In October 1975, at a talk in Wollongong, Frank Moorhouse discussed the first project for which he deliberately undertook archival and historical research – a feature film called Between Wars. This process would become integral to Frank’s work.

It would culminate in his celebrated “Edith trilogy”, which followed the League of Nations (a forerunner of the United Nations) from the 1920s through the 1940s, then the establishment of Canberra as our nation’s “Capitol” in the 1950s, through the fictional Edith Campbell Berry.

In Wollongong, Frank discussed balancing what he called “the historical element” with the “the narrative element”. In his notes for that talk, he wrote: “When the facts conflict with the legend print the legend.”

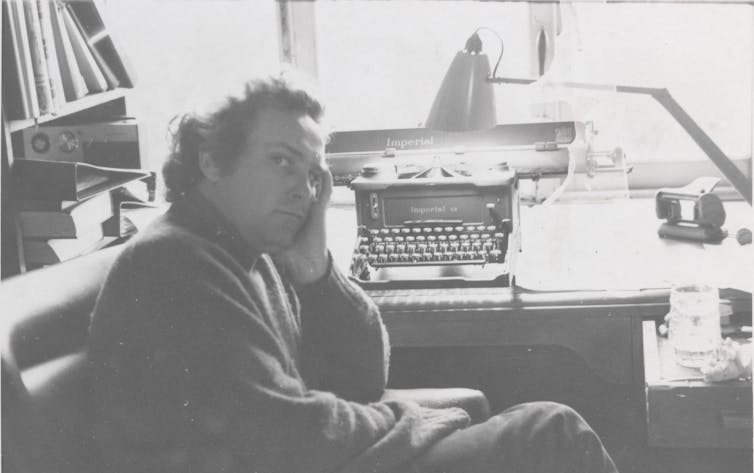

Since 2015, I have been working on a two-volume biography of Frank Moorhouse. This has involved its own process of archival and historical research.

But biography is a sub-field of history. For a biographer, when the legend conflicts with the facts – print the facts. The problem is that establishing the facts, and disentangling fact from legend, is not as straightforward as one would hope – especially when the subject is a protean figure like Frank Moorhouse.

When initially considering this project, I realised although I had read many literary biographies, I had never really considered how biographies are written. I took for granted certain aspects of the process, which involve complicated, time-consuming reconstructions.

Take, for example, establishing a seemingly simple timeline. I first pulled together a basic chronology of Frank’s life from various public sources. I found nearly 2,000 articles referencing Frank, which included public statements by and about Frank. There were interviews, reviews and news reports on various activities he was involved in.

Frank gave me a 30-page curriculum vitae. He had also written various pieces of memoir over the years. This allowed me to define the scope of the project.

I also started working through Frank’s archives. The initial plan was to integrate the general outline I had pulled together with the more detailed contents of the archive – to use the outline as a method to organise the archival material, a form of call and response.

This proved to be wrongheaded and embarrassingly naïve.

Increasingly, the archive contradicted both my outline and the public sources. Additional research was required to establish otherwise simple facts and sequences of events. There were two seemingly trivial moments, in particular, that forced me to reconsider nearly everything.

Read more: Bringing Edith home: Frank Moorhouse's Cold Light

‘I speak for Whitlam at the Opera House’

In 1980, Frank edited Days of Wine and Rage, an idiosyncratic anthology of the 1970s. One section opens with a reference to Gough Whitlam’s dismissal on November 11, 1975. The second piece is an excerpt from Donald Horne’s Death of the Lucky Country (1976), a book about the dismissal and the subsequent federal election on December 13, 1975.

The first piece, however, is by Frank, titled: “I speak for Whitlam at the Opera House”. Frank writes about a lunchtime rally that took place at the Sydney Opera House, with 3,000 people inside and 8,000 people outside. After, at the Journalists’ Club, Frank immediately fell asleep – from “the suppressed tension of it all”.

I wanted to include this anecdote in my biography because of something it illustrated about Frank’s character. He was a very shy person, riddled with anxiety and what he referred to as “verbal impotence”, particularly when speaking to an audience. What is interesting about Frank is that in spite of this, he forced himself to engage publicly, at cost to himself.

The problem? The only corroborating evidence for this incident was a letter Frank wrote to his ex-wife in June 1974 – 18 months before Whitlam’s dismissal. There was no rally at the Opera House following the dismissal, though there was a campaign launch there before the December 1975 election – which Labor lost.

And there was such a rally in May 1974, the week of the 1974 federal election – which Labor won; one month before Frank wrote about the event to his ex-wife. The anecdote holds, but the context, and more importantly, the date of the anecdote – and where it fits in the sequence of Frank’s life – is very different.

Read more: Jenny Hocking: why my battle for access to the 'Palace letters' should matter to all Australians

Nude sunbathing and copyright

This made me reconsider a second trivial anecdote, regarding a landmark copyright case Frank was involved in. In September 1973, a story from one of Frank’s books was photocopied without his permission in the library at the University of New South Wales.

In October 1973, Frank first met with David Catterns and Peter Banki, from the Copyright Council. They had engineered this violation in order to bring a test case before the courts, arguing that copyright holders should be paid for their work being copied and used.

The court case took place between April and May 1974. Moorhouse and Angus & Robertson (Publishers) Pty. Ltd. v. University of New South Wales was part of a larger strategy that eventually led to the establishment of the Copyright Agency Ltd, a not-for-profit that, among other things, collects licensing fees for reusing copyright materials, which it then distributes to copyright holders.

But copyright law is dry and the only sources were court documents and transcripts. I needed something to inject some of Frank’s own personality into the proceedings.

In the 1990s, Frank gave various talks about the case. One anecdote Frank told was about how one day he was reading a book about copyright, while sunbathing naked with a woman friend in the backyard at his Ewenton Street studio, when suddenly his heart started pounding:

I said to My Friend, there in the garden – “my god, intellectual property is about the very nature of existence. Intellectual property is the key to all understanding”.

He then explains three approaches to intellectual property – in terms of collective rights, moral rights, and economic rights.

One could be forgiven for placing this anecdote in late 1973 or early 1974. Frank explicitly places it as occurring “one day around the time of Moorhouse v University of NSW”.

But the problem is, in another version of the anecdote, Frank names the book he was reading that day: Copyright in International Relations by M.M. Boguslavsky. This book was published in Australia by the Copyright Council, edited by David Catterns, in 1979 – six years after the start of the copyright case, four years after the High Court’s final judgement in August 1975.

Maybe Frank got the book wrong? Perhaps. But this forced a closer look at 1979. I found a reference in October to a woman friend sunbathing nude at Ewenton Street. The following month Frank attended a symposium, hosted by the Copyright Council, on the question of moral rights. The speakers were Peter Banki and David Catterns. Frank was given a copy of their talks beforehand – with, or without, the Boguslavsky book.

Frank’s reference to moral rights and the expansive claim that “Intellectual property is the key to all understanding” is more consistent with that 1979 event than with the copyright case from years earlier. That case was deliberately narrowed down to the single legal question of “authorisation”.

And so, on balance, that anecdote does not hold, at least not as a point of entry into the 1973–74 copyright case. I omitted it from the biography, on the grounds that when the legend conflicts with the facts – print the facts, even when they are dry.

‘I find it impossible to remember’

We are all unreliable narrators of our own lives. Faulty memory and self-deception inflict us all when reflecting on our past. Frank is no exception; statements about his own life should not be taken at face value. This unreliability should be taken into account when weighing such statements.

Perhaps this is enough to account for the errors regarding these two stated moments? Frank himself suggests an additional explanation.

Writers of literary fiction often draw on actual experiences as a starting point for their work, which becomes – filtered through imagination, literary convention and narrative necessity – something very different from that initial experience. Frank had been writing since he was 12 years old, but as he got older he became aware of a peculiar psychological effect: the act of writing fiction distorted his memory in a particular way.

“By incorporating one incident and processing it into fiction I find it impossible to remember how that incident occurred in reality,” he wrote to a friend in 1967. “I have difficulty in remembering now what incidents occurred in my life and what occurred in stories.”

Two years later, aged only 30, he told an adult education class that one of the “losses” a writer “suffers” is the actual “incidents” of one’s own life:

he loses the accurate memory of how it actually happened once he uses, however loosely, a mood or an incident or a character – the created incident, mood or character is not simply confused by the fiction it is in fact replaced by the fiction.

Could this process also have occurred in balancing “the historical element” of his own life with the “the narrative element” in recounting that life? There are many examples which suggest so. Moreover, as with this distortion of memory when writing fiction, Frank is aware of this process occurring when telling his own life story.

During an address in 1997 – where he first relates the anecdote about nude sunbaking and copyright – Frank opens by outlining his first meeting with David Catterns and Peter Banki. “I see it occurring in the famous Marble Bar where Henry Lawson once drank,” he said. But did it occur in the Marble Bar?

In 1989, Frank gave an earlier talk about the Copyright Agency Ltd, titled: “How CAL got started in the Marble Bar”. There are two versions in the archives.

In the first version, where Catterns and Banki are referred to by their initials, Frank writes: “My first serious meeting with DC and PB was one day back in 1974 in the famous Marble Bar where Henry Lawson once drank.” In the second draft Frank keeps this sentence, putting their names in full, but adding in parenthesis: “I say Marble Bar because meetings did occur there, but it is a metaphorical site to dramatise the compression of many conversations over many months in many places.”

Frank admits he does not remember where that first meeting took place, and so he creates a legend which, after being repeated enough times becomes considered as fact.

Likewise, the legend of the 1975 Opera House rally was consecrated in 2005 in a book published by Melbourne University Press, titled: The Dismissal: Where were you on November 11, 1975?. Frank wrote one of the pieces, relating how that day he was at lunch with Donald Horne in the staff club at the University of New South Wales when news came in over the radio.

Frank segues into the legend of the rally: “In the following weeks, although I supported no political party, I was invited to speak at a great rally of support for Whitlam at the Sydney Opera House…” He repeats the story from Days of Wine and Rage, including falling asleep at the Journalists’ Club after.

But even here, Frank seems to be aware of the vagaries of memory and narrative, even as he applies this selectively. In a footnote to this 2005 piece, Frank adds a proviso: “Donald and I have different recollections of who was at this lunch. Never trust oral history.”

And never trust the legend.

Jaded with journalism

There is a further biographical thread that complicates this matter: a question of intellectual honesty and Frank’s relationship with the media. After graduating from high school, Frank started working as a copy boy, quickly becoming a cadet, then a journalist.

Before he was 21, he was editing a newspaper in Lockhart, New South Wales. He worked off and on as a journalist: for the ABC in the 1960s, The Bulletin in the 1970s, freelance reporting since the 1980s. He maintained his membership of the Australian Journalists Association for decades – hence his falling asleep at the Journalists’ Club in 1974. But he was never entirely comfortable being a journalist. This was a day job, so he could pursue his own writing.

He became jaded with journalism very early on. As a cadet he argued with more seasoned journalists over their use of hyperbole in writing stories, or with their poor treatment of citizens on the court beat. Frank exercised an intellectual honesty that put him at odds with his professional cohort. As an editor in Lockhart, it also put him at odds with the rest of the township.

This was fuelled by Frank’s reading in the history, sociology and psychology of media communications, advertising and publishing industries. In the 1960s, at the Workers Educational Association, Frank developed several courses on these topics, while also writing various longform pieces for the Current Affairs Bulletin (for example, “Now Here is the News…”, 1969).

They were all critical of methods and practices of journalism, obfuscated by what he called “journalistic mystique”. Behind the claims of independence, objectivity and just-the-facts rhetoric were economic and ideological dependencies, partiality, subjective decision-making and simplistic narrative forms that forced the “facts” to fit some pre-determined morality tale.

These functioned in our culture, Frank argued in one course, the same way as fairy tales and folk stories.

But from 1969 on, following the publication of his first book, Futility and Other Animals, Frank’s relationship to the media shifted, from being a consumer, producer and critic of the news, to being a subject of the news. This only reinforced his previous criticisms.

The first thing that happened was the undermining of his literary fiction’s autonomy. The process of writing stories, where the facts of his experience were replaced by the fiction of his imagination, was collapsed by reviewers and journalists, with the resulting fiction being reported as autobiographical or documentary “fact”. Additional associations were then overlaid.

Perhaps the earliest was Frank’s association with the Sydney Push – that bohemian subculture that emerged out of the University of Sydney in the 1950s. The influence of the Push became overdetermined and was rarely questioned (consider the hastily written obituaries when Frank died in June 2022).

But many of the intellectual positions Frank held that were shared with the Push – advocating for freedom of expression, for sexual freedom, against censorship – were fully formed in him (and articulated) before he became involved with them.

Many of the short stories he wrote during the 1960s drew on experiences he had in the late 1950s, before he entered this circle. And on the rare occasion he did write about the Push (without naming it as such) – for example, “The American Poet’s Visit” (Southerly, 1968) – it is as satire. In 1963, he wrote a paper criticising this cohort as being “reactionary” and “conservative”.

This should not be overcorrected. The Push was part of the facts of Frank’s life, but only a peripheral part. He spent more time, for example, during the same period, at the Workers Educational Association, a role he found more intellectually fulfilling and politically relevant – but that was not reported on by the media.

Read more: Susan Varga's Hard Joy explores the possibilities and limits of memoir

‘Ironic involvement’

Frank’s association with the Push is best described by his own notion of “ironic involvement”, which he defined in the late 1960s as being “where the person participates in human endeavour but as both an observer and game player”. He explains:

Ironic involvement is a description of a relationship to activity. It may in fact, queerly enough, have some of the outward manifestations or appearances of commitment but the relationship beneath the behaviour is radically and fundamentally different. Contained in the ironic attitude is an almost constant awareness of the briefness and insignificance of life, the absence of sacredness, the futility of effort, the paradoxical, the hypercritical, the betrayals, the pretensions, the deceit, the self-deceit, the mutual exploitation and the cruel and bewildering nature of the human condition.

This also describes Frank’s engagement with the media. He became a media game-player, the public persona, “Frank Moorhouse, writer”. This revealed itself in interviews and in news reports on various activities he was involved in.

There is an important caveat to Frank’s “ironic involvement” with the media, however: his intellectual honesty meant he tried to be as accurate as possible when it came to speaking about broader issues and events, and other people.

It was only when talking about himself, his private life and his past that he was a media game-player: sometimes truthful, sometimes not, sometimes telling an anecdote while suggesting it may not be necessarily so.

Frank used hyperbole and distraction in his personal public statements – the cumulative effect of which is the outline of his public legend – in part to protect himself, to cover his trauma and anxiety. And in part he did it to compartmentalise his life, to negotiate the relationship with his family and distinct groups of friends, lovers and acquaintances. To hide from the public, while in public. This was particularly the case regarding his sexuality and gender identity, and the personal difficulties relating to each.

There is a chronological aspect to this: something he would keep to himself at one stage of his life would be slowly revealed over time, in various guises or to various degrees of disclosure. At each moment, Frank would use his understanding of the media to position himself within its coverage in a way that meant he could advocate for ideas he was interested in, while at the same time controlling how those ideas could be applied to himself.

The personal and political

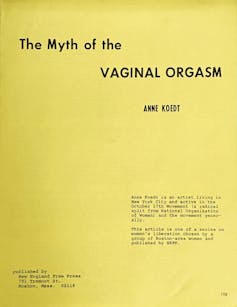

In 1971, for example, Frank wrote an essay responding to Anne Koedt’s 1970 pamphlet, “Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm”. There are three versions of the essay.

The shortest version, containing the core of his argument, was published in The Bulletin. This had a large mainstream audience – and, importantly, it was read by Frank’s family. This version reveals nothing of a personal nature, but still argues for a renegotiation between the sexes, and for a social openness in talking about sexual pleasure and anxieties.

A longer version was published in Thor, an underground student newspaper, circulating among Sydney bohemia. Here Frank admitted – for the first time in a public forum – that he had homosexual relations. But Thor had a smaller, less mainstream, more sympathetic audience. Frank could risk revealing part of himself.

There is a final version, however, that touches more on the confusions of Frank’s gender identity – and this remained unpublished. This was something Frank was not yet ready to disclose socially, even within his own subculture.

In Days of Wine and Rage, Frank reprinted the Thor version, including his personal admissions. But by the mid-1980s he downplayed even this, telling interviewers he had “homosexual streams” in his life, but in the past – when, in reality, it was ever present. Around the same time, in an unpublished interview with a university student, Frank first disclosed his transvestism.

This chronological aspect is also where biography intersects with social history. These prevarications and feints are part of Frank’s negotiation of shifting social conventions and historical moments, from a period when homosexuality was legally prosecuted and socially persecuted, through to a period when homosexuality was decriminalised.

This began federally in 1973, and continued state by state, from South Australia becoming the first state to decriminalise homosexuality in 1975 until Tasmania became the last in 1997. The social opprobrium slowly shifted, but never entirely lifted. This becomes an active ground on which Frank’s biography unfolds.

In the late 1950s, for example, Frank was a court reporter in Sydney, during a period when the number of arrests and prosecutions in New South Wales was on the rise. His comments on his sexuality in the 1980s were made against the background of a developing HIV/AIDS crisis. In between, in 1964 – seven years before his first public admission regarding homosexuality – a 24-year-old Frank said in a lecture:

There seems to be a large minority engaged in the exploration of sexual relationships outside of the conventions. But the interesting point is that this exploration and its results are being concealed by many of these people. Where this concealment occurs among people who are concerned with freedom of action, freedom of information, and the creation of an open society, then they can be criticised. But I want to be gentle in my criticism because I realise that there are immense personal problems in becoming a sexual radical. The obvious case of extreme difficulty is the homosexual. If he behaves openly he will be persecuted and gaoled.

Decades later, Frank gave his younger self greater sexual awareness, self-confidence, and agency. In his 2005 memoir, Martini, Frank recalls how, around the time of his 18th birthday, he began a sexual relationship with an older man. “I had seduced him,” Frank wrote of their first encounter.

It was a point he kept repeating to me, in conversation and correspondence, whenever we discussed this situation: Frank seduced him. But the contemporaneous evidence suggests otherwise, and records Frank’s initial response as being freighted with guilt, disgust and repulsion; his internalising of what in the years to come he would refer to as “a sexually sick society”, one that imposed a narrow conventional morality over its citizens.

Accepting the legend would mean omitting the arduous process by which Frank dealt with his own “immense personal problems in becoming a sexual radical”. The personal denial, confusion and acceptance, and the public denials, obfuscations and tolerance, are necessary parts of the facts of his life.

As much as literary biography intersects with social history, it also intersects with political history. In the introduction to The Dismissal, for example, Jenny Hocking, Whitlam’s biographer, points out that the 1974 federal election has been “ignored and invisible in contemporary reference”, distorting our collective political memory.

She cites Whitlam referring to his second-term win as “the election that never was”. Frank’s misremembering of the Opera House rally that accompanied that election reinforces that broader political amnesia and misunderstanding.

Such seemingly trivial moments – when a particular political rally occurred, or where a meeting took place, or an incident occurred – can have broader ramifications. A biography is constituted by numerous moments such as these, intersecting various larger histories - and that is where its responsibilities lie.

Putting the legend in its place

The line from Frank’s 1975 Wollongong talk is a variation of a line from the 1962 Western film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (directed by John Ford). The James Stewart character had built a political career on the legend that he shot the outlaw Liberty Valance (played by Lee Marvin), even though Valance was actually shot by the John Wayne character. When James Stewart comes clean to a newspaper editor about the story, it is the editor who finally burns the confession, stating: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

We cannot infer from Frank’s notes what interpretation he gave the line that day in 1975: whether he approved of it, disapproved of it, or whether he used it ironically. But this John Ford film is a dramatic example of what Frank had spent more than 15 years at that point arguing against in public culture.

When I first reconsidered these two moments – the legends of the Opera House rally, and the backyard copyright revelation – I realised I had fallen into the trap at the heart of Frank’s media and cultural criticism.

With my initial outline, pieced together from public sources, I was doing what Frank himself objected to in the methods and procedures of a journalist in making those public sources. I was making the “facts” fit some pre-determined narrative, papering over anything that would contradict the legend. Perhaps, too, I was leaning too heavily on my personal relationship with Frank – but knowing him as a friend is not the same as understanding him as a biographical subject.

These moments forced me to start the project over. I abandoned my initial outline and chapter breakdown, expanding the scope of the project and obliterating my initial writing schedule – with frequent apologies to my publisher.

I put public sources and statements by Frank himself at a critical remove, and went back to the archive, not as a retrospective response to various calls my preconceptions were asking of it, but to provide the set of questions I needed to slowly, gradually find provisional answers for, through a steady, chronological building up of material.

This time the project opened up in far broader and more interesting ways than I had previously considered. It led to the discovery of material previously missed or otherwise unavailable to either the archive or the public record. But this new method also meant making certain omissions, killing other darlings, putting the legend in its place. It required weighing the material according to the vagaries of fact and fiction, memory and deception (including self-deception), intentional or otherwise.

Biography is about making an argument for a particular account of a person’s life and times, while acknowledging the limitations of doing so, and the doubts inherent in the attempt.

In the conflict between the facts and the legend, the question became not only how to establish the facts, or disentangling fact from legend, but a more interesting and important question: how did the legend of “Frank Moorhouse” develop? And how to incorporate this development into the facts of his life – particularly those facts the legend kept hidden?

Wrestling with this question, I would argue, brings us closer to understanding Frank than if I had focused on just the facts, or just the legend. It also brings us closer to understanding ourselves, and a culture Frank Moorhouse himself felt the need to alternately challenge and hide from, all while producing an extraordinary body of work.

Matthew Lamb’s biography, Frank Moorhouse: Strange Paths (Knopf Australia) will be published on November 28 2023.

Matthew Lamb does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.