When people think of eunuchs, someone like Lord Varys from Game of Thrones often springs to mind. Chubby, obsequious and a flatterer, he is involved in court intrigues and manipulates people and events behind the scenes.

These traits oppose military prowess and valour endorsed by traditional models of masculinity across various times and cultures. According to those tropes, a eunuch’s weapon is the whisper, not the sword.

In reality, not every eunuch in the ancient world was a servile, cloistered being. In fact, eunuchs sometimes led armies on campaign, and were entrusted with high-level administrative tasks.

What was a eunuch?

A eunuch was someone whose testicles had been deliberately crushed or excised.

In Greek myth, Cronus (the father of Zeus) castrated his own father Uranus to overthrow his tyranny and become king of the Titans.

Greek historians reported castration as war punishment, and persistently linked the castration of young boys to sexual slavery.

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus stressed the demand for castrated boys at the court of the Persian kings. But the market for eunuchs was evidently larger than just the Persian court.

The Romans replicated the Greeks’ negative view of eunuchs. They are often portrayed in Roman texts as being in the company of “bad” emperors such as the supposedly cruel and narcissistic Domitian – even though he forbade the practice of making eunuchs.

The notion of the unmanly eunuch in antiquity was reinforced by Orientalist literature, which imagined ancient eunuchs in charge of something akin to a Turkish sultan’s harem. Unable to procreate, the eunuch is paradoxically surrounded by beautiful women, his in-between-ness granting him access to the psychological makeup of both genders.

Orientalism drew inspiration from historical accounts written after the Greco-Persian wars, which the Greeks won in 449 BCE. These accounts were written in the shadow of Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Near East (including areas such as modern-day Iraq, Iran and Syria), which was followed by the Roman hegemony.

Instead of critically evaluating the sources, colonial writers and their readers indulged in a world of fantasy where eunuchs offered a sensualised peek into the “secrets of the harem”.

In fact, a deeper look at the historical record reveals that eunuchs often occupied positions of great military power and civil authority.

Eunuchs as bodyguards, enforcers and governors

Cyrus, the first Persian king (590–529 BCE), praised eunuchs for their reliability. He insisted that gelded men, like gelded horses, are easier to control. He believed they made up for their lack of physical strength with their loyalty.

Cyrus may have owed his life to eunuchs, who played a role in saving him as a baby from a murderous plot by his grandfather.

The Greek historian Herodotus also reports that eunuch-bodyguards tried to protect, albeit unsuccessfully, the man on the Persian throne just before Darius the Great took power in 522 BCE (Darius contended that this man was not a real king but an imposter).

The historical record also mentions a Persian eunuch being in charge of a garrison at Gaza around 332 BCE.

The Egyptian pharaoh Amasis, who reigned in the sixth century BCE, also relied on eunuchs to recover fugitive slaves.

Eunuchs appeared in the courts of the Hittites and Assyrians (civilisations in modern-day Turkey and Iraq respectively) from the 13th century BCE.

Assyrian kings often appointed eunuchs as provincial governors. The Assyrian king Shamshi-Adad V (who ruled Assyria 824–811 BCE) praised his chief eunuch Mutarris-Ashur as “clever and experienced in battle”. Mutarris-Ashur led the Assyrian army on a military campaign to the Nairi lands in the Armenian Highlands.

King Ashurbanipal, who ruled the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE to 631 BCE, sent his chief eunuch on missions against neighbouring Mannea (a kingdom in modern-day Iran) and the rebellious Gambulu tribe in ancient Babylonia.

Bagoas the eunuch

In the fourth century BCE, there was Bagoas, a Persian court eunuch who is sometimes conflated with a eunuch lover of Alexander the Great who had the same name. Bagoas became the second most important person in the Persian court, after the Persian king.

Bagoas had served in Persian king Artaxerxes III’s campaign against Egypt, and rose to the rank of Chiliarch (the leader of the royal infantry guard).

Bagoas developed a reputation as a kingmaker – he was instrumental in replacing Artaxerxes III with his son, Artaxerxes IV. He later poisoned Artaxerxes IV and installed as king Darius III, who was eventually defeated by Alexander the Great.

Bagoas had plotted to replace Darius too, but Darius outsmarted him; he forced Bagoas to drink the poison the latter had prepared for Darius to drink.

Eunuchs in Rome

Despite the bias of the Greco-Roman sources, including their suspicion of eastern cults that involved eunuch priests, eunuchs were important in Roman imperial service.

The emperor Claudius rewarded his eunuch Posides for his service during Rome’s invasion of Britain in 43 CE.

In 399 CE, the eunuch Eutropius became a powerful consul in Rome’s eastern empire under the emperor Arcadius. Some Romans, however, attacked the appointment of a semivir (half man) as consul as an abomination.

In early Christianity, the concept of becoming a eunuch for the kingdom of God acquired currency. According to some interpretations of the Bible, being a eunuch was connected to the virtues of chastity and celibacy.

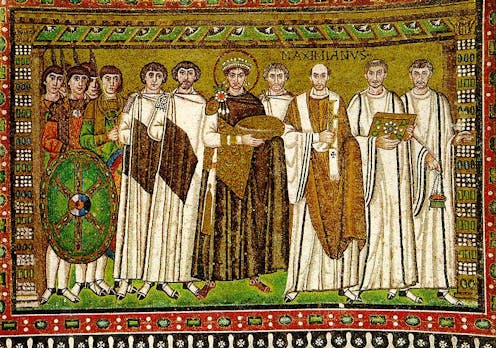

By the sixth century CE, Byzantine eunuchs found themselves in charge of large armies. (What we now call the Byzantine Empire, or the Eastern Roman Empire, was known by its people as the Roman Empire until 1453 CE).

Narses was a eunuch and one of the Byzantine emperor Justinian’s great generals. He managed to recapture Italy, including Rome, from the Goths (a Germanic people who had invaded Italy).

Narses, possibly an Armenian by birth, was no armchair general. At the battle of Mons Lactarius (552 or 553 CE), Narses fought on foot with his fellow soldiers against the Goths. He encouraged his men to hang on against a brave enemy.

Despite the stereotypes, eunuchs clearly often played important roles in the ostensibly masculine world of strategic planning and combat.

This plurality of masculinities in the ancient Mediterranean world remains relevant to modern society as it challenges notions of a simple gender binary.

Eva Anagnostou-Laoutides receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Gerda Henkel Foundation.

Michael B. Charles does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.