a painting of her mother’s Country.

He claimed the “real” Australian landscape tradition was represented by artists such as Elioth Gruner and Brett Whiteley, while Pumani’s painting was of “a cloud cuckoo land”.

From memory this may have been the year that the gallery changed the design of the exhibition spaces so that the most exciting Wynne entries – almost all by Indigenous artists – filled the large central court.

As a young man in the 1950s, Olsen had demonstrated against the reactionary conservatism of the Trustees of the Art Gallery of NSW; in his old age he objected to their openness to new ideas.

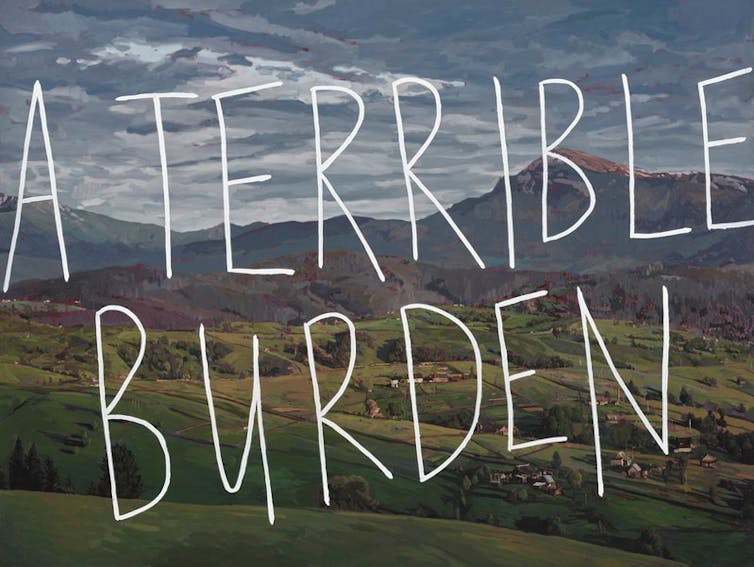

Both Olsen’s pomposity and the dreariness of an Australian landscape tradition that colonises the land was mocked by Abdul Abdullah in his painting A Terrible Burden, a Wynne finalist in 2019.

Abdullah has expressed surprise at Olsen’s strident defence of the conservative tradition of Australian landscape as his own paintings are so abstract, although he tells me “his cultural contribution doesn’t hold a flame to Ken Done, who is very good at painting ‘place’.”

Origins of the prize

As with its more famous partner competition, the Archibald Prize, the Wynne is not quite what its benefactor envisaged.

Richard Wynne’s will originally designated the Art Society of NSW as the body to administer the prize, not the Art Gallery of NSW. In 1895, shortly after Wynne’s death, the Art Society experienced an acrimonious split when a number of artists led by Tom Roberts and Julian Ashton established a rival body, The Society of Artists.

By the time the prize was first awarded in 1897 the executors, Perpetual Trustees, decided it was more prudent to have it administered by the Art Gallery than a group of squabbling artists.

The tensions between artists is perhaps one reason why for many years there was no formal exhibition of entries. Walter Withers was awarded the first prize in 1897 for a painting that had already been bought by the Art Gallery. As he wrote to the Argus:

I was unaware that such a prize existed until I read the telegram in your issue of November 24, announcing the honour that had been done to my work.

A search through both the National Library’s Trove and the Art Gallery of NSW’s digital archive shows that, as with all art prizes judged by a committee, on many occasions considerations other than merit influenced the judges’ decisions.

In 1898 the Trustees began the practice of both visiting Art Society exhibitions and inviting interested artists to deposit their offerings for consideration. This was also the first year the prize was awarded to William Lister Lister, a stalwart of the Art Society (later renamed the Royal Art Society of NSW). He was awarded the prize a total of seven times.

With the exception of the 1898 award, Lister Lister was a trustee and therefore a judge on each of the other six times he won. He was not alone in this.

Sydney Long, a fellow trustee and fellow member of the Royal Art Society, was awarded the Wynne in 1938 and 1940. The only artist to be awarded the Wynne more often than Lister Lister was the South Australian, Hans Heysen, who was awarded the prize eight times. Heysen, from South Australia, exhibited with the Society of Artists.

For many years, it is fair to say many of the decisions governing the Art Gallery of NSW were a fine balance between two competing factions, with each taking it in turn to award the various prizes to their members and supporters.

In 1899, the young George Lambert, associated with the Society of Artists, was awarded the Wynne for his heroic painting of horses ploughing through mud, Across the Black Soil Plains. He was also awarded the NSW Government’s newly established Travelling Art Scholarship, a recognition of his precocious talent.

The eccentric nature of the management of the prize led to the situation in 1921 when the Trustees commissioned Elioth Gruner to paint The Valley of the Tweed, with the prize as a part of the commission.

The cosy duopoly of the art societies was challenged in 1943 after William Lister Lister’s sudden death.

Instead of replacing him with another representative of the Royal Art Society, the minister for education, Clive Evatt, appointed his sister-in-law, the collector and painter of modern art, Mary Alice Evatt, to be the first woman trustee in the gallery’s history.

In January 1944, Evatt advocated for William Dobell’s portrait of Joshua Smith to win the Archibald Prize. The following year she voted for the Wynne to go to Sali Herman’s urban landscape, McElhone Stairs, a painting with a complete absence of gum trees, painted by a Jewish immigrant who exhibited with the Contemporary Art Society.

The Wynne continued to reward interesting paintings when Russell Drysdale won with Sofala (1947), and Lloyd Rees for The Harbour from McMahon’s Point(1950).

A changeable landscape

By the early 1960s, the old exhibiting societies were less relevant to artists trying to establish a career. But the new dealer galleries understood the value of prizes to their artists’ profiles.

The new superstars of Australian art, John Olsen, Fred Williams and Brett Whiteley, began to be listed as prize winners.

The Wynne was still very much a “boy’s club”, as if the Australian landscape could only be captured by one gender. Lorna Nimmo had won in 1941, but her watercolours did not appeal to the Trustees.

It took until 1971 for Margaret Woodward to be the next woman winner, with her painting, Karri Country.

She was followed in 1994 with Suzanne Archer’s Waratah Wedderburn.

(While the prize is most well known for its landscapes, figurative sculptures can also enter, and Rosemary Madigan had won with her classic stone torso in 1986.)

Ann Thomson was awarded the 1998 prize with her abstract painting, Yellow Sound, which may have encouraged the Trustees to cast their net wider. For the following year the Wynne Prize was awarded to Gloria Tamerre Petyarre.

This bastion of the Australian landscape tradition was never the same again.

Easily the most memorable painting to be awarded the Wynne in recent years was in 2016, when the Ken family collaborative painted Seven Sisters, the grand narrative of protecting country.

Although some non-Aboriginal artists have won this century, Aboriginal art continues to dominate. The gallery now also hosts the Roberts Family prize, specifically for work by Indigenous artists.

What we are seeing here in this oldest, and potentially crustiest of art prizes, is concrete evidence of a whole new tradition of Australian art – or rather evidence that the oldest tradition is using art as a means to reclaim the land.

Read more: Australians' favourites show Aboriginal art can transcend social divisions and art boundaries

Joanna Mendelssohn has in the past received funding from the Australian Research Council and the Australia Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.