My maternal grandfather was an artist who was a sign-writer.

On commission, and under the eye of the public, he painted

the giant Queen Elizabeth for the 1954 ‘Royal Visit’

and the giant Captain Cook (with map of ‘New Holland’)

for the 200th ‘celebrations’. These lines, read on their own,

state facts. The rest of the facts are implied.

I expect implication from art. What these massive

portraits stuck up on buildings in the Terrace —

not a symbol, but the act of retaining it symbolic —

imply beyond drawing attention to ‘monumental’

occasions of imperialism, is painting as diversion.

Grandpa was highly skilled at his job. He migrated

from London at 12 in 1913 (‘just before the War’)

and kept London in his head all his life. Everybody

liked Bob. His brush only did part of the talking.

(John Kinsella)

My maternal grandfather was a station hand

He went to Perth in the 1950’s, he had tuberculosis

I never heard of him doing any paintings but his

Daughter Aunty Mary was a magical bark painter

Stripping tree bark, using Indian ink and pressed flowers

Aunty created the most beautiful bark paintings

Mullewa CWA hosted her exhibition in Mullewa

Aunty was also a station house maid as a young woman

Just like her mother and older sisters were back then

Mum said they both served the Governor General out at

Minilya Station dressed in white hats and white aprons

I wonder if they had dreamt of creating art or paintings?

I wonder if they could dream of being creative in those times?

(Charmaine Papertalk Green)

–Art Yarn

When they become public, acts of collaboration in poetry are more private than it might seem. As with all collaborations across the arts, there are the behind-the-scenes conversations that go on behind the “making”, and there are inevitably issues of where it is “work” and where it is “friendship”.

Many people collaborate without personal bonds being created, and many come to collaboration because of personal bonds. There are professionally encouraged or negotiated interactions, of course, but the creative collaborations I have been involved with have primarily come out of personal interest, or through a creative and ethical respect.

I can never specifically answer for the interests or motives of my collaborators, but I can say that in the case of persistent collaboration, we inevitably work out where the other “is at”, and quickly take on something of the rhythms of each other’s lives in order to communicate and make. This doesn’t necessarily mean a deeply personal intimacy with a fellow participant’s life, but it does mean an awareness of the ebbs and flows that affect their creative practice.

I start with this “declaration” because what I discuss here is necessarily one-sided in what, ultimately, can never be a one-sided statement. I have collaborated with many poets, writers, musicians, artists, activists and workers, and each collaboration is its own thing, but here I wish to talk about three long-term, ongoing ones.

Read more: Can poetry stop a highway? Wielding words in the battle over Roe 8

A Venn diagram

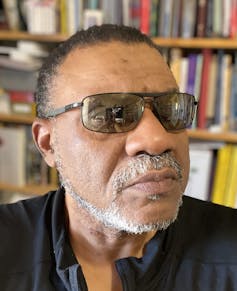

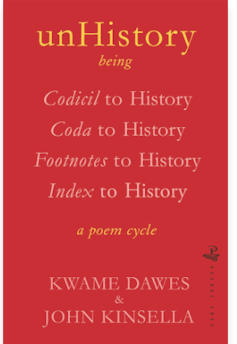

Since 2014 I have been working with Ghanaian-Jamaican poet Kwame Dawes who grew up in Kingston, Jamaica, and lives in Nebraska, USA, on a series of books. Its most recent iteration is in unHistory, a long poetry work in four “books”.

Concerned with addressing the inequities of privileging certain views and interpretations of history by the powerful, Kwame and I spent a couple of years swapping poems on a regular basis, tracing personal experience and received notions of “the historical” to create a dialogue but also a Venn diagram of ethical and creative concerns.

He and I started using this technique when I was living in Ireland in 2014 and Kwame was in the US. I had lived in Ohio for a number of years in the early 2000’s, so that was another subtext of our dialogue.

Using a format wherein we echo each other’s poems, and then veering off on our own personalised tangents, we sought to build a large pulsing work that was neither archive nor record, but a collation of utterances and interpretations of contemporary and past events, often mediated through music, literature and our own personal journeys.

Both sharing a deep commitment to decolonising and confronting social injustice, as well as caring for the state of the world’s ecologies, we found our differences of experience helped clarify our ways of discussing the issues we were writing about.

1.

This is not my history, but people call it history

as if it belongs to all of us, detracts from us, builds

us into what we are and what we’re not. Those dates

that pin lies as truth, that make fact emanate over

fallout. Whose history is made in the telling?

Whose is morphed into the bubble of nitrogen

on the root of a legume in a field tilled down

to its relics, yielding wars and the charred offerings

of campfires? These stones that cut our feet, transport

us during a museum visit, behind their glass,

labels slipping, or the digital bands of now

breaking up. I am here at the end of one

possible scale, carbon dating my learning,

my teaching. Land, sea, land. Dilution of days.

JK

2.

For Toni Morrison

I do not know how to mourn what I have only

barely consumed, and by consumed I mean

the eating, the settled rest after chewing

and delighting in the sudden first sweetness,

the unfamiliar growing into greater sweetness

until I know before the first swallow that my body

will never be satisfied without this food, this food

set out before me. And I horde that pleasure,

that knowing, kept it for the secret place

of empty roads, of unfurnished rooms, of lanes

with no names, of a world where the whisper

of electric sensors has overlooked. I do not know

how to mourn her language, her art, her music,

her wizened beauty; but this hunger, this deep

throbbing hunger is my belly’s elegy, and history

is the persistence of tyrants while the poets die.

KD

The poems vary from strict verse forms (including Spenserian stanzas used in anti-colonial iterations) to quite open lyrical structures, and move across different modes of expression to allow us to venture into spaces we may not venture into alone. Well, maybe we do alone, but if so, differently.

As Kwame says,

We wrote unHistory through a poetics of immediacy, a practice of writing about and in the various moments that we were living through, and poetry, for me, anyway, became a way to know where my heart and mind was … a way to find language to engage this moment.

We constantly discover things about ourselves – that’s the essence of friendship, I think. Of speaking and being heard, of listening and find new ways to speak. It’s essential that a strong creative mutual respect and empathy exists, but in the “projects” I work on, an ethical overlap is equally essential. The poetry that comes out of the interaction must be more than a curatorial object, more than a creative moment shared, and certainly more than a publication or event.

Snow-sparked days and solipsism

Kwame’s poetry has a depth of spirituality and storytelling that overwhelmed me (in the best possible way) when I first encountered it, and I find myself swept along by its solid and complex rhythms, by its modulated tones and immense range of encounter. He is always willing to encounter the friend as well as the inimical person, and respond with penetrating insight, great generosity, but also absolute frankness.

His is a poetry of humanity. To read a Dawes poem is to draw the public and private closer. Language comes alive and sound echoes sense – it’s vibrant, deeply informed, and generous with its verbal painting. How does one entwine with this?

Well, you do and don‘t entwine. You reply or respond to the whole, or you start a new thread, you echo a line or a thought, or you offer new lines and new thoughts. A kind of exchange takes place that might similarly take place in person should we be in the same real or virtual room, but inevitably takes place in emails.

40.

It has snowed, again, and the street is white;

such light, such startling glaring light,

bounces off the fresh covering. I can’t write

my poems without this framing. It is bright

winter here, and even my secret diet

of morose distraction must now succumb

to this snow-sparked day. It’s not my birthright,

this landscape, where breathless cold consumes

and shapes all, but I’ve learned the art of adoption.

KD

41.

So much we recognise but then undo

so much we might love but undo – stories

of lives connected to our own but too

unalike to draw into new stories,

though these might actually be the stories

of our origins, these might be a form

of personal history – families,

those inherited traits, mannerisms

that almost catch us out in our solipsism.

JK

Kwame’s and my poem creations are about getting to know each other over a distance. And we do know each other, and we are, I think, the deepest of friends. So … he and I have not really spent physical time together outside Zoom interactions.

I have actually met Kwame in person, but he doesn’t recall the occasion – it was a brief encounter in South Carolina about 16 years ago. We have been meant to connect and read together in public on various occasions, but things have stopped this happening, especially over the last couple of years the pandemic. We read in the public of “Zoom” these days!

But when you’ve written five books together, and you swap poems constantly and discuss poetics, and share so much in common whilst being so different in life experience, you know each other.

Part of making the work together is “weaving” the poems together, but weaving has different forms. Kwame and I work through a call and response mode of making, where our poems talk to each other’s poems in chronological sequence on a daily/weekly pattern.

‘Mixing’ with Thurston Moore

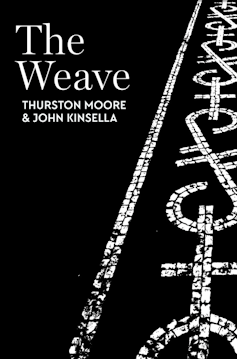

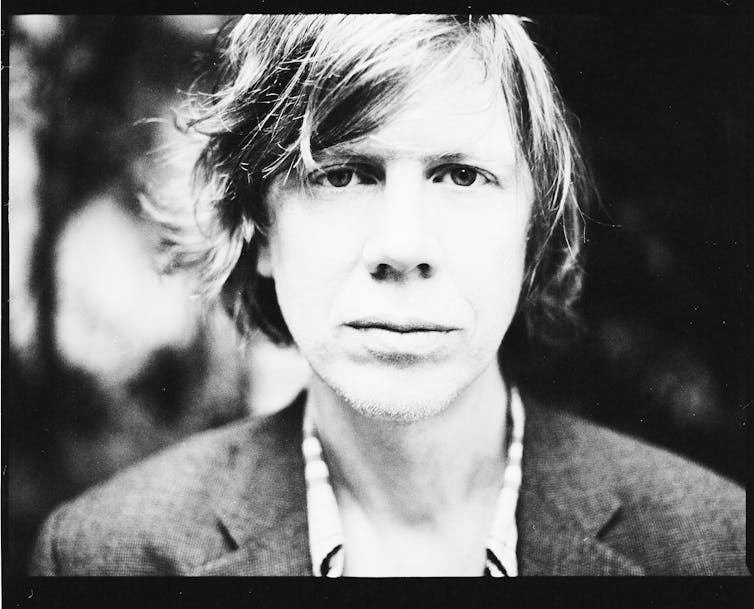

But with Thurston Moore, American musician and writer who was co-founder of the band Sonic Youth, it is more a literal case of weaving lines and stanzas together to make shared poems.

The Weave is the name of our first full-length book together, which is mainly poetry but also includes photos and conversation. We have, however, done two shorter works over the years and are at present weaving our way towards a new work.

It’s a slow process as Thurston is often busy with his music life, and though the poetry is an intrinsic part of this, there are demands on his lines and they come when they come. I am usually ready and waiting and they are “mixed” into the poem we are working on at the time.

During an interview we did for Poetry magazine, Thurston mentioned that at first he found the “mixing” process to be a little confronting or disconcerting. I took that on board and we increasingly create poems in stanzas responding to stanzas, with mixing taking place around the edges. That’s part of a process of shift and adjustment and expanding the possibilities of a collaboration.

Wild Nights Out

Engulfed by painkillers, we shriek a way out of the envelope –

never alone at the pulpit, shimmering across the stage,

slipping through cracks in the green room, bracing

nights after asteroids in Kurt Schwitter’s vocal memories.

Striptease fanzine found in storage and someone’s also

listening to john mcgeoch’s guitar playing on a loop…

the same things are never the same

the things are the same never

same things are same the never

never same the things same

things same never the same

same the things the never same

A return to sender stamped from an angel their frosted eyelashes filters and protectors

Who rolls and tolls with the lost and holy soul of Jerusalem? Cash. Johnny Cash.

Possibly.

the same things are never the same

the things are the same never

same things are same the never

never same the things same

things same never the same

same the things the never same

Yes, for sure. Spandex security blankets dig deep

into hymn metre and dash across the intersection –

but take the bypass to level one and syndicate?

No way, no way known, & not a hope in Hades…

the same things are never the same

the things are the same never

same things are same the never

never same the things same

things same never the same

same the things the never same

Music

There’s obviously very often a concern with music in our interaction (as there is in my interaction with Kwame), but also with the dynamics of the performative and social commentary. A strong immersion in the purposes of the avant-garde, of letting meaning also generate out of juxtapositions and elisions, make for an exciting dynamic where the text can take us anywhere. And being a slow, gradual process, it can take a sharp turn just brought about by a long gap in interactions.

I first swapped a few emails with Thurston around 2000 and wrote a poem about Hamlet and Sonic Youth which I sent to him.

He doesn’t remember this in particular, and our first in person interaction was in 2007 when Sonic Youth was in Perth to perform Daydream Nation for the Perth Festival. My partner Tracy and I had been given tickets thanks to Lee Ranaldo with whom I had some contact, and at one stage I was hoping to edit a volume of his dynamic and innovative poetry.

Backstage after the (brilliant) concert, we met up with Thurston and Kim Gordon who were about to fly out. Not long after, I took Lee and Mark Ibold (bass/guitar player with the band) or a tour of the wheatbelt, and they visited where we lived just outside York.

Lee took some incredible photos of Yenyenning Lake and I wrote poems. Thurston got to see a bit of the wheatbelt the day before the concert, I think, but I might have the timetable messed up there.

Read more: Writing the WA wheatbelt, a place of radical environmental change

But when I really got to talk with Thurston was when he and his partner Eva came up to Cambridge as part of a series I was running in which I tried to discuss the relationship between music lyric and poetry with lyricists/musicians. It was a bit of a “wow” event, and Thurston really bridged those gaps.

He is a collector of chapbooks and small poetry publications, and his intense music avant-gardism was alive and well in his poetics. He read and was actively involved with the New York poetry scene, as well as teaching at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Colorado, and had worked with a poet I greatly admire, Anne Waldman. Music and poetry run in the same stream! It struck me that we could do some really interesting things as poets. And not long after that we started making poems, and we are still making poems.

See that kid diving off the PA stack

mid-air he knows the time time

to state the case for

beauty and its ordained worship

believe him, in him, for him

her waves hymns radios singing

her exquisite notion of peacetheir love of the moment when twirl

and suspension almost eludes the process

but synch those riffs and blastbeats

in swan-machines to bloom eternally,

century on century of Agave ocahui brilliance.

(from Ballroom Dance Rush)

A commitment to decolonising

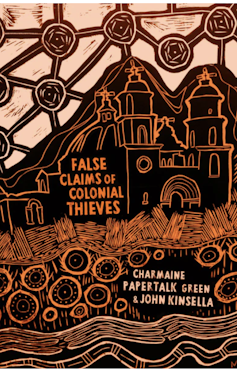

When Charmaine Papertalk-Green and I published False Claims of Colonial Thieves some years ago, it was the coming together of a long journey to understanding and sharing. As a Yamaji poet with strong ties to her community in Geraldton and Mullewa, Charmaine’s intent as a poet is very much located around her country and her people.

Coming from a colonial-settler background, and therefore part of the oppression and dispossessing, no matter how much I reject and try to negate this part of my heritage, I necessarily represent an antithetical figure in Charmaine’s writing.

But she and I share an absolute commitment to decolonising and to addressing the wrongs of the past through trying to make the present more just. We are also both fierce opponents of the exploitations of the mining industry, and, what’s more, enjoy a good story, a good yarning. Over the years I feel we have become good friends – a friendship come out of commitment and, I think, mutual respect. Respect is everything.

I spent the last three years of my high-schooling in Geraldton, my mother lived there, my brother, a shearer like Charmaine’s father, still lives there with his wife. My father managed a massive farm near Mullewa for a while, and I was no doubt up there for holidays at the same time Charmaine was in Mullewa town.

I originally connected with Charmaine looking for a relative of hers who was a Senior lawman, and from that point we started our conversation.

Charmaine and I built False Claims over many years. The core approach was to swap stories about experiences or issues and let their differences sit alongside each other. The Yamaji experience and the “settler” experience juxtaposed in ways that exposed the injustices and crimes of colonialism.

The main sequence in the book was based on the architecture of the much lauded English architect and priest Monsignor Hawes and how the wonders of his localised buildings in WA are exemplars of pain to Aboriginal people – with regards to the overlaying of Indigenous spirituality, but also material occlusions of occupation sites such as quarrying stone from spiritually significant country.

Taking our personal experiences of those churches and buildings into the dialogue, we tried to make a different kind of timeline that respected many voices. The book works by placing different voices alongside each other to sharpen focus on issues.

Some poems like Undermining place our voices in conversational proximity while remaining themselves in the same poem.

Undermining

- JK

The king brown does not die from its own poison — within its body, inert.

Uranium within the hold of old ground around Wiluna is more than history. Leave it there. Intact.

The roo-tails sign the ground with making, and then they moved on and back until stopped in their tracks.

We try to find our way through the world avoiding reactors. Terms of trade are weapons-grade.

Or see the range folding inwards, burst back out. Scrub, forests, their contents. All gone. Hole.

Lure of the material — to conjure empathy out of furnaces. Giving rise to religions honed as bayonets.

Quarry expanding to echo round owl rock its footing shaky and mice sharp as shrapnel.

- CPG

Balu winja barna real winja

Real old ones them ones

Old ground our country

With ancient ones deep within

Wrapped tightly away

For the earth protecting

Itself from itself knowing

It can die from its own poison

Earths silver grey hair

Elder belonging to a time

When the earth was soft

The little boy went to sleep

Balu winja barna real winja

Real old ones them ones

Man is a greedy monster

Interfering to satisfy self

Pulling old ones to surface

Birthing a dangerous little boy

Naming after a god and

Worshipping like a god

For the warfare toys of

Other little boys worldwide

Energy, power, death, destruction and money

Uranium is safe in the earth

Like a sleeping Elder

Balu winja barna real winja

Real old ones them ones

Both of us combine against the rapacious greed, the country-damaging impetus of the mining companies and their false talk. Always there’s the dialogue and the issue of respect for difference, of being aware of the appropriation of Indigenous knowledges and creativity by the colonial machine.

Permission and country

There are a lot of places I can’t and won’t go, and I leave plenty of things to Charmaine to work through. A lot is just not my business and I don’t seek to make it so.

Charmaine is generous, but very defined in her boundaries, and I know and respect this. We are not each other, we are different, of course, but we also get that and make it work. The mediating and strong voice of our publisher, Magabala books, is also present in the journey towards a decolonised justice.

Over the last two or three years, Charmaine and I have been working away at a new book, called ART. We have had the good fortune in pandemic time to be able to catch up in Geraldton for a couple of days in person, and yarn over how things have been going with it. Family is part of who we both are, and it’s nice to connect with family in the making of this.

Charmaine has her own issues about how she positions herself with the art we’ve been writing about, and as an artist, about how she brings her art into the book. I have constant issues of permission and country to negotiate, but that’s also part of my day-to-day life living on stolen land I also love but know I love under false conditions.

I am grateful, deeply grateful, to Charmaine’s profound knowledge of country and culture to allow me some ways in, as I am grateful to other traditional owners and custodians for knowledge regarding their lands.

Collaboration is an ongoing act of making, even long after the work has finished. How we interact and make “art” with others implicates them and ourselves in the making, and that carries vast responsibilities.

We not only speak for ourselves, but our cultural experiences and our ethical concerns, for the lands we write, and for the social worlds we are part of. And we also always speak for the biosphere. This in itself gives meaning to acts of collaboration, as well as sharing and intensifying responsibility.

John Kinsella receives funding from the Australia Council. I publish with Peepal Tree Press, Magabala Books, and the University of Western Australia Press.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.