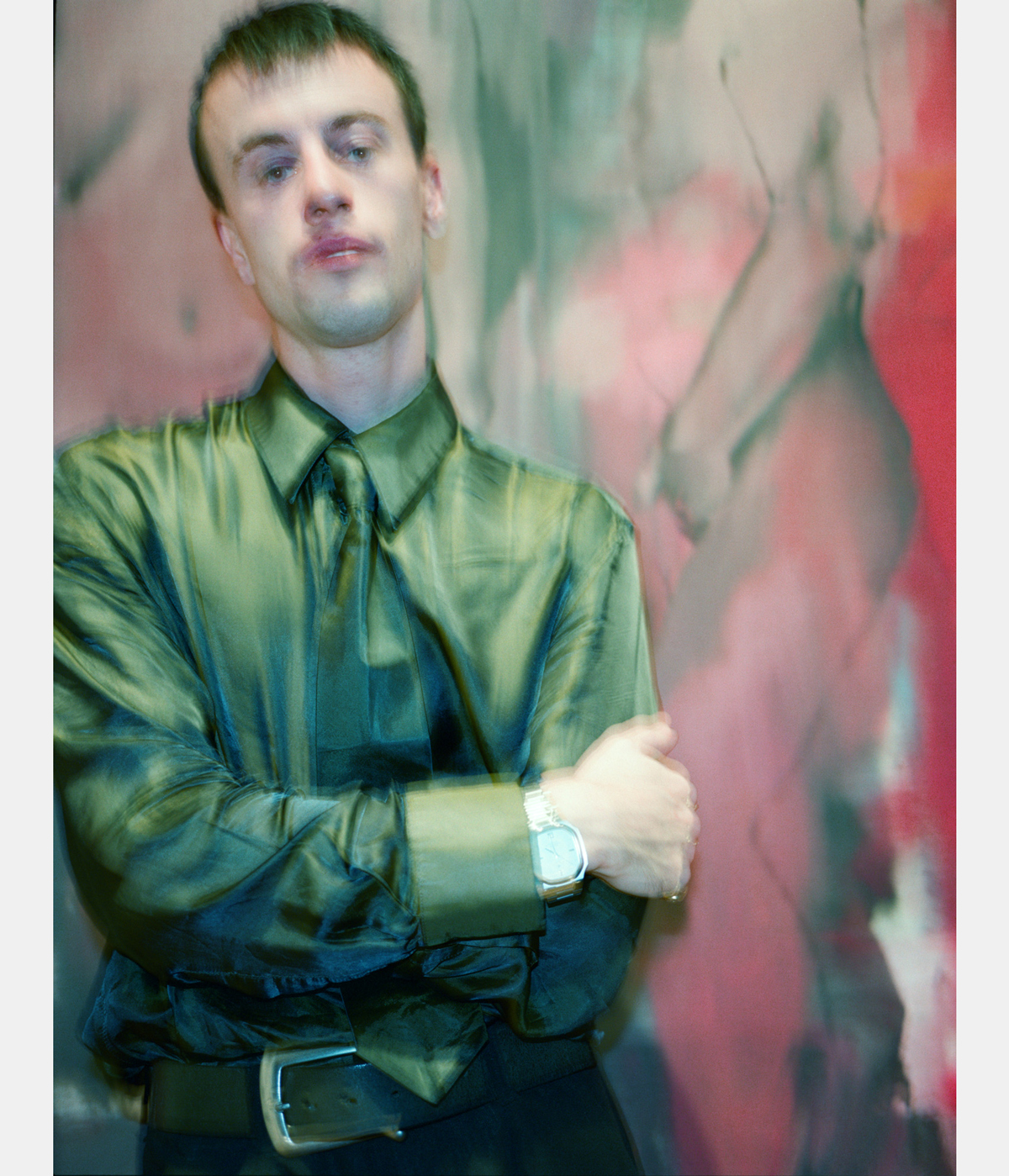

It has been a good year for British painter George Rouy, who, in 2024, became one of the youngest artists to join Hauser & Wirth, in a representation announced in collaboration with Hannah Barry Gallery.

Originally from Kent, he won a place in 2012 to study painting at Camberwell College of Arts. ‘When I was at art school, painting wasn’t as popular as it is now, but it’s had a resurgence,’ says Rouy. ‘At the time, it felt like it wasn’t the cool thing to do, but I went through the process over the years, trying to search for what figuration in art meant.’

After graduating in 2015, he was inspired by French, Dutch and medieval paintings in his early figurative works for group shows. A bold, more confrontational portrait style soon gave way to a deeper concentration in how the paint was applied to the canvas, with Rouy’s thick, instinctive brush strokes lending a thoughtful and expressive edge to his process. It led him naturally to the more abstract style we see today, with the figures in his paintings captured in a state of distorted awakening, as if from a fever dream, a style that has invited comparisons with Francis Bacon. No longer portraits, or specific figures, they are now memories of them.

Rouy traces this fascination with the figure back to his 2023 solo exhibition at Hannah Barry Gallery, when he collaborated with choreographer Sharon Eyal on a live event. ‘It was a turning point when I saw Sharon Eyal’s work,’ says Rouy. ‘It was a massive moment for how I changed my perspective on the way I wanted to approach the figure. When you see her work, it’s very intuitive, heavily emotive, but it’s also incredibly minimal and focused on the body and interactions as a mass – on a group of figures but also on them individually. I walked away from that wanting to erase the clutter and sharpen my focus on the body, and on what that means within painting.’

‘I removed the face because it was becoming too much. Without it, you can assess the whole painting without that focus’

George Rouy

Rouy’s debut show for Hauser & Wirth, ‘The Bleed, Part I’ (currently on in London, with a Part II to follow in LA in February 2025) builds on this exploration of the figurative. Here, the human form is distorted, faceless, often lost in a mass of writhing figures in a contemporary reimagining of 19th-century classical tragedy paintings.

‘There was a clear shift four or five years ago, where I’d always thought about the figure, but then my focus became very much on the body, and the interactions of the mass of figures and multiples,’ says Rouy, who rejects the idea of the body in static isolation, instead depicting it as constantly in flux, in a relationship with both its own limitations and with a mass of other bodies. ‘You then have this anatomy that’s directly transferred into the work through gesture, but also into the representations of figures as well.’

In contrast to many of his contemporaries, Rouy eschews traditional markers of identity to zoom in, instead, on a more universal experience. With no faces or genitals, there is nowhere to anchor the eye; we are therefore invited to gaze, unheeded, across a blurring of movement, colour and texture. ‘I removed the face because it was becoming too much,’ he adds. ‘Without it, you can assess the whole painting without that focus. I wanted to allow the viewer to treat every aspect of the painting with the same value, and I’m very strict on that. Every part has to have purpose, there’s no filler as such. Removing the face allows your eye to look at the bodies, and then the hands and feet become a lot more of a feature and have a lot more of a purpose, and those things get drawn out more than they would when you had the face.’

In the show, we see hints of what’s next for Rouy. Among his bruised palettes of colours, there are, for the first time, some monochrome works, which he refers to as his phantom paintings. ‘I’ve been wanting to do monochrome works for a while, and they haven’t been successful until this recent body of work. I changed my approach, and started to think about illumination and darkness. By using silver-primed canvas or linen, it gives a backlit feel, but I was using charcoal powder, which sucks and diffuses the light. At first I worked with those two components, but as time went on, it became a bit more sophisticated, and it creates a depth when there’s so many layers, which some of the oil paintings don’t have.’

The visceral results become a fluid jumble of life, which appear to drip and bleed their way across the canvas, hence the exhibition’s name. ‘There is this idea of a leakage, or a bleeding out, but also, it is how well our bodies are interacting with the space around us. Within the paintings, there is that dissipation, in the surrounding areas of the bodies and how they blend into each other. It’s important to say that, with the blood, there is the idea of a life force, but these are depictions of mortal humans. They are not anything larger. They are just as fragile and just as flawed as we all are.’

‘George Rouy. The Bleed, Part I’ is on show until 21 December 2024 at Hauser & Wirth London. ‘George Rouy. The Bleed, Part II’ is on show from 19 February-1 June 2025 at Hauser & Wirth Downtown Los Angeles

A version of this article appears in the January 2025 issue of Wallpaper* , available in print on international newsstands, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today