In the quiet town of Cognac, France, on a quaint cobblestone street just off the banks of the Charente River, lies the Musée des Arts du Cognac. The museum recounts the history, savoir-faire, and world renown of France’s most famous hard liquor. The production of cognac began in the early 1600s, and the museum covers everything in this long history from the crus that form the terroir to the painstaking process of building the barrels in which the spirit ages. One exhibit identifies cognac as “a particular favourite with middle class people of Afro-american or Latin origin.” It doesn’t really explain what that means – the fact that cognac’s biggest market by far is the United States, and within the country, African Americans reportedly comprise the largest share of consumers.

Why is that? According to popular media and industry folklore alike, African American cognac consumption dates to either or both world wars. In this telling, Black GIs sent to Southwest France fell in love with the bottled spirit as much as the spirit of a country they perceived as decidedly less racist than home. Journalists offered this origin story in Slate in 2013, and on Medium in 2020.

Social media accounts with large platforms on Instagram and Twitter made the same argument – that cognac appealed to Black soldiers because it was symbolic of the freedom and recognition of their humanity that was lacking in America. Assertions of fact across the internet may not be backed by evidence–but the cognac narrative has travelled far beyond social media clickbait; it has received traction in global newspapers of record as well. This year Le Monde published a story about cognac’s popularity among America’s rap artists, recapitulating the same wartime genesis.

A century-old affair

It’s a lovely story – but it just isn’t true. There is no evidence to suggest that it’s anything more than romantic myth, and the story certainly invites questions. Why would Black soldiers become enamoured of cognac specifically, but not wine, which is consumed much more by the French? Why would Black soldiers alone fall for cognac’s charms, but not their White counterparts? And why would it take military deployment across the ocean to encounter the spirit? Cognac was first exported to the United States in the 1700s, but the wartime narrative recounts that African Americans never set eyes on it until 200 years later.

The truth is, African Americans encountered, served, studied, drank, and sold cognac for at least 100 years before the Second World War. Or even the First World War. Formerly enslaved Manhattan tavern owner Cato Alexander is just one example who brings to life African American knowledge of cognac. At some time before 1811, in an establishment near today’s 54th Street and Second Avenue, Alexander shot to the top of his profession – bartending. Afforded respect that few African Americans enjoyed, for almost 40 years he was celebrated for his cuisine, and even more so for his mixology. But quite apart from Alexander, the narratives we have from enslaved persons make it quite clear that even before the 19th century, cognac and other brandies were part of African American life.

So what’s behind the contemporary African American-cognac connection? The narrative that Black GIs discovered cognac in the midst of France’s freeing ethos of liberté, fraternité, and egalité is an appealing one – but the much more likely and parsimonious explanation is the ruthlessly effective thrust of advertising. Retailers in the food and drink industries have long sought out African Americans with advertising developed to capture the Black consumers, usually at a time when market share was relatively low. Fast food, for example, made initial forays into targeted marketing in the early 1970s; by the 2000s, companies like McDonald’s had entire websites dedicated to consumer segments based on race and ethnicity.

Hip hop and cognac

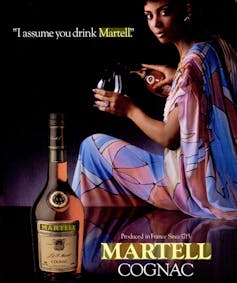

But traditional cognac advertising to African American drinkers began relatively late, in the early 1980s. Print media and outdoor billboards were primary tools in Black-focused campaigns. Among magazines, Ebony was a centerpiece. Founded in 1945 by John H. Johnson as the first nationally-circulated magazine designed to showcase Black success, its pages helped position cognac as the perfect emblem of comfortable Black affluence. Those advertising spreads probably went unnoticed by any Black elementary school children who paged through the magazines sitting on their parents’ coffee tables – but some of those kids would grow up to become the cognac industry’s biggest promoters.

Jay-Z’s 2012 venture as a cognac brand owner with d'Ussé represents the long outgrowth of cognac’s bursting onto the hip hop scene in the 1990s and early 2000s. Artists made references to the spirit ranging from passing mention in lyrics to constructing entire songs around it. Nas claims to be the first to include cognac in his rhymes – for example, “Memory Lane (Sittin’ in da Park)” on 1994’s Illmatic. A slew of others followed, and Busta Rhymes’s and P. Daddy’s “Pass the Courvoisier” (2001) was a game-changer.

The song reportedly produced a 30% increase in US sales and Busta Rhymes denied that he was paid to create the record. Nas became a Hennessy spokesperson and described the relationship in this way:

“I found them and they found me… I never would have expected to go to France, and go to Cognac and be drinking 100-year-old cognac right out of the barrel… Hey, in the beginning I didn’t even know that cognac came from grapes!”

To be fair, most of cognac’s biggest global market – the United States – doesn’t know cognac is made from grapes, either. I didn’t, until I began researching it. Cognac occupies a vexed, chameleonic position in American culture: it figures strongly in pop culture; carries a great deal of gastronomic cachet; and yet is little-known and misunderstood. And though it hails from southwest France, it can seem more American than international.

Perhaps it’s that almost-blank canvas that has invited the mythic narrative about cognac’s Black past. It may not be accurate, but it has understandable allure. It’s a story that casts cognac as part of the family, a marker of freedom, and a vehicle to repudiate American racism. And for that, the spirit of one of France’s most vaunted spirits endures.

Naa Oyo A. Kwate a reçu des financements de National Institutes of Health; Fondation Maison des sciences de l’homme.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.