Many government-employed economists don't have the training to spot the economic equivalent of homeopathy. Policymaking would be better if they could

Opinion: If a lot of the Government’s health policy people started looking warmly at homeopathy and other kinds of medical pseudoscience and woo, we’d all recognise that as a problem, right?

Maybe we would want to test our intuitions about it. Perhaps the science had moved on. How to check, for those of us who are not medical experts? We could ask the academics working in our medical schools what they think.

READ MORE:

* Do politicians need economics degrees?

* Think Big, the sequel

* Why our economy is too important to leave to the experts

If those academics were predictably dismissive, we might worry about what was going on over at the ministry.

The same is true about economics and economic policymaking. And the New Zealand Association of Economists’ latest member survey (NZAE) is very worrying.

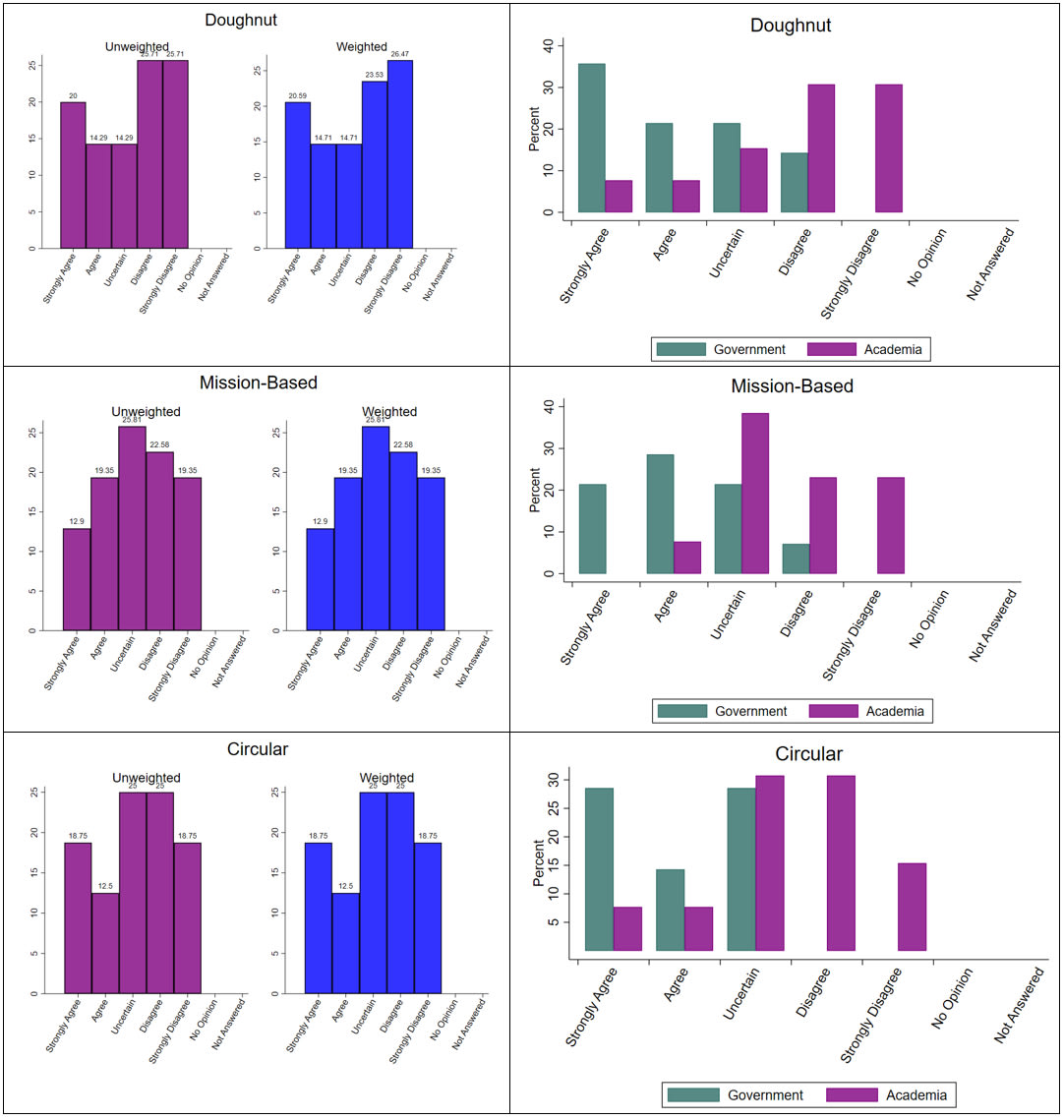

Government-employed economists who answered the survey tended to favour, or be uncertain about, fringe concepts such as doughnut economics, mission-based economics, and the circular economy, whereas academic economists tended to disagree or strongly disagree that these concepts improve economic policy analysis.

The difference is very sharp. Before getting to the numbers, it’s worth considering where the academics are coming from. They do know what they’re talking about.

What unifies economists across fields, countries, and schools of thought is the approach to research: develop a theory and rigorously test it. If the data does not support the theory, develop a better one.

Studying economics to an advanced level has a high entry cost because of the technical nature of the discipline. For the largest part of the 20th Century, economic rigour was shown by developing and debating mathematical theories. The empirical revolution in economics, or the “credibility revolution”, which focused on using statistical methods to draw causal conclusions from data started during the 1990s, shifted this focus, and increased the relevance of economics for policy making.

This consensus approach on how economists work appears to be under attack in various ministries. This trend has the potential to have devastating effects as it can lead to policy recommendations not based on rigorous, scientific methods.

Fringe concepts such as Kate Raworth’s “doughnut economics”, Mariana Mazzucato’s “mission-based economics”, and the concept of a “circular economy” are increasingly used in ministries.

For example, Treasury hosted Raworth as part of its Wellbeing Seminar Series. Mazzucato’s work features in MBIE policy work on mobilising investment to achieve climate goals. And MBIE is also tendering for four research projects to “deliver strategic insights and evidence about the Impacts, Barriers, and Enablers for a Circular Economy”.

If these new theories are to be forming the basis for policy, it is worth checking whether they are sound.

The NZAE asked its members, in its latest survey, whether each of these concepts would improve the quality of economic policy analysis, whether a higher weight should be given to these concepts within the process of the analysis, and whether these concepts should be taught as part of the economic curriculum.

Most respondents disagreed (54 percent) that doughnut economics improves economic analyses and only 19 percent agreed. For mission-based economics, 40 percent disagreed, and 25 percent agreed. Finally, for the circular economy, 52 percent disagreed that the concept improved economic analysis, and 22 percent agreed.

Overall, economists seem sceptical about these theories. But the difference between academic and government-employed economists is stark.

The proliferation of non-scientific concepts in economic policy analysis is a hugely disturbing and dangerous development. It opens the door for biases and ideology to enter the policy analysis process and, therefore, can lead to bad outcomes and costly mistakes

To summarise the findings: government economists tend to agree or be uncertain that these concepts are useful and should be taught, whereas academic economists tend to disagree.

NZAE members were asked whether putting more weight on these concepts would improve economic policy analysis. Academics were very sceptical; in all cases, their most frequent response was “Strongly disagree”. Government-employed economists were more likely to be uncertain, or to agree – sometimes strongly.

Similarly, large proportions of government-employed economists either strongly agreed or agreed with adding doughnut economics, mission-based economics, and circular economics to the core economics curriculum. Academic economists rarely agreed. As one respondent put it, “As an economics lecturer, I am loth to introduce non-science-based concepts into the curriculum.”

It is not surprising these fringe concepts fall on fertile ground in the ministries. They provide more leeway for telling ministers what they might want to hear.

These kinds of populist concepts have a great appeal: they are intuitive and can be read as bedtime stories. They have heroes and villains. They do not feature difficult mathematical models and cannot be empirically tested

And when an academic background in economics is often not required for new economic analysts, we should not be surprised when non-scientific concepts are embraced. Many do not have the training to know when they are dealing with the economic equivalent of homeopathy. It also explains greater uncertainty about the concepts among government-employed economists.

These kinds of populist concepts have a great appeal: they are intuitive and can be read as bedtime stories. They have heroes and villains. They do not feature difficult mathematical models and cannot be empirically tested. And who would not prefer reading “doughnut economics” over “quasi-maximum likelihood estimation and testing for nonlinear models with endogenous explanatory variables” (by the way: a very relevant method for policy analysis)?

Relying on these fringe concepts gives the policy analyst a carte blanche, in that every policy can be justified using these concepts. It gives bureaucrats and politicians a rationale for ignoring evidence and implementing any policy they want.

Overall, the proliferation of non-scientific concepts in economic policy analysis is a hugely disturbing and dangerous development. It opens the door for biases and ideology to enter the policy analysis process and, therefore, can lead to bad outcomes and costly mistakes.

And though supporters of homeopathy may argue that academia is biased against their views, it’s more likely the case that reality just doesn’t support their models of how the world works. The same is true here.

Good policy analysis requires expert understanding from different disciplines. Just as we need doctors to know medicine and engineers to know engineering, we need our economists to know economics. The rigorous process of economic research and economic policy analysis ensures we avoid costly mistakes.

This does not completely let the academics off the hook. Just as we might ask hard questions of a medical school whose graduates prescribed snake oil, academic economists should ask themselves why some of their graduates seem prepared to prescribe economic snake oil.

Policymaking would be better if government policy analysis could tell the difference between medicine and homeopathy.